ARMIN ROSEN

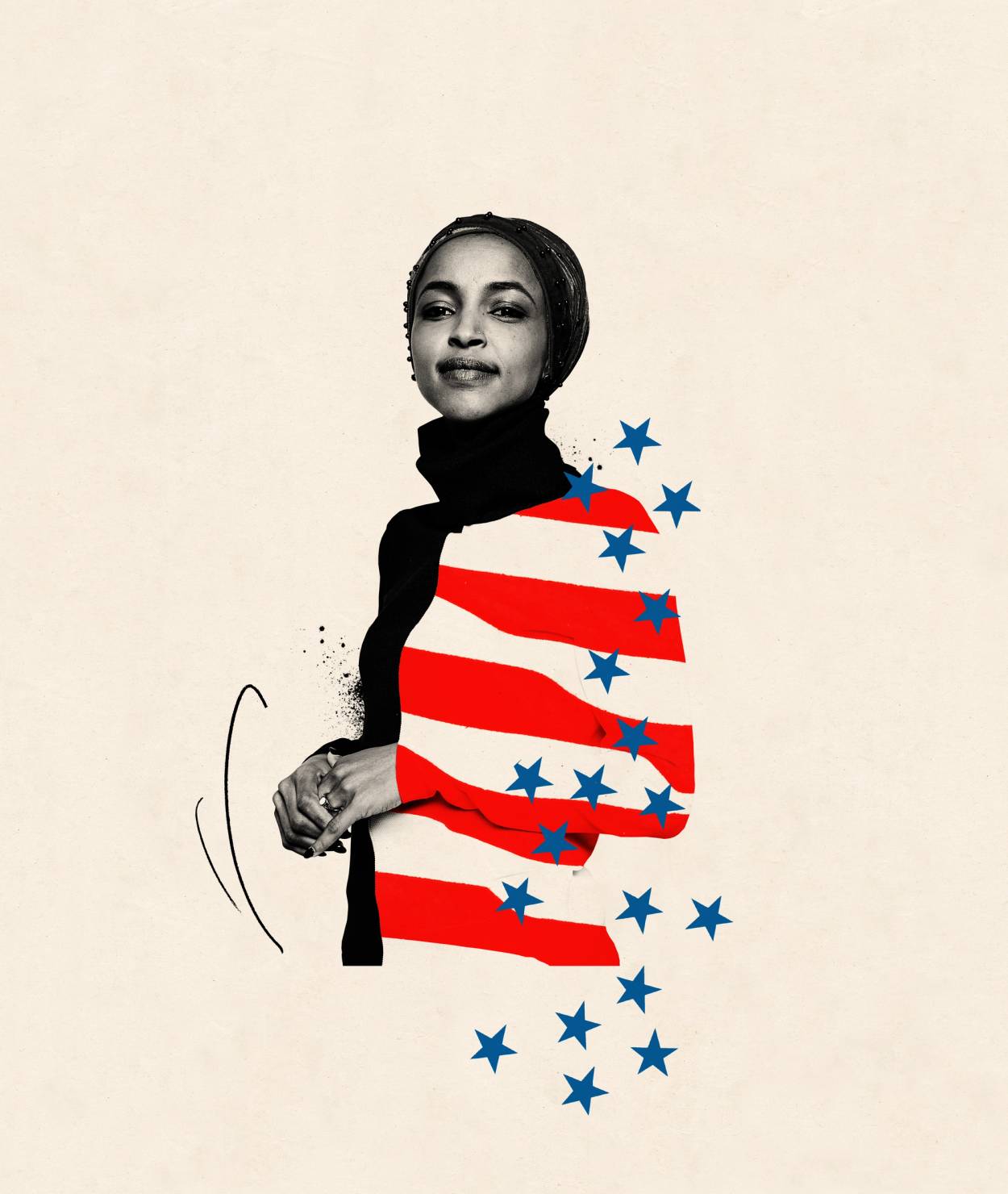

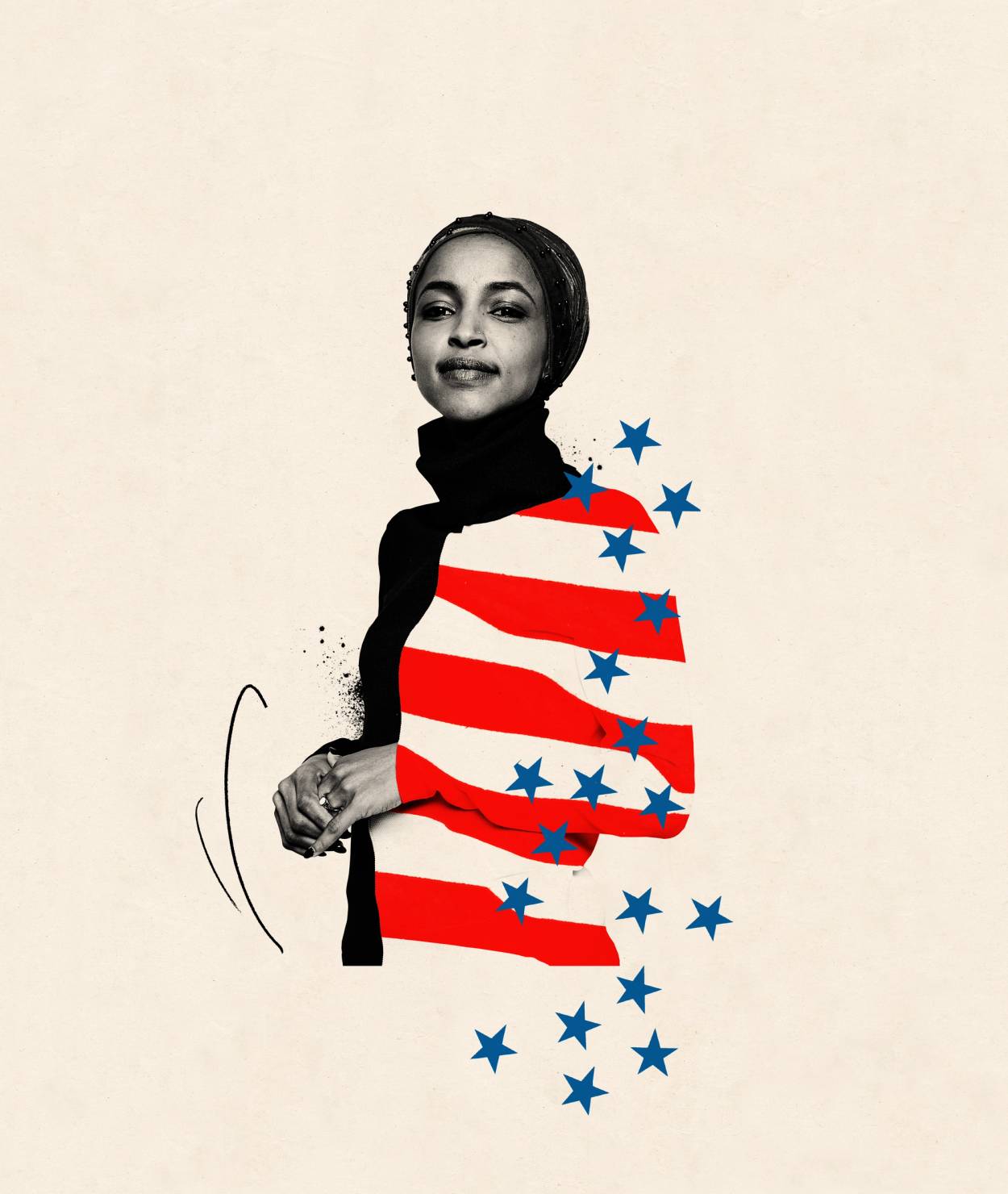

Traveling through East Africa and Minnesota reveals a story more quintessentially American than either the congresswoman or her detractors want to admit.

.

