Agata Dobosz

Łempicka dokładnie zacierała po sobie ślady. Ujawniała pojedyncze wątki swej biografii. Nie unikała przy tym koloryzowania i zasłaniania się… brakiem pamięci.

Do dziś dokładnie nie wiadomo, kiedy i gdzie urodziła się malarka. Najczęściej uznaje się, że przyszła na świat 16 maja 1898 roku w Warszawie, prawdopodobnie jednak jest to nieprawdziwa informacja, którą zmyśliła sama Tamara. Według niektórych biografów Łempicka urodziła się raczej w Moskwie i to dwa lata wcześniej – artystka lubiła też odejmować sobie lat.

Co ciekawe, młodsza siostra Tamary, Adrianna, nigdy nie ukrywała rosyjskiego pochodzenia rodziny. Łempicka z kolei wolała zatajać fakt, że jej matka Polka, pochodząca z bogatej rodziny Malwina Dekler, wyszła za mąż za rosyjskiego Żyda, zamożnego kupca Borysa Gurwika-Gorskiego. Tamara o wiele bardziej związana czuła się z Warszawą i polską rodziną ze strony matki. Deklerowie należeli do elity, w ich domu często bywali słynni pianiści – Ignacy Paderewski i Artur Rubinstein, a to bardzo imponowało Tamarze. W oficjalnych dokumentach wolała więc podawać fałszywe informacje o swoim pochodzeniu, podkreślając polskie korzenie i tym samym unikając wspominania o rosyjskim obywatelstwie.

„Potrafię zrobić to lepiej!”

Dzieciństwo Tamary było co najmniej luksusowe. Dzięki zamożnej rodzinie nie tylko mogła bywać na balach, recitalach i koncertach w letniej siedzibie Romanowów, lecz przede wszystkim miała szansę zdobyć dobre wykształcenie. Uczęszczała do elitarnych szkół. Uczyła się gry na pianinie i języków obcych. Już w wieku kilku lat zaczęła symulować problemy zdrowotne, aby wymuszać coroczne wakacje we Włoszech. Jeździła tam ze swoją babcią Klementyną Deklerową i podziwiała dzieła renesansowych artystów. Pierwsze spotkania ze sztuką zaczęły kształtować jej estetyczną wrażliwość.

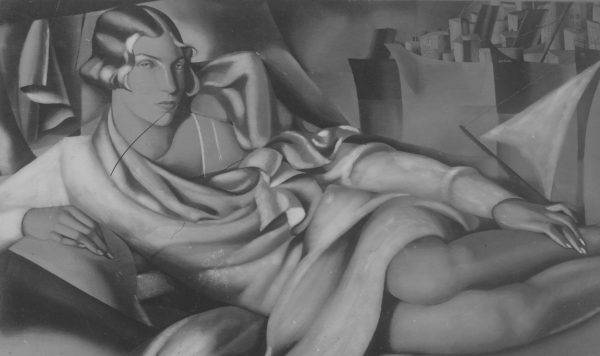

fot.Tamara Łempicka/Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe/domena publicznaTamara Łempicka, „Dwie siostrzyczki”

fot.Tamara Łempicka/Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe/domena publicznaTamara Łempicka, „Dwie siostrzyczki”

Cieniem na tej sielance położyło się nagłe zniknięcie jej ojca. Malarka w dorosłym życiu utrzymywała, że rodzice się rozwiedli. Bardziej prawdopodobne jednak jest to, że Borys Gurwik-Gorski popełnił samobójstwo. Jak stwierdziła Małgorzata Czyńska, autorka książki „Najpiękniejsze kobiety z obrazów. Prawdziwe historie”: Tamara wymyśliłaby wszystko, byle nie wspominać o samobójstwie ojca. Rodzinny dramat należał do jednej ze skrzętnie ukrywanych przez malarkę tajemnic.

Choć to Adrianna, młodsza siostra artystki, od najmłodszych lat zadziwiała talentem do rysunku, Tamara szybko udowodniła, że i jej nie brakuje malarskich zdolności. Gdy matka dziewczynek zamówiła u wybitnego lokalnego artysty pastelowy portret córek, Tamara – po obejrzeniu efektu – wprost wyraziła swoje niezadowolenie. Zmusiła Adriannę do pozowania i sama zabrała się do pracy. – Postanowiłam, że potrafię zrobić to lepiej. Nie znałam techniki malarskiej, nigdy wcześniej nie malowałam, ale to było nieważne – opowiadała po latach. Ta pewność siebie stała się fundamentem jej wyzwolonego wizerunku.

