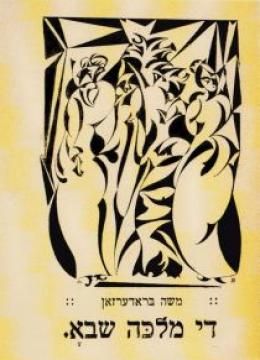

Mojżesz Broderson, okładka własnego poematu dramatycznego “Di malke Szwo (Królowa Saby)”, Farlag “Jung Jidysz”, Łódź 1921, ze zbiorów Biblioteki Narodowej w Warszawie

Mojżesz Broderson, okładka własnego poematu dramatycznego “Di malke Szwo (Królowa Saby)”, Farlag “Jung Jidysz”, Łódź 1921, ze zbiorów Biblioteki Narodowej w Warszawie

Jung Jidysz

Jung Jidysz

Magdalena Wróblewska

Jung Jidysz to grupa artystyczna działająca w Łodzi w latach 1919-1921, zrzeszająca twórców pochodzenia żydowskiego.

Do grona założycieli należeli: Jankiel Adler, Mojżesz Broderson, Marek Szwarc, Wincenty Brauner. Z grupą związanych było wiele postaci środowiska artystycznego – największą rolę odegrali: Henryk Barciński, Henryk Berlewi, Ida Brauner, Samuel Cygler, Zofia Gutentag, Icchak Kacenelson, Henoch Kohn, Pola Lindenfeld, Dina Matus, Mojżesz Neuman, Natan Szpigel i Władysław Wajntraub.

Jung Jidysz była jedną z kilku grup działających w okresie międzywojennym, związanych z nurtem ekspresjonizmu. Około 1917 roku w różnych miejscach w Polsce ujawniał się on w sztuce powstających ugrupowań artystycznych: Ekspresjonistów Polskich (później Formistów) w Krakowie czy Buntu i kręgu pisma “Zdrój” w Poznaniu. W Łodzi pod nazwą Jung Jidysz działała nie tylko grupa, ale od 1919 roku ukazywało się pismo pod redakcją Mojżesza Brodersona, w którym publikowane były manifesty tego środowiska.

Ekspresjonizm rozumiany był wówczas przez twórców niezwykle szeroko, jako ogół nowych zjawisk i dążeń w sztuce. Jankiel Adler utożsamiał go wręcz ze sztuką dwudziestego wieku. W różnych środowiskach dominowały odmienne poetyki, i tak na przykład Formiści łączyli ekspresję formy z kubistyczną syntezą, a czasem także futurystyczną dynamiką. Inny nurt wyznaczało środowisko poznańskich artystów inspirujących się, podobnie jak twórcy kręgu Jung Jidysz, tym co działo się w galeriach Berlina. Oprócz recepcji niemieckiego ekspresjonizmu, dla artystów łódzkich niezwykle istotna okazała się sztuka Marca Chagalla, co ujawniło się zwłaszcza w twórczości Adlera.

Historia tego środowiska jest dopiero rekonstruowana, do niedawna Łódź kojarzona była głównie z ugrupowaniami konstruktywistów. Odkrywaniu grupy Jung Jidysz na pewno nie sprzyjał fakt, że większość tekstów teoretycznych i programowych napisana została w języku jidysz, a specyfika twórczości w dużej mierze opierała się na jej wielokulturowym charakterze.

Artyści z Jung Jidysz działali na styku różnych kultur i religii, wykraczając daleko poza tradycję żydowską, odwołując się niejednokrotnie do chrześcijaństwa i symboliki różnych kręgów kulturowych. Środowisko łódzkie miało w tym czasie wielonarodowy charakter, stanowili je zarówno Żydzi z Rosji i Rosjanie, Niemcy i Polacy. Stąd w sztuce tego miejsca obecne były kwestie tożsamości narodowej, a także religii (obok katolicyzmu w Łodzi silny był protestantyzm, działali ortodoksyjni Żydzi i reformatorzy). Poszukiwano raczej płaszczyzny wspólnoty i porozumienia, dominowała postawa akceptacji dla odrębności społeczności stanowiących wspólnotę tego na wskroś nowoczesnego miasta.

