„Kazania z lat gniewu” rabina Kalmana Kalonimusa Szapiry z getta warszawskiego już dostępne

„Kazania z lat gniewu” rabina Kalmana Kalonimusa Szapiry z getta warszawskiego już dostępne

Przemysław Batorski

Oddajemy w Państwa ręce kolejny tom Pełnej Edycji Archiwum Ringelbluma, zawierający wojenne kazania Kalmana Kalonimusa Szapiry – cadyka z Piaseczna. Podczas wojennych „lat gniewu”, mimo szans ucieczki, Szapiro pozostał w okupowanej Warszawie, by głosić komentarze do Tory, nauczać, opiekować się uchodźcami i głodującymi. Jego pisma należą do najważniejszych dokumentów myśli żydowskiej z okresu Holokaustu.

.

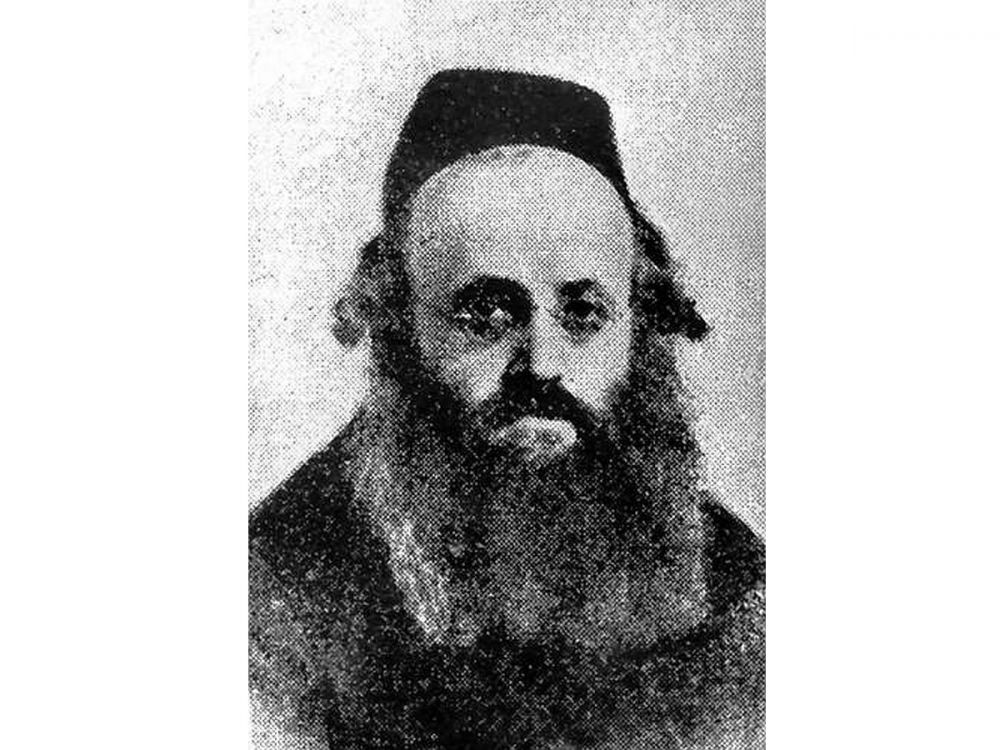

Kalman Kalonimus Szapiro

Kalman Kalonimus Szapiro

Nie porzucę swoich chasydów

Kalman Kalonimus Szapiro urodził się w 1889 r., prawdopodobnie w Grodzisku mazowieckim. Jego ojcem był 65-letni rabin Elimelech z Grodziska, który zmarł trzy lata po urodzeniu się chłopca. Szapiro wywodził się z rodu sławnych chasydzkich rabinów Elimelecha z Leżajska i Widzącego z Lublina. W 1905 r. ożenił się, a w 1908 r. został uznany cadykiem, czyli „sprawiedliwym”. W 1913 r., gdy miał zaledwie 24 lata, wybrano go na rabina Piaseczna.

Większość czasu spędzał jednak w Warszawie, gdzie założył jesziwę – szkołę chasydzkich rabinów, która w latach 30. liczyła ok. 300 studentów. Stał się znanym rabinem, reprezentował oświecony nurt chasydyzmu: „był wielkim uczonym, błyskotliwym i oryginalnym, umiejącym nowatorsko podejść do wszystkich aspektów Tory, zarówno pisanej, jak i ustnej, a także do jej wielopoziomowej interpretacji, w której wykorzystywał różnorodne źródła, od literatury zoharycznej, przez pisma Ha-Ariego aż po tworzoną w różnych okresach literaturę chasydzką”[1] – pisze Daniel Reiser. Szapiro popierał osadnictwo Żydów w Palestynie. Chociaż pisał w jidysz, dobrze znał też język polski.

