‘March 1968’ is a Polish movie. It’s also my story.

‘March 1968’ is a Polish movie. It’s also my story.

Tom Sawicki

When it became impossible to keep living there, my family left. The one parting gift from Poland was making us give up our citizenship

.

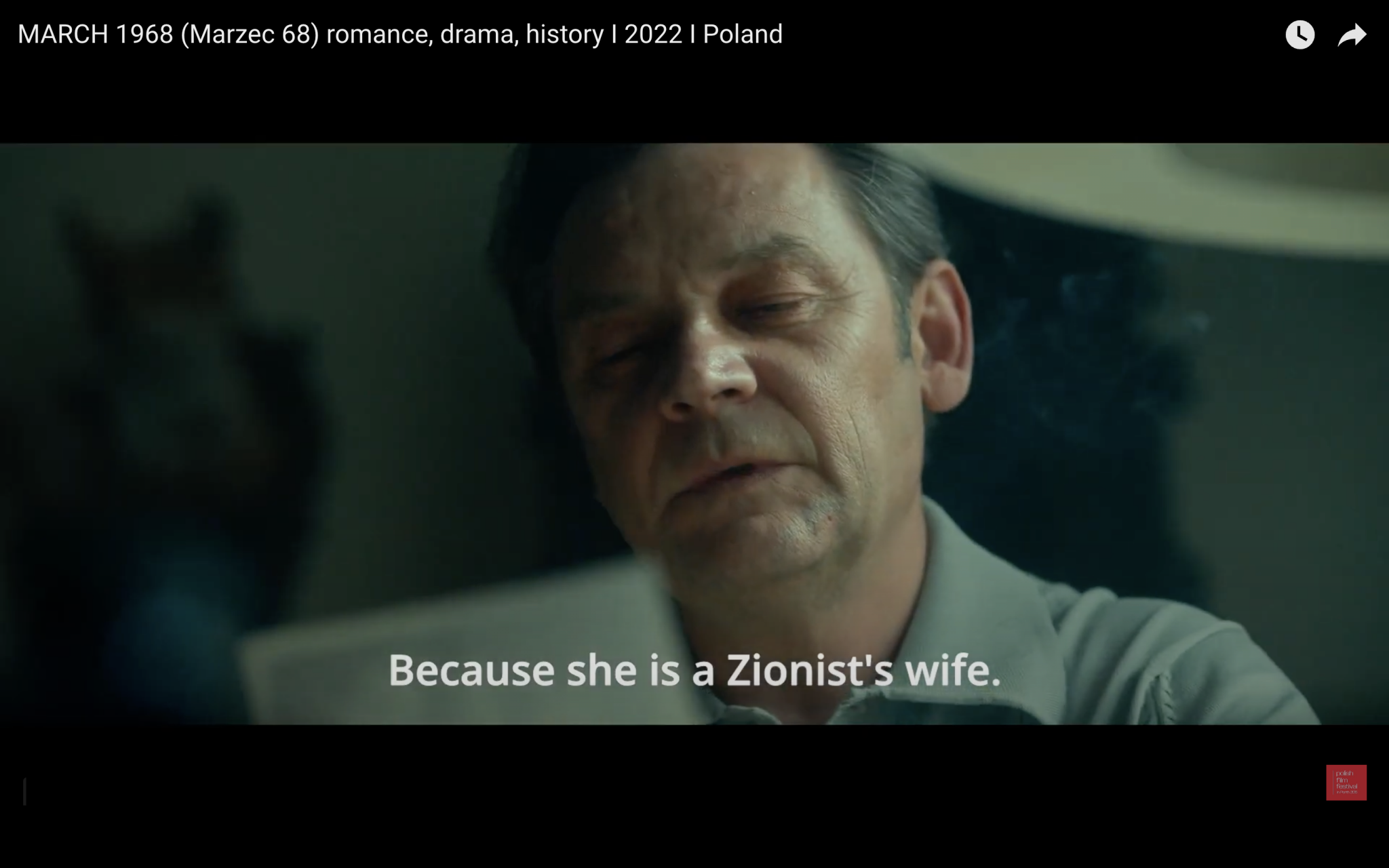

It sometimes takes a movie to tell the real story. No matter how many times I may have told my family’s stories to my wife and sons and many friends, I never felt that words alone presented the real picture. It is now a new Polish movie, “March ’68,” that accurately reflects one of the most important periods in the life of my family. Against the backdrop of newfound love between two young people, the movie presents the account of the events that led to the expulsion from Poland, where I was born and grew up, of some 13,000 Jews, including my family, practically the last remnants of the community that numbered 3.3 million before the Holocaust, and in many cases ethnic Poles married to Jews, for their alleged “Zionist” activities. The movie was shown this Hanukkah during the annual Jewish Film Festival at the Jerusalem Cinematheque.

