La Revue Blanche

La Revue Blanche

MITCHELL ABIDOR

Tablet’s French literary ancestor was founded by three Warsaw-born brothers who were high school friends and classmates of Marcel Proust, and who published everyone from André Gide to Paul Claudel. Then came the Dreyfus affair.

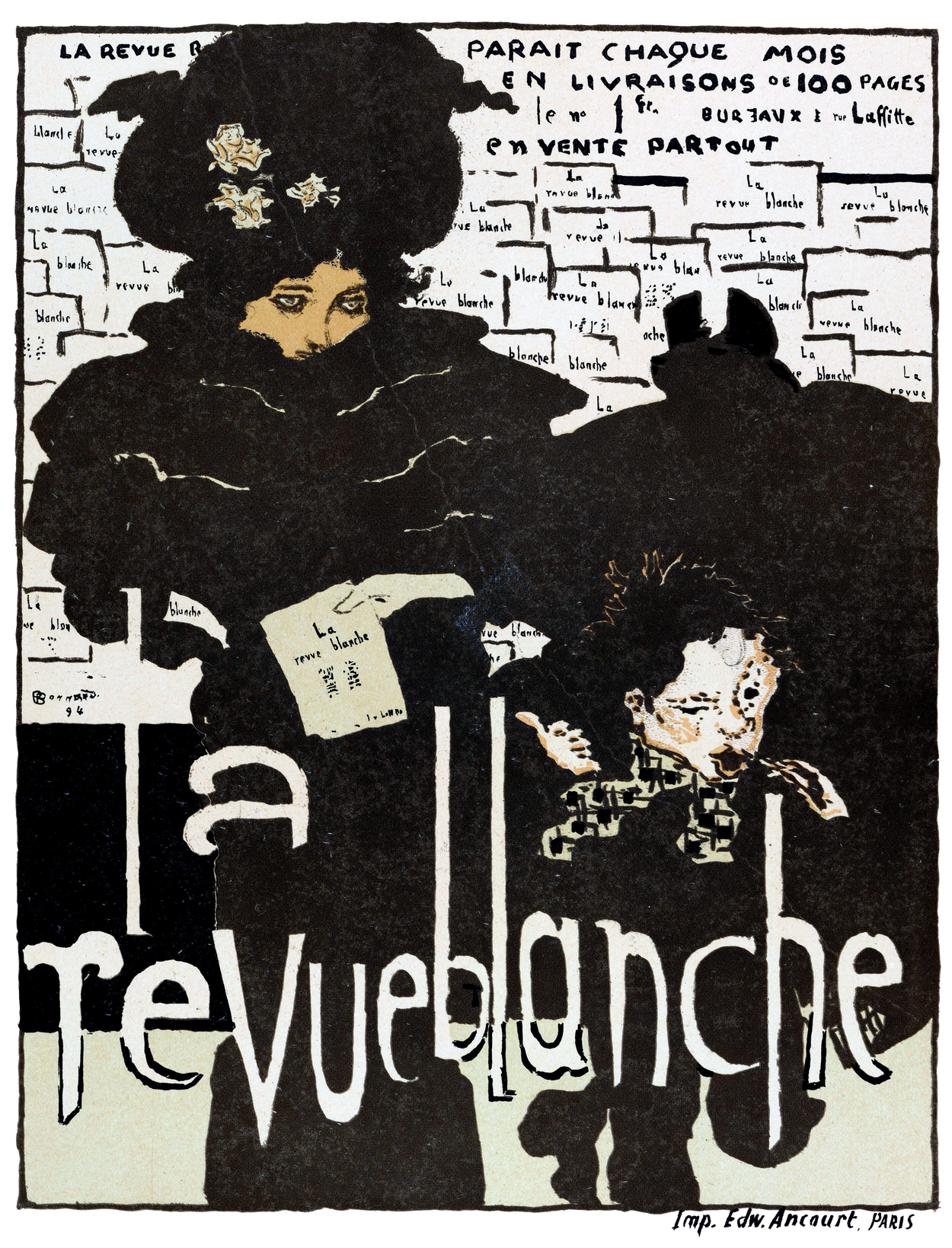

Revue blanche magazine poster, 1890sCALIMAX/ALAMY

Revue blanche magazine poster, 1890sCALIMAX/ALAMY

To burrow through the issues of La Revue blanche, the French political and cultural journal that was published from 1891 to 1903, is to experience awe at the breadth, reach, and openness of an important section of the French intellectual world of the time. In many ways, La Revue blanche can be said to define that world. Any random volume of the review can represent its entire run, demonstrating its impressive variety and cosmopolitanism. Volume 9, from 1895, includes an excerpt from André Gide’s early novel Paludes, translations from Edgar Allan Poe, August Strandberg, Alexander Herzen, and Knut Hamsun, along with essays by the great novelist and diarist Jules Renard. Among the poets we find Paul Claudel, Stéphane Mallarmé, Paul Verlaine, and Francis Jammes. Art was a strong point of La Revue blanche, and the three issues of this volume were illustrated by Toulouse-Lautrec and Félix Valloton.