CRISTIANA COUCEIRO

CRISTIANA COUCEIRO

On July 2, 2022, Ilhan Omar briefly appeared onstage with Suldaan Seeraar, a Somali pop star making his U.S. debut. It was the first time the sizable Minneapolis Somali American community had held an event at the Target Center, the arena that’s home to the Twin Cities’ NBA team. Like Omar’s political career, the concert marked the power and permanence of a relatively new community of Americans, one that barely existed just 30 years earlier. Presented before thousands of young Somalis, many of whom had come from Columbus, San Diego, and other centers of Somali American life, Omar, the world’s best-known person of Somali ethnicity and one of the only members of the U.S. House of Representatives who is a bona fide national figure, faced a torrent of booing. The jeering accelerated as she began to address the crowd. “We don’t have all night,” she chided with a wide and unembarrassed smile across her face, as if the congresswoman was reveling in the open scorn.

That Omar is unpopular among some Somalis should not be surprising by now. Her primary campaign for the Minnesota state legislature in 2016 pitted her against a former Somali American political ally, Mohamud Noor, as well as against Phyllis Khan, an incumbent supported by Minneapolis City Councilman Hassan Warsame, then the Somali community’s leading elected politician. Omar defeated them both. Her supposedly heroic opposition to the religious and social conservatives of her own community was a major theme of This Is What America Looks Like: My Journey from Refugee to Congresswoman, Omar’s May 2020 memoir. From the beginning of her political career, her views on abortion, homosexuality, and a range of other topics were not those of a staunch Muslim traditionalist, and were even to the left of what a standard-issue Minnesotan typically believed. At the Target Center, she brought onstage her husband Tim Mynett, a political consultant who is not Somali and only converted to Islam around the time he ended his previous marriage and married Omar. Ahmed Hirsi, Omar’s previous spouse, was a well-known and once relatively popular figure in Twin Cities Somali affairs.

Perhaps, one source in the Minneapolis Somali community suggested to me, the booing expressed the growing edginess of a younger generation that was more open to taking a hard line on matters of religion and morality than even their parents had been. The Somali American community has produced plenty of young people vocally committed to progressive politics—the booers didn’t seem to represent a majority of the Target Center crowd, after all—but also many others who have gone sharply in the other direction, toward a religious fundamentalism that was itself a reaction to distinctly American realities. It could all be very bewildering, including to Somali Americans themselves. “Our children, they look like us,” said the man, a political strategist and activist in south Minneapolis, “but they are not Somali. They are American.”

Omar didn’t get to where she is by reconciling any of these contradictions but by making them work to her advantage. For most politicians, it would be a humiliating rebuke to have thousands of members of their ethnic and religious community rain boos upon them at a major public event held on their home turf. The smiles and laughter with which she greeted the opprobrium of young Somalis didn’t come from nervousness or surprise. This was the kind of confrontation that had helped turn her into a political star.

Omar’s instincts are rarely wrong, however polarizing a figure they’ve made her. In 2020, she ran 16 points behind Joe Biden, underperforming the president-elect by more than every one of the other 200-plus Democratic members of the House of Representatives up for reelection. But she still won 64% of the vote on the strength of a firm base of support that included far-left activists, college students, left-wing children of culturally conservative Somali immigrants, and the social-justice-minded bourgeois, newly activated by the protests and riots that broke out after the killing of George Floyd, which occurred in Omar’s congressional district. The Target Center incident might have looked like an ugly scene to people who knew little about her life and career, or like an opportunity for political opponents wrongly convinced that she’s beatable this year. Omar is up against former city council member Don Samuels in August’s Democratic primary, an unexciting alternative from an earlier political era who is likely headed for the same double-digit defeat that an earlier and even more promising challenger suffered in 2020. It’s unclear that any attack on Omar has ever landed particularly hard.

Being a lightning rod would have harmed Omar if she hadn’t proven to be such a skillful manager of her own story and her own image. That’s especially true when it comes to the more sensitive aspects of her dizzyingly complex life, which she has either ruthlessly neutralized, cleverly spun, or kept scrupulously out of view.

On June 15, 2020, Omar announced that her father had died of complications from the coronavirus. When Somalia plunged into its still-reverberating civil war in the early 1990s, Nur Said, then in his 30s, braved the spreading anarchy to make sure his children and extended family made it from Mogadishu to Kenya, and then from a refugee camp to final safety in the United States. Since he is someone who rescued his loved ones from a war zone and raised a pathbreaking contemporary political figure, it is a permanently lost opportunity that Nur Said never seems to have recorded his life story in any public form, or given a single media interview of any real depth. His contribution to his daughter’s astonishing political rise remained vague until the very end. In Time for Ilhan, a 2018 documentary about Omar’s victorious 2016 campaign for the Minnesota state legislature, Nur Said is shown eating lunch and talking in Somali with Omar, hanging around rallies and polling places with other older Somali men, and accompanying her to an election-night victory party. When he speaks in Somali, his words are only rarely translated. He is introduced in Time for Ilhan as “Nur Said,” though Omar named him as Nur Omar Muhammed Omar in her tweet announcing his death.

Rep. Ilhan Omar’s father, Nur Said, center, at the swearing-in ceremony at the start of the 116th Congress, U.S. Capitol, Washington, D.C., Jan. 3, 2019SAUL LOEB/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

Rep. Ilhan Omar’s father, Nur Said, center, at the swearing-in ceremony at the start of the 116th Congress, U.S. Capitol, Washington, D.C., Jan. 3, 2019SAUL LOEB/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

Omar’s father is one of the heroes of her memoir. Yet she offers scant details about his life in the old country, in contrast to other family members. For instance, we learn that Omar’s maternal grandfather held “a government job, helping to run the country’s network of lighthouses.” He was also an accomplished Italian gourmand, Italy being Somalia’s former colonial ruler. In 2016, Omar told the Minneapolis alternative newspaper City Pages that her grandfather had been Somalia’s “national marine transport director” and had gone to college in Italy, although neither detail appears in her book.

Omar’s memoir does mention the “unusual privileges” that the future congresswoman’s mother, who died during Omar’s infancy, had been “afforded by her father,” Omar’s politically connected grandfather. The family compound in the Somali capital, which belonged to Omar’s mother’s side, was behind a protective wall and filled with books, music, and art. The family owned its own car, a Toyota Corolla, something also unusual for subjects of an impoverished communist dictatorship. Readers don’t learn about Nur Said’s prewar life or social status at the same level of specificity, aside from finding out that he grew up in one of the major towns of the Puntland region, northeast of Mogadishu, and belonged to a subclan that the regime of Siad Barre had once persecuted. He is twice referred to as an “educator,” with no further detail given.

This lingering gray zone would not be filled in until after Nur Said’s death. In a Somali-language condolence tweet, Omar Sharmarke, who served as Somalia’s prime minister from 2009 to 2010 and then again from 2014 to 2017, described Nur Said as “Col Nur”—that is, as a colonel—and noted his service in Somalia’s armed forces. Sharmarke is a former Somali ambassador to the United States who speaks fluent English; his father, a president of Somalia, was assassinated shortly before Siad Barre’s coup in 1969. Within the Somali clan system, he belongs to the same sub-sub-sub-clan as Nur Said and Omar.

During the six months before Nur Said’s death, over a half-dozen Somali Americans in the Twin Cities and Virginia—among them a former post-civil war Somali government official, the son of a general who had served just before the civil war, and multiple people close to either Omar or her ex-husband Ahmed Hirsi’s family—told me that Nur Said had not been an “educator” but a mid-ranking professional officer in the Somali military during Barre’s regime. Public messages from Sharmarke, as well as from Somali community members in Minnesota, presented additional proof that Nur Said once held rank in a military that was notorious for torturing political prisoners, bombarding the country’s own cities, and persecuting clans deemed disloyal to Siad Barre’s ruling clique. Minnesota Public Radio-affiliated website Sahan Journal eventually described Nur Said as “a prominent Somali military officer.”

For Omar and other Somali refugees, life in the United States offered the possibility of a complete break with the war, and with the decades of accelerating national breakdown that made the conflict possible. In America, Somalis were free to recreate some of what they’d had in East Africa, in a country where a societywide self-immolation was at that point unthinkable. Religious and social life, including aspects of the Somali clan system, quickly reasserted themselves in places like Minneapolis. This diasporic revival was only possible because of a shared impulse toward leaving the worst of the civil war in the country they’d escaped. At almost no point have Minnesota’s Somali Americans ever accused one another of decades-old crimes back in East Africa. “There’s this kind of a collective social attitude: Whatever the hell happened, we left it in Somalia,” explained Ahmed Yusuf, a Minneapolis high school teacher and author of the book Somalis in Minnesota.