Co do charakteru, „cechowały go wzorowy porządek, zamiłowanie do ceremonialności z jednoczesną skłonnością do prostoty, a także radość, wyciszenie i spokój oraz brak paraliżującego lęku przed grzechem, tak typowego w owym czasie dla innych odmian chasydyzmu”[2] – pisze Reiser. Podobnie jak inni chasydzi, komponował nigunim – melodie bez słów, nucone w okresie szabatu – i grał je na skrzypcach. Po śmierci pierwszej żony w 1937 r. zaniechał gry.

We wrześniu 1939 r., podczas ciężkich bombardowań Warszawy, Szapiro stracił syna, żonę i ciotkę. Kilka dni później z przyczyn naturalnych zmarła jego matka. W tym okresie pojawia się przerwa w kazaniach, trwająca aż do początku listopada. Napisał wtedy: „nie można [oczekiwać od] Żydów, iż zdołają znieść nadmiar cierpienia”[3].

Gdy w listopadzie 1940 r. zamknięto bramy getta warszawskiego, Szapiro nie musiał się do niego przenosić – w swoim mieszkaniu przy ulicy Dzielnej 5 pozostał do końca pobytu w „dzielnicy zamkniętej” nauczając, wygłaszając i zapisując kazania. „Nie porzucę swoich chasydów w tak trudnym czasie”[4] – powiedział, gdy organizacja Joint (amerykańska organizacja pomocy Żydom mieszkającym poza Izraelem) chciała przekazać mu paszport umożliwiający opuszczenie okupowanej Europy.

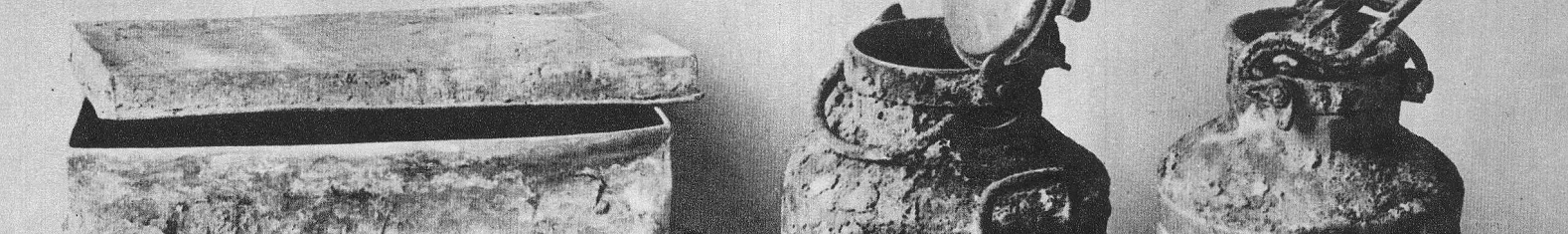

![szapiro_932510-99.jpg [379.93 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2021/5/28/6de1e4f71f1be768df21adfaa0aebe73/jpg/jhi/preview/szapiro_932510-99.jpg) Jedna z ostatnich kart rękopisu “Sobotnich kazań” rabina Szapiry, lipiec 1942 r. Widoczne liczne dopiski na marginesie. / Archiwum Ringelbluma

Jedna z ostatnich kart rękopisu “Sobotnich kazań” rabina Szapiry, lipiec 1942 r. Widoczne liczne dopiski na marginesie. / Archiwum Ringelbluma

Poddać się woli Bożej

Podczas wojny zmieniały się kazania cadyka. Przed 1939 r. często interpretował nieszczęścia, które spadają na człowieka, jako karę za grzechy. „Zgodnie ze swą koncepcją cierpienia z okresu przed Zagładą, nieszczęścia i katusze uznawał za tymczasowy dopust Boży, które jego zdaniem zsyłane są przez Boga po to, by obudzić lud Izraela i nakłonić do powrotu do Niego”[5] – pisze Reiser. Nieszczęścia były w tym ujęciu gniewem Boga za niewierność ludzi.

Jednak „kiedy cierpienia się wzmogły, a prześladowania jeszcze bardziej nasiliły, Cadyk przeanalizował ich skutki i spostrzegł się, że nie niosą one z sobą nic, co zachęcałoby lud Izraela do nawrócenia, a wręcz przeciwnie. Niewyobrażalne męczarnie jedynie osłabiły wiarę oraz życie religijne i duchowe”[6]. Dlatego „już w 5701 [1941] r. porzucił sposób postrzegania cierpienia jako kary Bożej za grzechy człowieka i zamiast tego rozwinął koncepcję wiary w Boga pomimo straszliwego bólu, ukonkretniając pogląd mędrców rabinicznych, wedle którego w okresach nieszczęść spadających na świat Bóg cierpi, a wraz z Nim cierpi Jego lud”[7].