The magazine was owned and edited by the Warsaw-born Natanson brothers, Alexandre, Thadée, and Alfred. The sons of a banker father who settled in France when the brothers were young, they attended one of France’s most prestigious high schools, the Lycée Condorcet, where Marcel Proust was among their friends. Their university studies destined them for lives among the solid bourgeoise, but it was the arts that drew them.

La Revue blanche, founded in Liège in 1889 but transferred to Paris in 1891, was in a sense a tribute to the success of Jewish emancipation, which had occurred a century earlier, thanks to the French Revolution. The Jewish presence in the pages and leadership of the review is unmistakable, cutting across political ideologies.

Sitting alongside the Natanson brothers at the head of the review was Lucien Muhlfeld, secretary of the editorial committee and former librarian at the Université de Paris. For 10 years, the future Jewish socialist prime minister of France Léon Blum wrote articles and theater and book reviews, both under his own name and pseudonymously. Among the magazine’s other Jewish contributors were the novelist Tristan Bernard, the first Dreyfusard; the anarchist Bernard Lazare; and the pacifist and Esperantist Gaston Moch.

This Jewish role did not pass unnoticed. In a February 1898 article in the antisemitic newspaper La Libre parole, its publisher and editor, Edouard Drumont, author of the bestseller La France juive (Jewish France), described La Revue blanche as: “This little world led by the two [sic] Polish Jewish Nathanson [sic] brothers, is made up of the young Jewish litterateurs Gustave Kahn, Romain Coolus, Lucien Muhlfeld, Fernand Gregh, Marcel Proust, Tristan Bernard, [and] Léon Blum.” Drumont called them “a handful of Jews, newly disembarked in this country whom he strangely accused of having “introduced anti-Semitism into all souls and corporations.” It was this Jewish presence, and the review’s support for causes like the defense of Alfred Dreyfus that led Drumont, the most vocal antisemite of the time, to call the magazine “an intellectual Dreyfus,” i.e., a traitor to France.

Despite Drumont’s view of the review, it at times demonstrated a certain ambiguity, if not indifference, to Jewish matters, particularly prior to the Dreyfus affair. In 1895, early in the days of the Dreyfus affair, which began the year before with the arrest for espionage of Alfred Dreyfus, La Revue blanche spoke out against attacks on the Armenians by the Turks and the repression of Spanish anarchists, but said not a word about the antisemitic riots in Algiers or of Captain Dreyfus. It is both a sign of the review’s openness but also of lack of sensitivity to Jewish issues that in 1896 it published an article in praise and in memory of the Marquis de Morès, a vocal and militant member of the Ligue anti-semitique who was killed that same year while leading a failed crusade against the Jews of North Africa. The historian of the review Paul-Henri Borrelier was right in describing the pre-Dreyfus Revue’s “uncertain combat against antisemitism.”

The very first article in La Revue blanche’s first Parisian issue in 1891 proclaimed its editors’ and publishers’ intentions for the magazine: “This is hardly a fighting review. We propose neither to undermine established literature nor to supplant the already organized young literary groups. Put simply, we want to develop our personalities.”

Whatever was said in this unsigned statement, assumed to have been written by Lucien Muhlfeld, the magazine’s editorial secretary, if ever an intellectual review was a “fighting review” in all senses of the term, it was La Revue blanche. Over the years, it less and less disguised its anarchist-tinged political colors. But it was also and most importantly, a “fighting review” on the cultural front. The editors gave room in its pages to the most groundbreaking new writers, as it had promised “undermin[ing ] established literature” and supplanting “already organized young literary groups.”

An all-but-unknown writer appeared in an 1893 issue, publishing a strange rewriting of Flaubert’s Bouvard et Pecuchet, in which Flaubert’s heroes express antisemitic sentiments. The two men speak of the Jews’ “odd practices, unintelligible vocabulary”; of how “they all have hooked noses … vile souls turned strictly to self-interest … And what is more, they formed a kind of vast secret society.” The author of the piece, Marcel Proust, explained the clear Jew-hatred by saying, “Of course, the opinions attributed to Flaubert’s two famous characters are in no way those of the author.” Though this article would appear in his book Les Plaisirs et les jours, Proust, the Natanson’s high school classmate, was not as yet living up to the potential his supporters at La Revue blanche saw in him. It was only 20 years later, in 1913 that the first volume of A la recherche du temps perdu would appear.

The Dreyfus affair radically changed La Revue blanche. As the historians Pascal Ory and Olivier Barrot wrote, “From 1898, the editorial committee of gifted minds would become the headquarters of a general staff, the site of one of the greatest human rights enterprises of world history, virtually the seat of a party, but one unlike any other since it was that of the Dreyfusards.”