As an immigrant, a racial and religious minority, and a survivor of war, Omar had a tougher path to Congress than fellow “squad” member Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, or nearly anyone else for that matter. But navigating Somali politics in both the Twin Cities and the Horn of Africa gave Omar a head start in understanding what it would take to make it in a fracturing near-future America. The Minneapolis Somali community, recent Somali history, and Omar’s own personal history turned out to be perfect preparation for a consequential political career in an ever more divided United States.

Conveniently for Omar, the only people who have seriously investigated her past during her now 6-year-old career in electoral politics are writers for right-wing websites. Fringier media have accused Nur Said of being a war criminal or the commandant of a prison camp, stories that have not been persuasively supported and that reflect a mix of conjecture and rumors circulating within the Twin Cities Somali community. These insinuations allow Omar’s critics to present her as having personally benefited from human rights atrocities, only to then appoint herself an uncompromising accuser of her adopted country’s injustices once she entered politics.

Holistic treatments of her life and career are largely absent in mainstream or nonideological outlets. The few that have been written are built around narrow biographical questions or seem to be almost entirely based on Omar’s own statements, which most publications haven’t bothered to check or challenge.

In 2019, the year the newly elected congresswoman became a household name, the closest a major national publication came to a full profile of Omar was a July piece in The Washington Post. The article noted a number of factual misstatements she had made—she told a veterans’ group that 45% of military families were on food stamps, which was nine times greater than the actual number. She told a group of high school students that she had once watched a “sweet, old African American lady” sentenced to a weekend in jail and an unpayable fine for stealing a $2 loaf of bread.

The Post allowed for the possibility that the incident, for which there was no evidence but Omar’s recollections, had been made up on the spot. “If true, it is also probably embellished,” the newspaper determined, adding Omar “said she may have flubbed some facts.” No matter: The story was undeniably powerful. Omar probably already understood that its truth was immaterial, and that the risks of getting caught in the fabrication were worth the payoff. Much of the article was dedicated to soft-focus accounts of congressional busywork and interviews with Minnesotans who had nothing critical to say about her.

That Omar could secure such light treatment from an outlet as powerful as the Post further confirms her mastery of the modern-day political media ecosystem. But such mild scrutiny also does a disservice to Omar, who is often reduced to a series of cliches—whether as a vindication of liberal immigration policy, or evidence of the country’s inevitable march leftward, or an affirmation of America itself, with its ability to make winners out of people the crueler regions of the world had victimized. The press’s evident lack of curiosity about Omar also smacks of self-regard: Dissecting Omar’s life story is seen as a right-wing pastime. An absence of interest in her biography, and even in her pre-congressional political career, serve as proof of being enlightened enough not to belong to the wrong club.

Aided by the media’s tactical retreat, Omar has become the public’s first and final source for understanding how one of the country’s major political figures got to where she is. She has ensured that certain aspects of her life—like her father’s services to the Siad Barre regime, along with everything it suggested about how and why Omar was able to escape a collapsed state and then succeed in a country thousands of miles from her troubled birthplace—are mentioned only by her opponents. With the help of dedicated supporters, an incurious media, and the racial and religious antagonism of Donald Trump, Omar succeeded in streamlining her labyrinthine history into a stirring tale of an indomitable spirit achieving its destiny, demolishing American backwardness in the process.

Omar has now been in Congress for over three and a half years. American politics has lost much of its local and even regional character, thanks in part to figures like her. The country’s political life is now almost entirely national-scale and personality-driven, a clash between controversy-seekers who are essentially celebrities, and who are constantly vying for attention and adoration before a third of a billion citizens. Omar recognized this shift to a world of Ocasio-Cortezes and Marjorie Taylor Greenes earlier than nearly anyone. She understood that she was playing on a field larger than a single state assembly or congressional district, or even any single country. She realized that politics was becoming an arena defined less by policy and action than by narrative and personal emotional investment. Proceeding from this insight, she became a lone voice willing to stake out provocative or maximalist positions that some growing portion of the country wanted to hear: on Israel, on race relations, on student loan forgiveness, on the integrity and inner motives of her own Democratic Party colleagues.

American politics has risen—or perhaps fallen—to meet Omar’s level of stridency. The upheavals of the post-George Floyd moment, the coronavirus pandemic, and the chaotic aftermath of the 2020 presidential election accelerated an existing process: The realignment of the country into durable and often impenetrable enclaves of competing narratives, each convinced that the American project is under existential threat from nearly everyone outside of their own camp, whether those enemies are Trumpists, QAnoners, white supremacists, cops, Zionists, COVID-truthers, neoliberal capitalists, anti-vaxxers, the trans movement, Black Lives Matter, critical race theorists, police abolitionists, democratic socialists, or the professional managerial class. The other side is often believed to be guilty of evils so appalling that even attempting to win them over to your side, rather than forging ahead to isolate and destroy them, is seen as self-betrayal.

American politics now resembles a tribal struggle, a competition between a constellation of in-groups over scarce resources and even scarcer channels of actual power. Protecting and advancing one’s political tribe using the full range of available tools, including media manipulation, calculated dishonesty, and mass protest, is often an objective that supersedes any loyalty to a political party or ideological system, as well as to any higher ideals, like the truth.

One example of Omar’s command over this ascendent mode of politics was her blockbuster tweet of April 16, 2022, in which she shared a video of a group of Christians singing a religious song in the middle of a packed flight. The only hijab-wearing congresswoman in American history spoke up to stigmatize this public display of religiosity, which she saw as proof of the bigotry of the country in whose national legislature she serves. “I think my family and I should have a prayer session next time I am on a plane,” she quipped. “How do you think it will end?” The people in the video were completely anonymous, lacking Omar’s profile and power. They had no connection to Omar’s district in Minneapolis, or to any question of policy, major or minor. But Omar recognized that the video was a chance to teach certain Americans about how awful they are, and to amplify a grievance so forcefully that any further debate would be less pithy, less interesting, and less instantly divisive than Omar’s initial shot. Her name trended on Twitter for two days. The tweet generated op-eds and news segments and currently has over 200,000 likes.

Ilhan Omar’s story is the journey of Somalis and other vulnerable populations that found safety in contemporary America, in part by gaining the freedom to choose what to take with them and what of their old lives to leave behind.

Omar’s attention-grabbing and divisive political theater serves her purposes even when it verges into absurdity. On July 19, police escorted the congresswoman off the grounds of the Supreme Court during a pro-abortion rights protest. Along with Ocasio-Cortez, Omar held her hands behind her back, creating the false impression she had been handcuffed. The ruse worked: ABC News, among others, tweeted to announce the arrest of the two legislative stars. Whether or not corrections are on their way, the image of Omar half-grinning behind thick sunglasses, wearing a necklace whose dark amber beads matched her shirt and hijab, with a cop appearing to restrain her and the high court’s Corinthian facade looming in the background, has a power far exceeding that of whatever the bare facts might be.

Ilhan Omar’s emergence as one of the era’s defining political figures, and the likely longevity of her congressional career, make it all the more important to understand how and why she got this far. Her story, and its fateful intersection with both Somalia’s and America’s modern history, are reassuring proof that the United States remains a land of reinvention. For Somali refugees, as for Jews a century earlier, America was an escape hatch from history, the only place on Earth where a painful recent past could be peacefully reconciled. Ilhan Omar’s story is the journey of Somalis and other vulnerable populations that found safety in contemporary America, in part by gaining the freedom to choose what to take with them and what of their old lives to leave behind. Omar, like centuries of ambitious newcomers to America, fully inhabited the freedom to transform into whatever she imagined herself to be.

lhan Omar was born in Mogadishu in 1982. Her mother was from a Somali clan that traces its origins to Yemen; she died when the future congresswoman was still a baby. In a poignant scene in Time for Ilhan, the state legislature candidate reflects on her mother’s absence as she braids her youngest daughter’s hair. “When I was little like you, my sisters would cut off my hair and make me bald all the time. You know why? Because I didn’t have a mommy, and nobody had the patience to do this crazy business.” Her father was from the Osman Mahmoud subclan of the Majeerteen branch of the Darod. Clan is patrilineal in Somalia, so Omar and her siblings are also considered part of the Osman Mahmoud, a grouping that traces its descent from a line of medieval sultans. “Like me, she comes from a royal family,” Haji Mohamed Yasin, a Nairobi-based analyst and political activist, explained when I met him in Kenya in the fall of 2019.