Z gęsiami na sznurku

W 1911 roku Tamara przeprowadziła się do Sankt Petersburga, aby zamieszkać u swojego wujostwa, Stefy i Maurycego Stiferów. Zaczęła uczęszczać na kurs rysunku w Akademii Sztuk Pięknych. Dzięki krewnym mogła brać udział w bogatym życiu towarzyskim i kulturalnym. Chodziła „na koncerty do Carskiego Sioła, na przedstawienia baletowe do Teatru Maryjskiego, na przyjęcia u księżnej Iriny Jusupowej, kuzynki cara Mikołaja, czy na ślizgawkę”.

Na jednym z balów maskowych wypatrzyła Tadeusza Łempickiego. Przystojny młody prawnik, otoczony wianuszkiem kobiet, zwrócił jej uwagę. Jak się okazało – z wzajemnością, gdyż Tamara tego wieczoru była przebrana za pasterkę i na sznurku prowadziła żywe gęsi. Trudno było jej nie zauważyć. Łempicki miał wybitne pochodzenie. Jego ojciec, Julian Łempicki, herbu Junosza, wywodził się ze szlachty i pełnił funkcję przedstawiciela Towarzystwa Kolei Warszawsko-Wiedeńskiej. Matka, Maria Norwid, była spokrewniona z poetą Cyprianem Kamilem Norwidem.

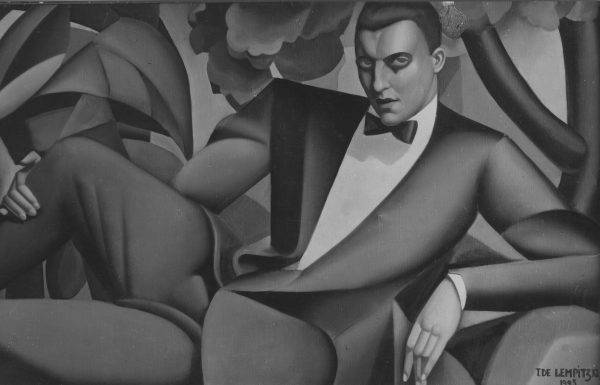

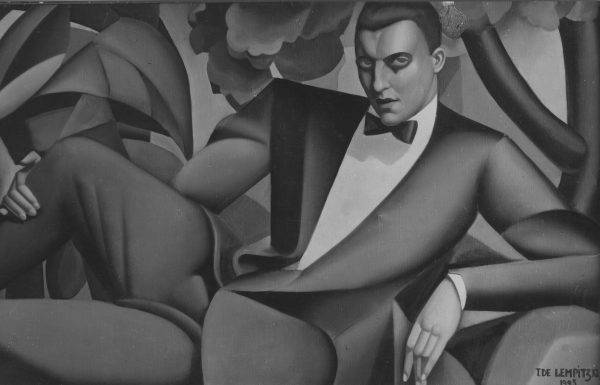

fot.Tamara Łempicka/Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe/domena publiczna Tamara Łempicka, „Portret markiza J. d’Afflito”

fot.Tamara Łempicka/Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe/domena publiczna Tamara Łempicka, „Portret markiza J. d’Afflito”

Ślub młodej pary odbył się około cztery lata później – w 1915 roku albo na początku 1916. Tamara mogła mieć wtedy osiemnaście lat. 16 września 1916 roku na świat przyszła ich jedyna córka – Maria Krystyna, którą rodzina pieszczotliwie nazywała Kizette. Beztroskie życie małżonków przerwał wybuch rewolucji październikowej w Rosji. Tadeusz został aresztowany przez bolszewików, a zrozpaczona Tamara próbowała go uwolnić. Była gotowa zrobić dosłownie wszystko. I zrobiła. Szwedzki konsul obiecał pomóc jej wydostać Tadeusza z więzienia i uciec z Rosji, ale postawił warunek – Tamara spędzi z nim noc. Artystka się zgodziła i niedługo potem spotkała się z mężem w Kopenhadze. Stamtąd ruszyli do Paryża, gdzie osiedli. Jakiś czas później dołączyły do nich matka i siostra Tamary.