La Revue blanche’s hesitation before joining the fight for the captain was common on the French left: Defending an officer was not the top priority of anti-militarists like the editors and writers at La Revue blanche. The Jewish presence on the magazine could not but have played a role in this engagement. How could it not, given the antisemitic wave the controversy unleashed across France? Even so, it was in all probability more the review’s general nonconformity that led it to this commitment to defend Dreyfus.

The magazine’s first blow in defense of Dreyfus was published in February 1898 in an article titled, “A Protest.” The review admitted its previous silence, its “abstention” from comment on “the ongoing appalling trial,” The review’s editors’ confidence in the justice system had been destroyed by the trial and verdict, and they expressed their shock that the clear evidence in support of Dreyfus’ innocence and the quality of his defenders “are no longer enough for a judicial proceeding to be judged in keeping with the elementary guarantees of fairness.” Their anger was boundless: “For the first time, not only is light not cast, but it is now forever impossible that it be cast.”

The antisemitism the case had given rise to, which included anti-Jewish riots and demonstrations, was cause for great alarm: “We protest against public opinion, duped and fantasized, which refuses to see the danger to which the booted bureaucracy exposes us.” Yet the review’s mixed attitude to Jewishness is also made clear in this defining article on their greatest political cause. Standing matters on their head, they wrote: “In this racial persecution there is a superstition like the Judaism of its origins which takes us back to the time when Jews believed in the Talmud.”

But the principal point was that “we invite to join us all those who think freely, who seek a justice rendered in keeping with the law and who, hating all forms of autocracy, accept military autocracy less than any other.”

The review published an homage to Emile Zola after the publication of his “J’Accuse,” and, in a scathing article by Lucien Herr, librarian at the Ecole normale supérieure, it broke with Maurice Barrès, the nationalist and literary figure who had until then been the spiritual guide of many of the magazine’s writers, when he came out against Dreyfus. Herr wrote angrily, directly addressing this voice of France, that “The French soul was only ever great and strong at those moments when it was welcoming and generous. You want to bury it under a paralytic stiffness in which are placed rancor and hatred.”

The great poet and essayist Charles Péguy, who would be killed in battle during World War I, decried the “universal demoralization of an entire people, ratified by the court martial in Rennes [which condemned Dreyfus] was assuredly the consummation of the crime.”

The Dreyfus affair was not the only social battle in which the Revue engaged. In 1897, across two issues, it published a remarkable “Enquete sur la Commune,” a series of brief, firsthand accounts of the great uprising of 1871 whose specter still haunted France. A century and a half later it remains one of the best accounts of that event.

The repressive legislation passed in response to the anarchist bombing wave of the early 1890s, laws which effectively banned anarchist propaganda and activity of any kind, was harshly criticized in the pages of La Revue blanche. The strongest criticism was an article signed “Un Juriste.” The author described the legislation as, “Everyone admits that these laws never should have been our laws, the laws of a republican nation, of a civilized nation, of an honest nation. They stink of tyranny, barbarism, and falsehood.” The pseudonymous author was the future three-time prime minister of France, Léon Blum.

An 1898 volume of anti-militarist articles released by the review’s book publishing arm, provocatively titled L’Armée contre la Nation (the army against the nation) would lead the minister of war to press a charge of defamation against the publishers, a charge the Natansons were able to successfully defend themselves against by claiming the book contained nothing but articles that had already been published elsewhere and not been found criminal.

By the turn of the century French intellectuals began withdrawing from the political field. Charles Péguy later described the letdown felt during and after the Dreyfus affair by lamenting that “everything begins in mysticism and ends in politics.” At the same time, the editorial staff and stable of writers at the review had turned over several times. One of its later editors, Urbain Gohier, was a barely disguised antisemite who would become an important figure on the anti-Jewish fringe. Yet the quality of the contributors was still high. If Mallarmé’s poetry no longer appeared in its pages, the young Guillaume Apollinaire did. Alfred Jarry became a regular contributor, the Revue publishing his masterpiece, Ubu Roi, as well as Octave Mirbeau’s classic Diary of a Chambermaid, serially and in book form by its Editions de la Revue blanche. That enterprise also published what is considered to be France’s first bestseller, a translation of—of all things—the Pole Henryk Sinkiewicz biblical epic Quo Vadis.

By the first years of the 20th century only one Natanson brother, Thadée, remained on the magazine. Embroiled in a lengthy divorce, he seemed to have grown tired of the magazine. It was losing money, but then, according to Thadée’s wife, later famous as Misia Sert, that had always been the case. In 1903 La Revue blanche published the last of its 237 issues. Its closing was in no way an indication of failure. It had set out to be the voice of a new France, of a more open country, both politically and culturally, and was, in the end, both its begetter and its voice.

Mitchell Abidor is a writer and translator who has published over a dozen books on French radical history.

Zawartość publikowanych artykułów i materiałów nie reprezentuje poglądów ani opinii Reunion’68,

ani też webmastera Blogu Reunion’68, chyba ze jest to wyraźnie zaznaczone.

Twoje uwagi, linki, własne artykuły lub wiadomości prześlij na adres:

webmaster@reunion68.com