The young Omar lived in a safety and comfort unimaginable to nearly everyone in what was largely a very poor country. Per Omar’s memoir, her mother had been a “secretary for a government minister,” while her paternal grandfather was the government maritime administrator with a talent for Italian cooking. Omar writes that her “family of civil servants and teachers was well off enough to have a guarded compound and driver. But I didn’t like the attention I received from the other kids for the in-your-face privilege of our white Toyota Corolla and our driver Farah—nor the constraints.”

It is not in itself morally compromising to have acquired wealth and safety in Barre-era Somalia, as Omar’s family had. “In the case of Ilhan Omar and her family, they’ve been privileged from the get-go, before the establishment of the Somali state,” said Adam Matan of the London-based Anti-Tribalism Movement in late 2019, speaking to a general perception among diaspora Somalis of Omar’s origins. “She was in Mogadishu, part of the well-off people in Somalia. Then literally out of nowhere, you have to flee for your life.”

Nearly every path to bourgeois comfort and the kind of multigenerational, multibuilding family compound that Omar describes in recollections of her early life in Mogadishu ran through Siad Barre’s regime. Beginning in the 1970s, the authoritarian dictator had put the country on a glide path to catastrophe.

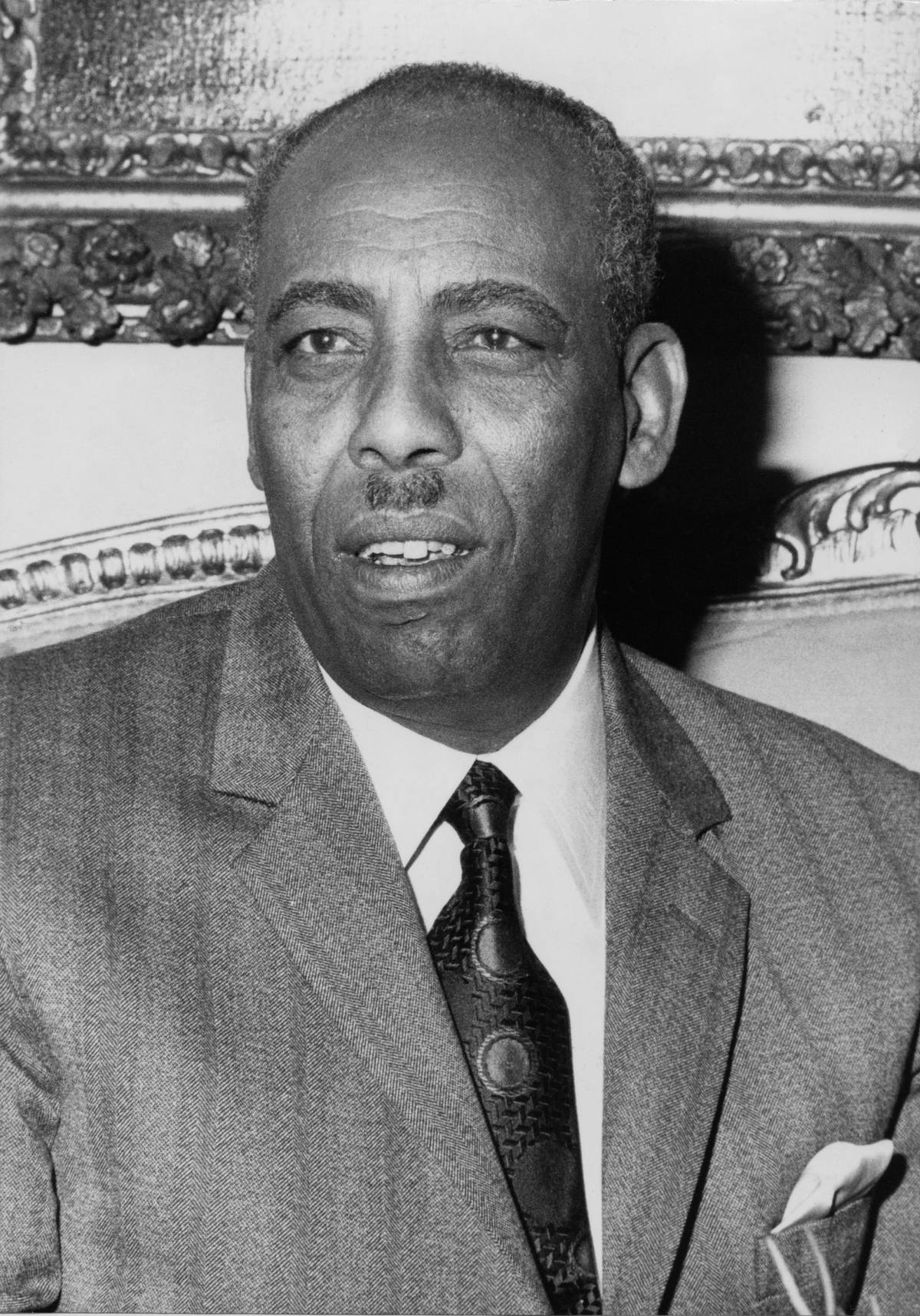

Barre gained power in a 1969 military coup, ending the nine-year democratic experiment that followed Somali independence from Italy. He was known as “the Old Man,” a stoic and distant figure who surrounded himself with younger military officers he could control. Many dictators are lazy or stupid, and rule on nothing more complicated than fear, but Barre had a reputation as a cerebral workaholic who would stay in the office until the early morning hours. “Barre was an extremely shrewd dictator,” said Ali Abdullahi, a Nairobi-based scholar, when I met him in 2019. “He knew his friends and foes really well. He mastered the art of clan dynamics.”

Siad Barre in 1976KEYSTONE/HULTON ARCHIVE/GETTY IMAGES

Ruling as a communist revolutionary, Barre sought to impose an alien ideology on a society of herders, farmers, oral poets, and traders bound together by family, religion, and various other sources of meaning and cohesion that communism sought to anathematize. Though he counted a widely praised literacy push among his successes, Barre’s rule was never secure. Ruling over a Soviet client state made him into a minor enemy of the United States. Internally, he was up against forces far older and more respected than any single dictator or political ideology, Islam high among them. One of Barre’s first major atrocities was the 1975 execution of 11 religious leaders accused of preaching against the regime’s “women’s emancipation” campaign.

By 1977, Barre’s attempts to impose socialism had cratered the country’s agricultural and industrial production. The dictator launched the most reckless gambit of his time in power and invaded the Somali-majority regions of eastern Ethiopia, which he hoped to annex. The campaign failed when the Soviet Union switched sides in the conflict and started backing the brutal communist regime of Ethiopian junta leader Mengistu Haile Mariam, which repelled Barre’s expedition into the Ogaden region with the help of Soviet weapons and military advisers, as well as 12,000 Cuban commandos. The humiliating defeat left Barre with one possible path to survival: The exploitation of Somalia’s clan system, which, like Islam, was a rival to communism entirely organic to Somali society.

Clan acts as a framework for the current Somali political system. At the 2001 Djibouti peace conference, negotiators arrived upon an idea known as “4.5,” in which one member from each of the four largest clans must fill exactly one of the highest offices in the government, with the “point five” referring to a representative of one of the so-called “minority” clans. Today, Somali politicians frequently travel to Minnesota to fundraise among fellow clan members.

The organization of the Somali political system along genealogical lines—or the perceived lack of any clear, nonviolent alternative to such a method of organization—is less absurd in light of everything that clan encompasses beyond electoral politics. In the most ethnically, linguistically, and religiously homogeneous place in Africa, clan remains the identity of both first and last resort. “For some, the clan has always been a kind of insurance,” explained Abdirahman Abtidon, a Somali-language author and a research collaborator at the University of Rome’s Somali Studies Center. “If some group attacks, who defends you? Your family.” During periods of clear centralized authority, like Barre’s rule, clans provided ready-made channels of loyalty. During periods of no authority, the clan was one of the last social institutions that endured. “Somalis survived the civil war because they had other constitutions, not just written ones,” Abtidon said.