Przemyślana kreacja

W Paryżu Tamara musiała wyprzedać swoją biżuterię, którą przemyciła z Rosji, aby opłacić małe mieszkanie. Pogrążony w depresji Tadeusz nie mógł, a może nie chciał znaleźć pracy. Między małżonkami coraz częściej dochodziło do awantur i przemocy fizycznej. To Adrianna namówiła Tamarę do dalszego studiowania malarstwa. Tamara uznała to za dobry pomysł, ale – jak zauważa Małgorzata Czyńska: nie zamierzała powielać schematu biednego artysty na zimnym poddaszu. Jeśli miała malować, to z sukcesem. Jasno określiła swój cel. Powtarzała, że za każde dwa sprzedane obrazy będzie kupować sobie bransoletkę, aż do dnia, gdy cała pokryje się diamentami od nadgarstków do ramion.

Łempicka najpierw chodziła na zajęcia do Académie Ranson, gdzie uczył ją przyjaciel Paula Gauguina – Maurice Denis. Następnie została studentką André Lhote’a, w którego twórczości nowatorski kubizm łączył się z tradycyjnym akademizmem. Mimo że Tamarze udało się zdobyć całkiem przyzwoite wykształcenie, w późniejszym czasie twierdziła, że zawsze była samoukiem…

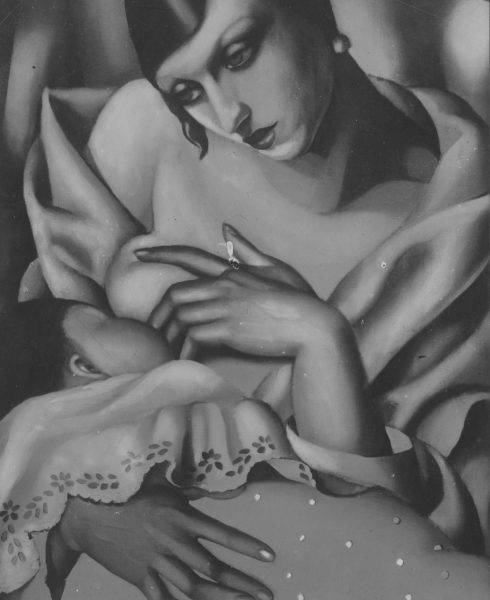

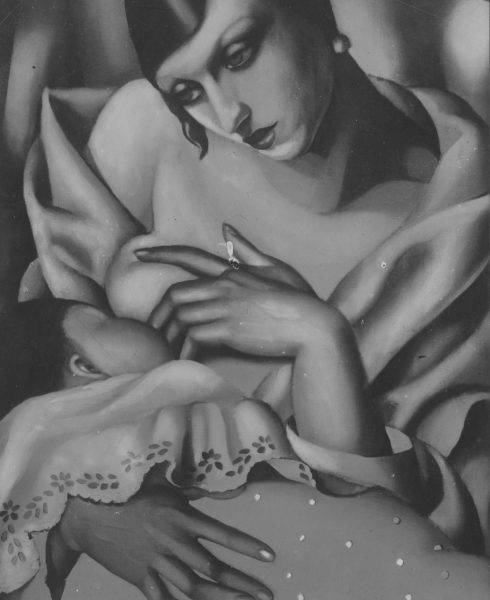

fot.Tamara Łempicka/Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe/domena publiczna Tamara Łempicka, „Kobieta karmiąca”

fot.Tamara Łempicka/Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe/domena publiczna Tamara Łempicka, „Kobieta karmiąca”

Pierwsze poważne próby malarskie Łempickiej szły w parze z przemyślanym budowaniem wizerunku. Przeniosła się do modnej dzielnicy Montparnasse, aby brylować w artystycznym towarzystwie. Regularnie bywała w kawiarniach. Malowała nawet kilkanaście godzin dziennie, ale nie przeszkadzało jej to w całonocnych wycieczkach po pubach. Nawiązywała kolejne romanse – i z mężczyznami, i z kobietami.