Istotną inspirację dla twórców Jung Jidysz stanowiło właśnie miejsce, w którym działali. Dynamiczne miasto w okresie przyspieszenia gospodarczego, ciągłych zmian na tle ekonomicznym i społecznym było tematem i punktem odniesienia dla działań artystów. Z miastem i jego ikonosferą wiąże się też istotny w twórczości żydowskich malarzy pierwiastek prymitywu, tutaj utożsamianego z folklorem miejskim, estetyką szyldów i wystaw sklepowych, ale także aurą biednych, robotniczych dzielnic dynamicznie rozwijającego się ośrodka przemysłowego.

Choć pojęcie awangardy łódzkiej utożsamia się automatycznie z działalnością Władysława Strzemińskiego i Katarzyny Kobro, to jednak sztuka nowoczesna wcześniej znalazła swe miejsce w tym mieście. Wincenty Brauner (Icchak Brojner), malarz i grafik wykształcony w Berlinie, wielbiciel sztuki van Gogha (w hołdzie dla którego przyjął imię), założył przy ulicy Piotrkowskiej Salon Sztuki. Prezentował z nim prace własne oraz zaprzyjaźnionych artystów. Tam odbyła się w 1915 roku pierwsza wystawa indywidualna Marka Szwarca (Schwarza), malarza, rzeźbiarza i grafika tworzącego w Paryżu, zaznajomionego ze sztuką Marca Chagalla. Inną postacią z tego kręgu był Henryk Barciński (Henoch Barczyński), malarz i grafik, który zdobywał wykształcenie w pracowni Glickensteina w Warszawie. Do grona tego dołączył po proklamacji niepodległości Polski w 1918 roku malarz i grafik Jankiel Adler, przebywający wcześniej w Berlinie, blisko środowiska galerii “Der Sturm”. Prace wymienionych artystów stanowiły trzon dwóch ważnych ekspozycji, jakie miały miejsce w Łodzi wiosną i zimą 1918 roku, zorganizowanych przez Stowarzyszenie Artystów i Zwolenników Sztuk Pięknych.

Na początku 1918 roku padł pomysł zawiązania ugrupowania artystycznego pod nazwą Jung Jidysz. Wówczas do grona wymienionych artystów dołączył przybyły z Moskwy Mojżesz Broderson (Broderzon), który stał się przywódcą ideowym i najważniejszym teoretykiem grupy. Był nie tylko grafikiem, ale przede wszystkim poetą i dramaturgiem. Zadebiutował tomem “Czarne świecidełka” w języku jidysz. Obok Braunera, Schwarca, Barcińskiego i Adlera, do grupy dołączyły artystki: Dina Matus, Ida Brauner (siostra Wincentego), Pola Lindenfeld, Zofia Gutenberg, a także poeci: Icchak Kacenelson, Jecheskiel Mojżesz Neuman (Najman). Pierwszy człon nazwy grupy nawiązywał do silnych na początku ubiegłego stulecia tendencji do odnowienia sztuki i środków jej wyrazu. Drugie słowo wskazywało na charakter tożsamości członków grupy. Jidysz jest syntezą wielu języków i dialektów, sposobem komunikacji wypracowanym w Europie Wschodniej przez ludność pochodzenia żydowskiego w małym stopniu zaznajomioną z hebrajskim. Przez inteligencję jidysz uznawany był za język klas niższych. Twórcy zrzeszeni w Jung Jidysz używali go programowo, bo właśnie do tych grup społecznych kierowali swoje przesłanie.