One of Barre’s first atrocities in remaking the clan system to suit his political ends was his persecution of the Majeerteen subclan of the Darod, whom he scapegoated for the Ogaden disaster. Barre belonged to the Marehan, a different branch of the Darod. In 1978, his regime executed 17 Majeerteen officers accused of plotting a coup, and then launched a broader campaign of persecution. “Hundreds of military officers were rounded up, the civil service was purged, and political leaders, elders, intellectuals, businessmen, religious leaders, even women were sent to Barre’s worst prisons,” historian Lidwien Kapteijns writes in her 2012 book Clan Cleansing in Somalia. Outside this social and political elite, the regime burned 18 Majeerteen villages, massacring an estimated 2,000 people, seizing cattle, and planting mines under agricultural lands. The purge fractured the Majeerteen elite. Some left Somalia to join various opposition movements in exile. Other Majeerteen stuck around, including Omar’s father.

Serving the Barre regime as a Majeerteen did not make Nur Said a target of suspicion among Somalis in Minneapolis. He was widely respected and remained active in Somali affairs in the city. Omar made an effort to incorporate her father into her political campaigns; in a Facebook post, Sahra Noor, Omar’s older sister, described him as “a great political strategist and fundraiser.” In Omar’s memoir, she recalls her father interceding with Somali communal elders in Minnesota who had sworn to crush the progressive upstart’s state legislative campaign in 2016. Somali Americans in the Twin Cities say he was a frequent presence at the Starbucks in Cedar-Riverside, a gathering place for Majeerteen men. A Nur Said Mohamed Elmi appears as a signatory on an open letter from “Concerned Jubaland Communities” supporting the creation of an autonomous Jubaland state within Somalia’s fragile federal system. (Though Nur Said was from Puntland, both areas have large numbers of Darod; both are also in constant tension with the weak central government in Mogadishu.)

Nur Said was a member of “the older generation,” as one Somali community source in Minneapolis put it—someone who kept with people his age, and who usually only spoke in Somali. Another Minnesotan friendly with the family described him as “very mild-mannered guy, subdued almost. But very smart. He had this quiet wisdom about him. He also had something completely different from any Somali father I know. He had this kind of deference to his daughters … he wanted the attention for her, not for himself. You could sense it.”

Practically everyone in the Somali state apparatus had an intimate look into the country’s slow-motion collapse. Abdirashid Buule, who became a field worker for the Ministry of Livestock after graduating from high school, recalled that by the mid-1980s, his teams could no longer access certain areas unless they had the explicit permission of local clan militias. The government had its own preferred militant groups, which meant that local-level contests for authority were raging even before civil war broke out. “What we had was better than without a government,” Buule told me in Nairobi in 2019. “But the system was only for itself. Barre only thought of that day, when he had power.”

Defections of senior regime officials, including Barre’s ambassador to the United States, began in the early ’80s. Civil war erupted in 1987 when Barre’s air force flattened Hargeisa, the largest city in a region in which the Ishaq clan was dominant. The dictator had leaned on the clan system as his rule deteriorated, favoring the Marahan, Ogaden, and Dulbahante sub-clans of the Darod and killing thousands of Ishaq in order to terrorize the restive north of the country into submission.

From Nairobi to Melbourne to Minneapolis, much of the Somali diaspora traces its creation to the final weeks of 1990, when rebels reached Mogadishu and the country descended into a chaos from which it is yet to fully emerge. Mohamed Farah Aidid’s United Somali Congress entered the city, kicking off months of reprisal killings targeting any member of any branch of Barre’s Darod clan, regardless of whether they supported the regime. “All those associated with ‘the’ Darod—a genealogical construct that encompassed a score of clans and a large percentage of the inhabitants of Mogadishu and the country as a whole—now, irrespective of their individual histories, came to be seen as enemies to be killed and driven out,” Kapteijns writes. In its first year, the conflict is believed to have killed 14,000 people and displaced another 400,000 in Mogadishu alone. Many of the first to arrive in the United States as refugees were Darod, like Omar.

Somalis often gave nearly everything they had to rescue their families. Yaxia Osman, a former shopkeeper in Mogadishu whom I met in Mombasa in 2019, watched people being killed around him and then spent his entire savings, totaling roughly $30,000, renting trucks to get his extended family to the border. Most displaced Somalis, who were a great deal poorer than Osman, simply began walking to places the war hadn’t reached yet. Abdullahi Ali Aden, a refugee I met at the Dadaab complex of camps in the Kenyan desert in late 2019, hiked barefoot to the Somali-Kenyan frontier after the outbreak of war. His family of five slept by the roadside; they survived because they brought along their flock of 28 goats, nearly half of which they slaughtered during their weeks-long trek to relative safety.

Outside the house of President Ali Mahdi in Mogadishu, 1991ALEXANDER JOE/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

Outside the house of President Ali Mahdi in Mogadishu, 1991ALEXANDER JOE/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

The story of the conflict’s most famous refugee is also one of the war’s stranger escapes to safety. Omar’s family stayed in Mogadishu for months after Barre’s ouster. One night, per Omar’s memoir and various other accounts she’s given, attackers from an unspecified militia group tried to scale the gates and walls of the compound as the family gathered in their courtyard after dinner. As Omar recalls in her book, the family locked itself in the compound’s main building; the young Omar hid under a bed. A “volley of gunfire” clattered the front gate. An aunt and an older sister recognized two of the militants, who they had known since childhood, and boldly began negotiating for the family’s lives. The attackers withdrew when the two women effectively shamed them into leaving.

Omar’s father and grandfather put their escape plan into action early the next morning. Omar and a female relative traveled to the coastal city of Kismayo in the back of a truck and eventually got out of Somalia by air: “We were smuggled out of the country at great cost on a small plane used to bring in contraband shrimp,” she writes. “My aunt and I traveled in one aircraft, and my grandfather in another.” According to Omar’s memoir, her father did not come with her—she does not explain what route he took into Kenya.

The Mogadishu airport shuttered on December 31, 1990 as fighting intensified; chartering international flights in a Somalia rapidly descending into anarchy was practically unheard of. Yet by Omar’s recollections, her extended family of some 20 people successfully evacuated a country of militant checkpoints, firefights, and inter-clan violence by truck and by multiple aircraft. Such an escape required a combination of resources, luck, and advanced planning that almost no other escapees had. Barre himself arrived in Kenya later in 1991, by land.

The origin myth of the Minneapolis Somali American community involves a turkey factory three hours to the west, in a town called Marshall, Minnesota, which has a current population of 13,000. During the icy winter of 1992, a group of about 20 young men made their way to Marshall, where a Somali man worked as one of the factory’s shift supervisors. The newcomers barely spoke English, and had few marketable skills. They were living through a tragedy that was both alien and invisible to their new neighbors, almost all of whom were Christian and white, and had no first-hand experience of civil war.

The Somalis came to America as refugees from a conflict that had killed their friends and relatives, wiped out everything they had saved or built, and stranded family members in slums and refugee camps across East Africa and the Middle East. The men had mostly lived in San Diego upon arriving in America, and fanned out to seek work wherever they could find it. They slept in the bus station in Sioux Falls the night before the final leg of their trip to Marshall, a place where they were not made to feel especially welcome. No one would rent them housing—the workers lived in trailers that the factory’s owners provided. In the freezing pre-dawn hours they would queue at a payphone in the center of town to call relatives in Nairobi or Sanaa or London to learn who had and hadn’t made it out of Somalia. A police car would sometimes pull up, with the officer inquiring as to why these Black men were gathering at such an odd time of day, wrapped in blankets.

It was not until the infamous October 1993 Black Hawk Down incident, in which militants killed 19 American soldiers in Mogadishu’s Bakaara Market, that the people of Marshall understood that these mysterious new neighbors were survivors of a living hell, dispossessed by a war that had consumed everything of their previous lives. The townsfolk grew more willing to rent to the Somalis, who began to learn English and develop a better grasp of life in rural Minnesota. The Somalis found a lot to like about Marshall. There was an abundance of low-skill jobs, along with a Minnesotan ethos of steely reserve that tended toward leaving people alone regardless of how outside the mainstream they might appear. “In Somali culture there is a concept called sahan—scouting,” explained Yusuf. Somalis discovered they could live relatively comfortably in Minnesota and still have enough money left over to support their relatives overseas. “Once they found out that they were able to feed their families in Ethiopia or in Kenya or in Yemen, the word was out.”