I was only 16 in March 1968, and not directly involved, but the events shown in the movie were all around me. “March ’68” (“Marzec ’68,” in Polish) in Poland refers to major anti-government protests by students, academics, artists, and many others, in Warsaw and other cities between March 8-23, 1968. These were triggered first by Poland’s and the Soviet bloc’s reaction to the June 1967 Israeli victory in the Six-Day War, then by the censorship of a play written in the first half of the 19th century by the great Polish poet and dramatist Adam Mickiewicz (1795 – 1855) that spoke of the Czarist Russian oppression, and finally by an internal struggle between two different factions within the country’s ruling Polish United Workers’ Party (known as PZPR for its Polish initials) – the de-facto Communist Party. All this is succinctly and very clearly shown in the movie.

The June 1967 Israeli victory created an excuse for an antisemitic, or rather mainly “anti-Zionist” campaign in Poland which, following Moscow’s example, broke off diplomatic and all other relations with Israel. Subsequently, over the next few months, most Poles of “Jewish descent” who occupied senior and even mid-level positions in academia, medicine, the country’s economic and intellectual life, and other fields, were dismissed from work. The pretext was their “Zionist activities” coupled with “imperialist tendencies.” In the movie you witness what happens to a family that is left without a source of income and what choices remained for them. You also see that many Poles were more than happy to take part in the antisemitic campaign.

November 1967 was the 50th anniversary of the Soviet October Revolution. The Soviet-bloc countries were expected to mark the occasion with special celebrations. Warsaw’s National Theater chose to stage a modernist interpretation of Mickiewicz’s play “Forefathers,” with Gustaw Holoubek (think Poland’s Lawrence Olivier, for comparison) in the title role. Suffice it to say that according to Poland’s ruling party, the play whose negative reviews appeared in all the official major newspapers, “plunged a knife in the back of the Polish–Soviet friendship.” The play was ordered closed down after four performances. In the movie, it is not hard to understand the meaning of an early 19th-century play in its modern interpretation hinting at Soviet oppression.

Closing down the play did not sit well with many of Poland’s intellectuals, writers, and especially university students – Poland’s new generation was tired of the government’s dictates. Graffiti calling on the government to allow the play to continue appeared all over Warsaw. Students at many universities throughout the country distributed petitions and leaflets calling for an end to censorship. Finally, on March 8, a mass and distinctly peaceful rally took place in Warsaw, with speakers calling for civil liberties, including freedom of expression. However, once the rally ended and people began to disperse, they were brutally attacked by many hundreds of club-wielding police officers and the vodka-encouraged (yes!) so-called “volunteers” (think Iran’s Basij).

All this is shown in the movie with staged scenes and original footage from that day. The official media blamed “primarily those of Jewish descent” for the violence. In the movie, one also hears original reports from Radio Free Europe, which was the main source of information about the events at the time. (Polish Radio reported only on how much steel was produced in Poland that month.)

Last but not least was the internal struggle for the control of the United Workers’ Party, with a faction led by the Minister of the Interior, who had absolute control of the police and the “volunteers.” (I deliberately avoid naming them hoping their names will be erased from memory but if interested it is easy to Google them.) In the movie, it is made clear that the violence could have been prevented had the party head chosen to challenge the minister.

Following the March 8 events, the party head called for a general congress of the United Workers’ Party, which gathered in Warsaw on March 19. He delivered a two-hour speech in which he discussed the recent events, again blaming the violence “instigated especially by those of Jewish descent.” In one sentence in the speech, whose original brief black and white clip is shown, he also refers to “those of Jewish descent who do not wish to remain in Poland.” This was a signal to my family, and to many thousands of others, that Polish borders would be open to those who wish to get out. (The movie painfully shows what happens to the family of one of the main characters confronted with the choice of leaving Poland or having their daughter face the firing squad as a spy.) The party head also threatened to impose martial law should demonstrations continue and by March 23 Warsaw became quiet.

Different scenes in the movie reminded me of the time my mother, a seasoned pediatrician who was director of the neo-natal department at Warsaw’s Children’s Hospital, was fired. (My father’s boss at Warsaw University refused to fire him but he knew that my family would leave Poland soon). Different scenes reminded me of the time when the principal of my high school, Director Redlich (who was of Jewish descent), was replaced by a party apparatchik, and of the time when my chemistry teacher said that “now the Jews will not rule over us.” And I, knowing that my family will soon leave Poland, bravely called her in front of the entire class a “filthy antisemite” and for this, she gave me two F’s (which would have prevented my graduating had we remained in Poland).