Każdą wolną chwilę spędzała w Luwrze, analizując słynne dzieła. Tradycyjna estetyka, którą tak chłonęła w muzealnych salach, przeniknęła do jej obrazów, ale w nowoczesnej, bardziej zgeometryzowanej formie. Charakterystyczne dla jej prac były także żywe, rozświetlone barwy, przez które namalowane obiekty wydają się bardziej trójwymiarowe. Tamara szczególnie dobrze odnalazła się w nurcie art déco, który rozwinął się w latach 20. To wtedy namalowała swoje najsłynniejsze dzieła: „Piękną Rafaelę” czy „Autoportret w zielonym bugatti”, a jej kariera nabrała rozpędu.

Propagatorka perwersyjnego malarstwa

Rozwój kariery wiązał się z coraz większą rozpoznawalnością Łempickiej. To z kolei przekładało się na sukces finansowy. Malarka wystawiała swoje prace nie tylko w Paryżu, lecz także za granicą, w tym w Polsce. Szczególnie popularna stała się wśród zamożnych arystokratów, którzy zamawiali u niej portrety, zazwyczaj naturalnej wielkości. To właśnie z portretów i odważnych aktów, takich jak „Andromeda”, „Adam i Ewa”, „Dwie przyjaciółki” czy „Akt siedzący”, Łempicka jest najbardziej znana. Rzadziej malowała martwe natury i pejzaże.

Krytycy różnie odnosili się do jej prac. Z jednej strony chwalili dbałość o szczegóły i staranne wykończenie obrazów, z drugiej potępiali artystkę za „cielesność graniczącą z kiczem lub przynajmniej grzechem” i nazywali ją „propagatorką perwersyjnego malarstwa”. Nie da się ukryć, że kobiece akty stworzone przez Łempicką wyraźnie emanują erotyzmem. W jej twórczości nie brakuje jednak sensualności i czujnego obserwowania portretowanych osób.

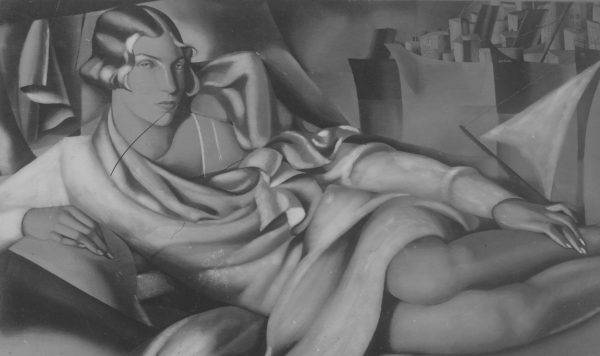

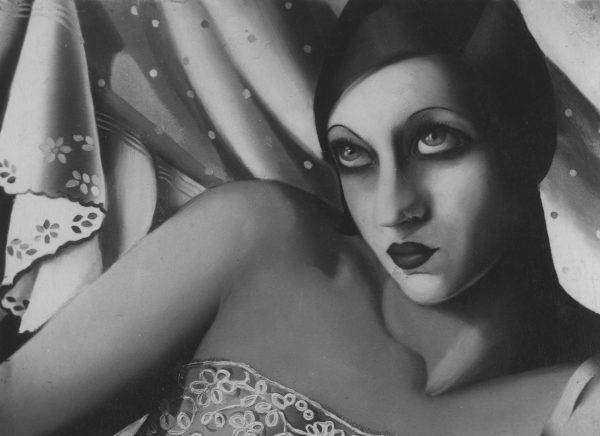

fot.Tamara Łempicka/Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe/domena publiczna Tamara Łempicka „Portret młodej kobiety”

fot.Tamara Łempicka/Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe/domena publiczna Tamara Łempicka „Portret młodej kobiety”

Potrafiła wypracować język malarski, którym oddawała symboliczne wizerunki. Za taki można właśnie uznać „Autoportret w zielonym bugatti”, o którym pisano, że przedstawia kobietę wyemancypowaną i wolną, kobietę-ikonę szalonego dwudziestolecia międzywojennego. Sama Łempicka starała się tworzyć i podtrzymywać wizerunek kobiety ambitnej, która posiada wszelkie niezbędne cechy, aby stać się symbolem swoich czasów. Gdy w 1932 roku udzieliła wywiadu warszawskiemu tygodnikowi „Świat”, reporter opisał ją w następujący sposób:

Sylweta zupełnie paryska. Duże, jasne, wnikliwe oczy, włosy blond i nos grecki, lekko zgarbiony. Usta ukarminowane i paznokietki wymanikiurowane ochrą. Wzrost, jak na kobietę, pokaźny. Stroje wymarzone, futra najdroższe! Budzi zaciekawienie już swoją prezencją.