Somali refugees who the U.S. government had resettled in the warmer and seemingly more hospitable climates of San Diego and northern Virginia gradually made their way to the frigid north of their new country, a place whose bleak climate, landlocked geography, gunmetal skies, and homogeneously white and Christian population amounted to nearly the polar opposite of the place they had fled.

From Marshall and other small towns, the Somalis began to look toward the state’s largest metropolis, an emerging city in need of taxi drivers, factory workers, and hotel staff. It helped that Minneapolis was an altogether calmer and safer place than other major American population centers.

Like any creation myth, the story of how Somalis got to Minneapolis is interesting for what it omits. A significant number of Somalis made it to Minnesota because of the U.S. State Department’s refugee resettlement program, which identified the chilly upper midwestern state, then roughly 97% white, as a place in need of fresh supplies of impoverished foreigners. More importantly, the United States cared about Somalis relative to other imperiled populations because of a perceived national interest in helping people who had suffered on America’s behalf. Barre’s regime had become a U.S. ally during the tail end of the Cold War, and in December of 1992, the United States sent 25,000 soldiers to Somalia to supplement a United Nations force in a last-ditch attempt to stabilize the country. American policy in Somalia had been a failure, but acceptance of Somali refugees, who would be on track to receive the globally coveted privilege of U.S. citizenship after just five years, was proof at the time that America would meet its moral obligations to its foreign partners, even when its bets went wrong.

By March of 1995, all foreign troops had withdrawn from Somalia, as the conflict deepened into a chronic social condition that endures to this day. The exodus of some 18,000 Somalis to the United States by the end of 1996, and nearly 110,000 by the end of the 2010s, included American security partners and senior Barre regime officials with blood on their hands, as well as average Somalis with family in the United States from before the outbreak of the war, along with others who got incredibly lucky.

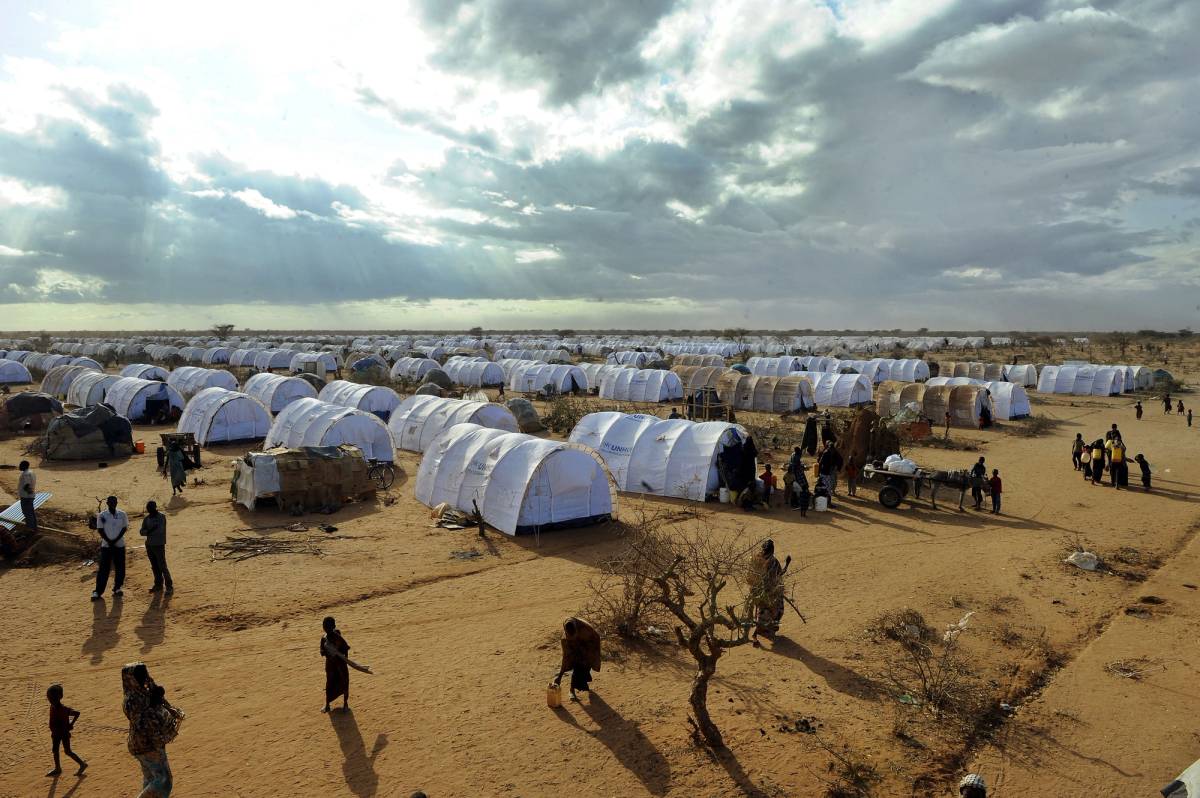

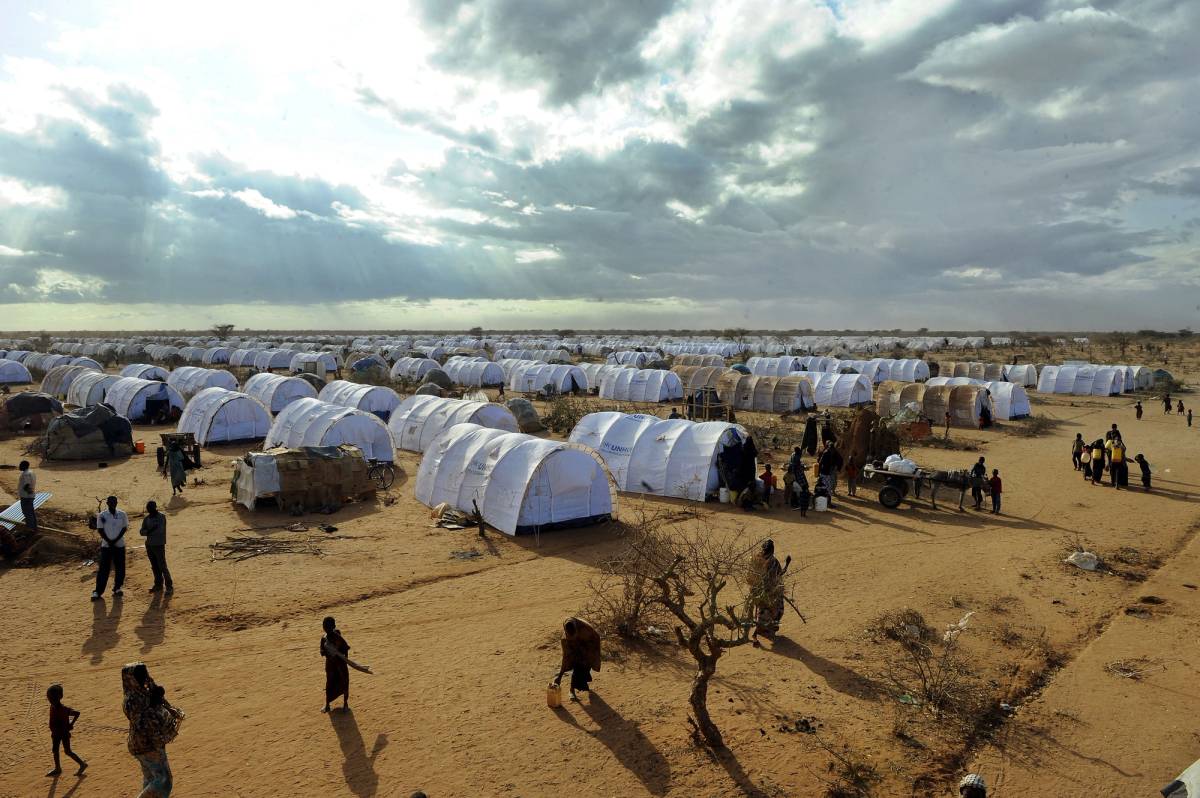

While the most fortunate minority of Somali refugees wound up in America, a far greater number became marooned in Dadaab, an hour’s flight from Nairobi in eastern Kenya. Despite its closeness to East Africa’s most important city, Dadaab is a desert twilight zone, almost impossible for a non-Kenyan to visit: In late 2019 a trip there required permits from the country’s Department of Refugee Affairs, followed by multiple layers of permission from various U.N. offices, followed by a brief police questioning when I finally arrived via a U.N. Humanitarian Air Services flight, followed by looks of astonishment from U.N. staff that I had even made it there at all. From the sprawling and blast wall-encased U.N. compound in the center of a nervous mud-shack town—al-Shabab, the brutal Somali al-Qaida affiliate, is alleged to operate nearby—it was a jolting 20-minute ride down a dust-clouded unpaved road before a visitor hit the first of the area’s three camps, which once formed the world’s largest refugee community and was then home to an estimated 200,000 people.