Na początku wojny Szapiro porównywał mordy i męczarnie z rąk Niemców z wcześniejszymi, znanymi z historii epizodami prześladowań Żydów. Po doświadczeniu głodu, chorób, szykan ze strony Niemców i mordów w getcie, pierwszych informacjach o masowej zagładzie i zamordowaniu przez Niemców w 1942 r. ponad miliona Żydów w obozach śmierci, radykalnie zmienił treść swoich kazań. „W tej sytuacji życie duchowe realizuje się poprzez wyzbycie się własnego ego, przez akceptację cierpienia i poddanie się woli Bożej. Nacisk położony jest na przyjmowanie zła bez jakiejkolwiek próby jego uzasadniania. Zło jest złem, nie ma co do tego wątpliwości, i nie należy go upiększać, ubierając w religijne szaty, lecz mimo to człowiek cierpiący powinien pogodzić się z bólem, gdyż taka jest wola Boga”[8] – pisze Reiser.

W ostatnim kazaniu 18 lipca 1942 r. Szapiro pisał:

Kiedy studiowaliśmy słowa proroków i słowa błp. [błogosławionej pamięci] naszych mędrców o nieszczęściach zburzenia Świątyni, sądziliśmy, że mamy jakieś pojęcie o tych udrękach, czasem nawet nad nimi płakaliśmy. Teraz widzimy, że słuchać o nieszczęściach i oglądać je na własne oczy, a tym bardziej ich doświadczać, niechaj Miłosierny nas uchroni, to przepastna różnica, do tego stopnia, że nawet w najmniejszym stopniu nie da się ich porównać.[9]

Rękopisy

„Autor miał świadomość, że niebawem umrze, stracił już całą swoją rodzinę i cóż robił? Nanosił korekty i redagował teksty swoich kazań! A wszystko to czynił, nie mając żadnej pewności, że zostaną one w przyszłości odnalezione i że kiedykolwiek będą opublikowane”[10] – pisze Reiser. Dzięki Archiwum Ringelbluma miał nadzieję na przetrwanie swoich pism, dlatego w ostatnich miesiącach przebywania w getcie warszawskim starannie poprawiał swoje teksty, notując na marginesach drobiazgowe poprawki i adnotacje.

Bratem przyrodnim Kalonimusa Szapiry był inny rabin – Szymon Huberband, współpracownik grupy Oneg Szabat. Prawdopodobnie to dzięki Huberbandowi, który w sierpniu 1942 r. został wywieziony do Treblinki, kazania Szapiry trafiły do zbiorów Archiwum Ringelbluma. W styczniu 1943 r. zostały one zakopane wraz z innymi dokumentami z drugiej części Archiwum Ringelbluma w metalowych bańkach po mleku w piwnicy szkoły im. Borochowa przy ul. Nowolipki 68. Wydobyto je z ziemi w 1950 r.

Szapiro wiosną 1943 r. został wywieziony przez Niemców do obozu pracy w Trawnikach pod Lublinem. Działacz żydowski Adolf Berman próbował go uwolnić, jak uwolnił z tego samego obozu Emanuela Ringelbluma. Jednak Szapiro postanowił pozostać z towarzyszami do końca. Został zamordowany prawdopodobnie 3 lub 4 listopada 1943 r. podczas akcji „Erntefest” [Dożynki] – wtedy to Niemcy rozstrzelali w KL Lublin, Trawnikach i Poniatowej 42 tysiące ludzi, co było największym jednorazowym masowym mordem w niemieckich obozach podczas wojny[11].

Czytaj więcej o Kalmanie Kalonimusie Szapirze

Zobacz Kazania rabina Kalonimusa Kalmana Szapiry z lat 1939-1942 w Księgarni na Tłomackiem

Przypisy:

[1] Daniel Reiser, Wstęp do wydania krytycznego kazań Cadyka z Piaseczna z lat 5700-5702 (1939-1942), w: Archiwum Ringelbluma, t. 25a, Kazania rabina Kalonimusa Kalmana Szapiry z lat 1939-1942, wersję hebrajską opracował Daniel Reiser, tłumaczenie przygotowała i wersję polską opracowała Regina Gromacka, Wydawnictwo ŻIH, Warszawa 2020, s. XV. Podstawowe informacje o Szapiro podaję za tym wstępem.

[2] Tamże, s. XIV.

[3] Za: tamże, s. XVIII.

[4] Za: wstęp, s. XIX.

[5] Tamże, s. XXVII.

[6] Tamże.

[7] Tamże.

[8] Tamże, s. XXVIII.

[9] Kalman Kalonimus Szapiro, Kazanie na Szabat Chazon 5702 [18 lipca 1942], w: Archiwum Ringelbluma, dz. cyt., s. 304. Pisownia uproszczona. Zob.: D. Reiser, dz. cyt., s. XXV.

[10] D. Reiser, dz. cyt., s. 30.

[11] Jakub Chmielewski, „Aktion Erntefest”, portal Wirtualny Sztetl, https://sztetl.org.pl/pl/miejscowosci/l/264-lublin/104-teksty-kultury/182297-aktion-erntefest, dostęp 28.05.2021 r.

Zawartość publikowanych artykułów i materiałów nie reprezentuje poglądów ani opinii Reunion’68,

ani też webmastera Blogu Reunion’68, chyba ze jest to wyraźnie zaznaczone.

Twoje uwagi, linki, własne artykuły lub wiadomości prześlij na adres:

webmaster@reunion68.com