Schyłek

Nawet jeśli w dwudziestoleciu międzywojennym nastąpiło pewne rozluźnienie norm obyczajowych, to styl życia Łempickiej wciąż budził kontrowersje. Malarka zdawała się nic z tego nie robić. Wręcz przeciwnie. Można odnieść wrażenie, że nader bogate życie towarzyskie, prowadzone zwłaszcza w nocnych porach, jak i liczne romanse, których nie ukrywała, stanowiły istotny element jej przemyślanego wizerunku kobiety niezależnej. Niemniej jednak nawyki malarki doprowadziły do kryzysu w jej małżeństwie, które ostatecznie zakończyło się rozwodem w 1927 roku.

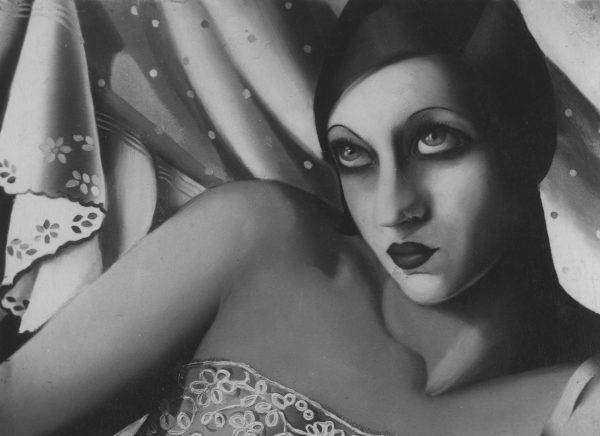

fot.Tamara Łempicka/Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe/domena publiczna Tamara Łempicka „Młoda dziewczyna”

fot.Tamara Łempicka/Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe/domena publiczna Tamara Łempicka „Młoda dziewczyna”

Siedem lat później Łempicka wyszła za mąż drugi raz, za barona Raoula Kuffnera, który był właścicielem największego majątku ziemskiego w Austro-Węgrach. Ze względu na żydowskie pochodzenie Kuffnera para zdecydowała się na wyjazd do Stanów Zjednoczonych. W Europie narastała fala faszyzmu.

W latach czterdziestych Tamara należała do ulubionych portrecistek gwiazd Hollywood. Wciąż prowadziła bujne życie towarzyskie, jednak jej gwiazda powoli gasła. Gdy w sztuce zaczęły dominować abstrakcyjne nurty, malarka próbowała zmienić styl. Eksperymentowała, tworząc surrealistyczne pejzaże i ekspresyjne abstrakcje. W 1978 roku „New York Times” nadal nazywał ją boginią ery automobilu o stalowych oczach. Mimo to artystka w końcu porzuciła malarstwo i po śmierci Kuffnera przeniosła się do Meksyku. Zmarła tam w 1980 roku. Zgodnie z ostatnią wolą Łempickiej jej prochy rozrzucono nad wulkanem Popocatépetl.

Bibliografia

-

- Claridge L., Tamara Łempicka: między art déco a dekadencją, Poznań 2009.

- Czyńska M., Najpiękniejsze kobiety z obrazów. Prawdziwe historie, Kraków 2014.

- Kozina I., Art déco, Warszawa 2013.

- Néret G., Tamara de Lempicka, Kolonia 2001.

- Potocka M., De Lempicka M., Tamara Łempicka, Olszanica 2020.

Jewish Employee Resigns From Now-Shuttered Kanye West School

Jewish Employee Resigns From Now-Shuttered Kanye West School Rapper Kanye West holds his first rally in support of his presidential bid in North Charleston, South Carolina, U.S. July 19, 2020. REUTERS/Randall Hill/File Photo

Rapper Kanye West holds his first rally in support of his presidential bid in North Charleston, South Carolina, U.S. July 19, 2020. REUTERS/Randall Hill/File Photo