Few places on earth reveal the tenuousness of human existence quite like Dadaab, a manufactured catastrophe that also previews a maybe not-so-distant future in which most everywhere else on Earth is just as arid, featureless, and desperate. The land is dry and flat, more like sand than earth—after a brief rain, refugees began digging compacted dirt out of the roadways to use as building material. Inside the camps, mazes of winding footpaths are lined with makeshift thatched walls layered in discarded tins of cooking oil from the United States Agency for International Development, rows of metal American flags shimmering in the dull desert sunlight.

Modern-day Dadaab is the dark reverse image of the Somali American experience—it’s the fate from which Somali arrivals in the United States like Omar were saved. Many of the camps’ refugees have been stuck in the desert for decades because it is unsafe for them to return to Somalia, and because Kenya has placed punitively strict regulations on where Somali refugees can live and work. Most Dadaab residents are effectively banned from living outside the camps, which have no parks, no real libraries, few recreation centers, and few permanent buildings. Dadaab is not a war zone in the strictest sense. But it inflicts a cruel stasis: Few can leave, and life can’t progress for the residents until they leave.

Many of the refugees showed up at the Kenyan-Somali border sometime in the early ’90s only to spend the remainder of their lives waiting for the war to end, or for resettlement opportunities that never came. “We are in a caged place,” said Fardowso Abdullahi, who was born in the area’s Hagadera camp and whose parents had been livestock herders back in Somalia. “We cannot go anywhere.” When I traveled there in 2019, Western countries had only made 975 total annual resettlement slots available to Dadaab’s refugees. “It seems the world is tired of the Dadaab camps,” Abdullah Ali Aden, the elected chairman of Dushale camp told me. “A lot of people get a lot of knowledge here,” he added. “The knowledge you get is how to survive in a harsh life. It’s unbearable.”

‘Dadaab is not a war zone in the strictest sense. But it inflicts a cruel stasis: Few can leave, and life can’t progress for the residents until they leave.’ The Dadaab refugee camp in Kenya, the largest refugee camp in the world, 2011.TONY KARUMBA/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

‘Dadaab is not a war zone in the strictest sense. But it inflicts a cruel stasis: Few can leave, and life can’t progress for the residents until they leave.’ The Dadaab refugee camp in Kenya, the largest refugee camp in the world, 2011.TONY KARUMBA/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

Anab Gedi Mohammed, a child of poor shopkeepers from the Darod clan who had their home and business destroyed by militants from the rival Hawiya clan during the civil war, told me I was the fifth foreign journalist she had talked to in her life, including an Al Jazeera team, and that she’d had nearly identical conversations with all of us recalling her 27 years in Dadaab. “You do not know what it is like in the camp,” she said in English as I stood beside the door of her small compound, moments away from leaving. “Nothing will change.”

For a time, people briefly cared about Dadaab. On Aug. 11, 2018, Omar won the Democratic Party primary for Minnesota’s 5th Congressional District, putting her on track to be the first Somali American member of Congress and the first hijab-wearing congresswoman in American history. Reuters, The Guardian, and The Washington Post all reported that Omar and her family had lived in Dadaab for four years.

Memories of Ilhan Omar linger there. “There are people telling me that they were neighbors in 1994 … they could see she was a very intelligent woman,” reported Ali Aden, a refugee I met in Ifo, one of Dadaab’s three camps. My fixer, a journalist for one of the camp’s radio stations, said he was certain of the family’s former address: block A-7 of the dusty Ifo camp. “Ilhan was here,” said Shardid Abdikadir, a refugee and trader in Ifo’s sprawling marketplace. He recalled seeing Omar’s father there. “The way I remember, he was a very tall man. I haven’t met him, but we used to see each other.”

In fact, Omar never lived in any of Dadaab’s camps—she merely visited on a humanitarian mission in 2011—and any memories of her there are not based on real events. It is unclear how the notion that she spent time at Dadaab got started, or if Omar herself ever tried to correct this misperception, or even knew about it at all. Her family instead registered as refugees at Utange, outside of Mombasa, as she recounts in her memoir. In the early ’90s, any Kenyan refugee camp was a grim place, and Omar’s story shows how far determined people can go even when they’ve been deprived of seemingly every possible opportunity in life. As a result, Somalis look upon Omar as “an extended cousin who made it,” said Mohammed Ibrahim, a founder of the Anti-Tribalism Movement. “It says a lot about us. We’re very resilient people.”

Until the publication of her memoir Omar never talked publicly about her years at the Utange refugee camp in any real detail, which is perhaps one reason the impression grew that she had lived in Dadaab. Today, there is no outward sign that a refugee camp was ever in Utange, which looks like any of Mombasa’s many other palm-shaded outlying slums. It was Utange’s closeness to one of Kenya’s major commercial and population centers, which boasts a strip of fancy beach resorts and an old quarter thick with buildings left behind by British, Portuguese, and Arab conquerors, that made the camp’s 1997 closure inevitable. “There was always a language barrier—no one understood each other,” recalled Abdulla Ahmed, a peddler who lived next to the camp site before, during, and after the refugees were there. “It led to fights here—people’s homes were harmed on both sides. That’s why they decided the camp had to be liquidated.”

For civil servants and other former members of the Somali ruling class, it was common to register in Utange and live somewhere else. “Most of the people accommodated in Utange, they told me they lived in Mombasa. The elites that is—the poor people lived in the camps,” said Mohamed Ingiiris, a visiting professor at the African Leadership Center at King’s College in London who grew up in Somalia and lived there until 2002.

Willis Okech, a journalist with The Standard newspaper who covered the refugee influx into Mombasa in the 1990s, had a similar recollection. “Utange refugees were the poor ones. Most of them were transferred to Dadaab. The rich ones were never transferred. They could get a refugee ID that allowed them to stay anywhere they wanted.” Yaxia Osman, the former Mogadishu shopkeeper, recalls that “people lived on both sides—you lived in the camp, but you also lived in the city.”

Omar writes in her memoir that she was reunited with her father in Utange in 1992, after the flight that took her from coastal southern Somalia into Kenya. The camp was a place of extraordinary suffering: Omar watched helplessly as a beloved aunt died of malaria. Her father submitted his family to the U.N.’s refugee agency as resettlement candidates. After an interview with U.N. staff, Omar and her immediate family “earned one of those golden tickets to America,” she writes, with no further explanation given—she doesn’t say which family members secured the “golden ticket,” or what made her family an ideal resettlement case from the U.S. government’s perspective, or how long the process took between the initial application and the issuing of the family’s refugee visas.

Omar visited Dadaab on that relief mission in 2011, but she is a nonpresence in Utange. In late 2019, one of the only surviving structures from the area’s six years as a refugee camp was a peak-roofed, one-story building whose bottom half was still painted in U.N. powder blue. It was now an orphanage, where children played on a rusting swingset and a broken-down Volkswagen Beetle.

Francis Kinyua, the orphanage director, pulled up a plastic chair and offered to tell me “the history of this place” as we sweltered under the high, swaying palms. “Before the refugees, life was almost sleeping. There were only trees, no noise.” He breezily accused the refugees of smuggling weapons into the camp but also said he admired his former neighbors. “The world is becoming a global village and economy, and the Somalis knew that a long time ago when everybody else was not aware.” He claimed that refugees who had kept up their foreign business contacts would ship consumer electronics into Mombasa. “With the entry of Somalis, almost every household owned a TV or radio,” he claimed. The man had never heard of Ilhan Omar.