Tę programową tożsamość oddawały hasła publikowane na łamach ich pisma: “Za sztukę! Za młody, piękny język żydowski!”. Wybierając jidysz artyści podkreślali specyfikę sztuki żydowskiej i jej odrębność, a zarazem jej eklektyzm i wielość odniesień kulturowych. Swój artystyczny przekaz formułowali na łamach “Jung Jidysz” nie tylko w słowie, ale także w obrazach, zamieszczanych licznie ilustracjach, co doskonale widać w redagowanym przez Brodersona pierwszym numerze pisma, który ukazał się z okazji święta Purim 14 marca 1919 roku. Zawierał on, podobnie jak kolejny, wydany z okazji święta Pesach 15 kwietnia, manifest autorstwa Brodersona, stawiający obok postulatów artystycznych hasła dotyczące moralnej i religijnej odnowy. W ostatnim numerze, z przełomu listopada i grudnia 1919 roku, ukazał się artykuł Adlera o Chagallu oraz przedrukowany został manifest Kurta Heynickiego “Dusza sztuki“. W publikowanych tekstach pojawiały się także często hasła o potrzebie zerwania z przeszłością, charakterystyczne dla wszelkich awangard międzywojnia.

Malarze Jung Jidysz brali aktywny udział w życiu artystycznym innych miast, wystawiali swe prace między innymi w Warszawie i Białymstoku, utrzymywali też stały kontakt z poznańskim Buntem. W 1921 roku wraz z Henrykiem Berlewim utworzyli “Salon futurystów, kubistów i prymitywistów”. Adler wystawił na nim dziewiętnaście prac – scen miejskich i przedstawień inspirowanych ikonografią Nowego Testamentu, tematyka biblijna obecna była również w większości spośród wystawionych dwudziestu pięciu obrazów Braunera. Część prac z tej wystawy została potem przeniesiona do Warszawy, na ekspozycję zorganizowaną w gmachu Gminy Żydowskiej przy ulicy Grzybowskiej.

W 1921 roku działalność grupy wygasła. Artyści nawiązali liczne kontakty zagraniczne w związku z wystawą prac Jankiela Adlera w Nowym Jorku, a także pobytem tego artysty w Düsseldorfie, gdzie zaprzyjaźnił się z członkami grupy Das Junge Rheinland. Zaowocowało to udziałem niektórych artystów Jung Jidysz i Buntu w 1. Międzynarodowej Wystawie Nowej Sztuki w Domu Handlowym Tietza w Düsseldorfie wiosną 1922 roku. Przy tej okazji zorganizowany został kongres założycielski Unii Artystów Postępowych, głoszących potrzebę wymiany i współpracy międzynarodowej artystów. Niedługo później Jankiel Adler uczestniczył w Wielkiej Berlińskiej Wystawie Sztuki zorganizowanej przez November-Gruppe.

W 1922 roku niektórzy artyści kręgu Jung Jidysz swą działalność zaczęli coraz silniej wiązać z teatrem. Broderson założył słynny teatr marionetek “Koźlątko” (“Chat Gadje”), w którym spełniał rolę autora tekstów, animatora i lektora. Niezwykłe, ekspresjonistyczne lalki przygotował dla niego Brauner, zaś muzykę do przedstawień komponował związany z Jung Jidysz Henryk (Henoch) Kochn. Zarazem artyści indywidualnie i grupowo kontynuowali działalność wystawienniczą. W 1923 roku odbył się między innymi indywidualny pokaz prac Szwarca w Polskim Klubie Artystycznym w Warszawie oraz retrospektywna wystawa prac Braunera w sali witrażowej Casina w Łodzi. W tym samym roku w Łodzi zaprezentowano Międzynarodową Wystawę Młodej Sztuki, zorganizowaną przez Unię Postępowych Artystów, podczas której udało się skonfrontować sztukę niemieckich artystów, między innymi z Der Blaue Reiter oraz Die Brücke, z dokonaniami polskiej awangardy.

Literatura:

- Jerzy Malinowski, “Malarstwo i rzeźba Żydów Polskich w XIX i XX wieku”, Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, Warszawa 2000;

- Przemysław Trzeciak, “Wokół ‘Jung Jidysz'”, “Midrasz”, nr 7-8/2001;

- Marek Bartelik, “Modele wolności: artyści łódzcy grupy Jung Jidysz 1919-1921”, “Midrasz”, nr 5/2006.

Zawartość publikowanych artykułów i materiałów nie reprezentuje poglądów ani opinii Reunion’68,

ani też webmastera Blogu Reunion’68, chyba ze jest to wyraźnie zaznaczone.

Twoje uwagi, linki, własne artykuły lub wiadomości prześlij na adres:

webmaster@reunion68.com