Modern-day Dadaab is the dark reverse image of the Somali American experience—it’s the fate from which Somali arrivals in America like Omar were saved.

Typically, the U.N. provides countries offering resettlement with the names of potential candidates, a laborious and bureaucratic process that can sometimes drag on for the better part of a decade. But in the mid-’90s, the United States often made slots available to accommodate former political or security partners or to reunite the families of people who had already made it stateside.

American acceptance of displaced Somalis wasn’t strictly a humanitarian enterprise. Superpowers operate at such a vast scale that their failures often contain the germ of some future opportunity. American policymakers realized that Somali refugees could be an exploitable channel of communication and patronage moving from west to east, with Somalis in the United States acting as a ready-made pathway into the anarchic vacuum that contained Africa’s longest coastline, near one of the world’s most important maritime chokepoints. A safe, prosperous, and pro-American Somali diaspora could become an asset for U.S. defense and intelligence planners, a means of pursuing American security interests in a stateless void where a half-dozen countries competed for influence. The highest ranks of the Somali government are now stacked with people who spent significant time in the United States, including Mohamed Abdullahi Farmaajo, the country’s president between early 2017 and this past May, and a longtime Buffalo-area resident who holds American citizenship.

Omar has been notably guarded in explaining the circumstances of her family’s arrival in the United States. In October of 2018, months after winning the Democratic congressional primary, she showed Minneapolis Star-Tribune reporter Stephen Montemayor “cellphone photos of documents from her family’s U.S. entry in 1995 after fleeing Somalia’s civil war,” listing her father and six other siblings as relatives. Montemayor wrote that these documents were “refugee resettlement approval forms and identification cards,” but also notes he was given no opportunity to authenticate them or to probe them in depth. In an email exchange with the Minneapolis lawyer and conservative writer Scott Johnson, Montemayor wrote that “Omar did not allow me to jot down names or provide a copy of the images.”

Omar writes in her memoir that she arrived in New York with her father, where she had a strongly negative first impression of the United States as grimy, graffiti-covered, and heartless. She recalls her disgust at length: “To be promised a utopia only to be brought to a city or town that might have a little less trash and crime and a few more buildings than where you came from is disorienting and disappointing.” In some ways America was even worse than where she’d come from: “When we lived in Somalia, in the big city, even next to the major outdoor market, I never saw a person who slept on the street while others just went about their day. That concept did not exist in my country’s communal society.”

In her memoir, Omar doesn’t consider the possibility that her failure to see or notice extreme poverty, which certainly existed in Mogadishu even before its descent into anarchy, was a function of her young age or her privileged, cloistered upbringing, rather than proof of the superior social solidarity, compared to the United States, of a Somalia on the brink of three decades of civil conflict. “In Kenya, we saw groups of young men hanging out on the street in dirty clothes,” she continues. “The adults talked about how they were on drugs, but they didn’t seem completely dejected like the old woman I saw lying across a New York City park bench with only her shopping cart as protection. The Kenyan street kids weren’t treated like objects to be walked around and ignored.” The favorable comparison of Kenya to the United States is especially attention-grabbing, given the East African nation’s long and arguably continuing history of official discrimination against both Somali refugees and native-born Somalis.

Northern Virginia, the first place Omar’s family settled, has had a small Somali community since the early 1980s. During Barre’s time, Somali elites who had a chance to get an education in the United States often chose to come to Washington, D.C., home to the country’s embassy. Several of Barre’s top henchmen ended up living in the greater D.C. area after the war, including Hussein Kulmia and Ali Samatar, two of Barre’s former vice presidents, the latter of whom was considered among the most brutal of the dictator’s deputies. Yusuf Ali Abi, an army colonel who participated in the destruction of Hargeisa, had quietly lived in the area for 17 years until he was sued over alleged past human rights abuses in 2019.

Most of the Somalis in the D.C. area weren’t quite so prominent. “In that time, 90% of them were cab drivers,” explained one member of the northern Virginia community whose father had been a senior Barre-era security official. “Ambassadors ended up here. But the who’s who went to Canada, Europe. Washington’s very tough, man. In Washington you have to work.” One benefit of America in the mid-’90s, though, was that a single refugee could sponsor the resettlement of numerous family members. Hundreds of people would arrive in town and then leave for Minneapolis within a few months. The source said that Omar had family in the D.C. area that included an older female relative who had worked for the Somali Central Bank under Barre; a Nairobi-based former senior politician in a post-civil war Somali government recalled meeting this Omar relative in northern Virginia in the 2000s. Although Nur Said found work in a local airport, the family’s stay in northern Virginia was relatively brief. Omar’s maternal grandfather had already settled in Minneapolis, according to her memoir, although his path from Kenya to the Midwestern city goes largely unexplained.

For Somali refugees on either coast, Minnesota was the real land of opportunity in the 1990s. Mohamed Amin Ahmed, founder of Average Mohamed, an anti-extremism nonprofit in the Twin Cities, also made the journey from Virginia to Minneapolis not long after reaching the United States. He said it was possible for a non-English speaker who had arrived in the Twin Cities in the morning to have a $16 per hour job as a foundry worker by nightfall. For Somalis, the draw went far beyond easy employment. As Ahmed put it: “When I came from Virginia and got off the plane a Somali guy helped carry my baggage. The cab driver was Somali. The hotel check-in desk clerk was Somali. The mosque was Somali. I went to a Somali restaurant. That’s how I knew it was home.”

Today, the Twin Cities are the largest star on the globe-spanning map of the Somali diaspora—more politically influential than London, richer than Toronto, arguably more important than even Nairobi, despite being a fraction of its size. In a world made small by cheap air travel, modern communications technology, and the often unforeseen complexities of American policy, an arcane social or political dispute in a distant country can create new and often vibrant subcultures in places that have little to no previous connection with those communities’ places of origin.

After the outbreak of the civil war, Somalis considered America a better destination than Europe; it was perceived as less racist and wasn’t seen as incentivizing idleness the way European societies were believed to. That perception endures among those who remember the early years of resettlement. “Over there they don’t call you immigrants, they call you foreigners,” said Hashi Shafi, a community activist in Minneapolis. “In the U.S., [refugees] only got eight months of welfare. That leads many Somalis to be hard workers.”

Somalis remained tightknit regardless of where they landed. “The social fabric is very strong,” said Ahmed Asmali, a businessman and community leader in Eastleigh, Nairobi’s rambunctious Somali downtown. “If someone sends $100 to the Twin Towers,” he said, naming a nearby apartment complex, “it gets divided to 100 people.”

Because of the particularity of Somali language and culture, the power of family and clan ties, and the still-reverberating shock of losing their homeland, the diasporic centers don’t feel quite as far apart as they are geographically. They don’t feel all that far from Somalia either, even when Mogadishu is half a planet away. Yussuf Hasan Abdi, the member of parliament for Eastleigh, said that Nairobi has its specific hangouts for Somali political factions, restaurants and hotel lobbies where backers of a given party or political figure gather. This was characteristic of other diasporic centers, including in the United States. “It’s everywhere—even in Minnesota and in London it’s exactly mapped out,” Abdi told me when I met him in Nairobi in 2019. “It’s a mirror of the problems of Somalia.”

read more..

Parada izraelskich żołnierzy/ fot. PINN HANS (GPO)

Parada izraelskich żołnierzy/ fot. PINN HANS (GPO) Droga bez powrotu [komentarz do parszy Be-szalach]

Droga bez powrotu [komentarz do parszy Be-szalach] Przed przekroczeniem Morza Czerwonego Izraelici byli przerażeni. Gdy jednak postawili pierwsze kroki, nie było już odwrotu[1]. Oczywiście później narzekali na brak wody i jedzenia, ale ich zdolność do walki i pokonanie Amalekitów pokazały, jak bardzo się zmienili. Przekroczyli Rubikon. Ich łodzie zostały spalone. Mogli patrzeć tylko przed siebie.

Przed przekroczeniem Morza Czerwonego Izraelici byli przerażeni. Gdy jednak postawili pierwsze kroki, nie było już odwrotu[1]. Oczywiście później narzekali na brak wody i jedzenia, ale ich zdolność do walki i pokonanie Amalekitów pokazały, jak bardzo się zmienili. Przekroczyli Rubikon. Ich łodzie zostały spalone. Mogli patrzeć tylko przed siebie.