Spending Rosh Hashanah With a Very Hungry Caterpillar

Spending Rosh Hashanah With a Very Hungry Caterpillar

ILANA KURSHAN

What a children’s book can teach us about prayer and renewal

.

KURT HOFFMAN

KURT HOFFMAN

For as long as I can remember, a key part of my spiritual preparation for the High Holidays has been deciding which books to bring with me to shul. Of course I’ll bring my Mahzor, my High Holiday prayer book, its margins filled with penciled notes I’ve taken over the years about what to think about at various points in the service so as to deepen my concentration. But prayer has never come easily for me, and during the long High Holiday services, I often find myself in need of distraction. Over the years I have collected certain books that I think of as “shul books”—books loosely related to prayer or repentance or some other aspect of the High Holiday experience, which I read whenever I find myself in need of the sort of distraction that paradoxically improves my focus.

Ever since I became a mother, though, I am less concerned with how to distract myself in shul, and far more concerned with how distract my children. What books can I bring for my kids to read so that they are less likely to interrupt me? What books can I trust that they’ll read to themselves, instead of thrusting at me eagerly with cries of “Read it! Read it!” What books are likely to absorb them for hours on end—or at least for the 10 minutes it will take me to get through the Musaf Amidah?

Most of my kids can read to themselves now, so it is getting easier. Even my youngest daughter, still in preschool, can happily occupy herself with HaParashah, an illustrated series on the weekly Torah portion by Emily Amrusi; she can’t read the words yet, but she uses the illustrations as a guide to retell the stories to herself. “No, no, no!” she’ll shout suddenly, unaware that she is speaking aloud, as if she has cried out in her sleep at night. I turn my head in her direction. Her arms are raised in the air in a gesture of protest. I look down at the open page before her, where Isaac lies bound on the altar, and I breathe a sigh of relief alongside her.

My toddler son is more difficult. Yitzvi goes through phases with books, and these days the only book he will read is The Very Hungry Caterpillar, all day long—by the light of the moon or the light of the sun, when hungry or after a snack of two pears, when wrapped up in the cocoon of his favorite blanket or when spreading his wings to flit about the park. “Hung-ee catapilla, hung-ee catapilla,” he insists, his appetite insatiable.

No doubt I’ll bring The Very Hungry Caterpillar to shul for my son on Rosh Hashanah. His sister will sit beside him perusing the Genesis volume of HaParashah, which begins, of course, with the creation of the world. I will be chanting a refrain from the Rosh Hashanah liturgy: HaYom Harat Olam, today the world was created. My son with his very hungry caterpillar may turn the pages contentedly for a few minutes, but soon he’ll plead with me to read to him, and I’ll have no choice but to oblige, starting from the very first page.

By the light of the moon. At first the world is just darkness and potentiality—a tiny egg in a dark world illuminated only by moonlight. The world is fashioned and God creates light, but there is still no life. And then there is a sun, and the first creepy crawly things appear, and “pop”—the caterpillar emerges. On each subsequent day, the caterpillar eats more than the day before, and the pages unfold as a series of flaps that grow wider and wider—one apple, two pears, three plums … Each day follows the same formula: The caterpillar eats, but he is stilllll—I draw out the final “l,” then pause and look at Yitzvi—“Hung-ee,” he concludes, and I’ll put my finger to my lips to remind him to whisper.

Today the world was created. In the book of Genesis, each day of creation is narrated with the same repetitive formula: “God said ‘Let there be’ … And it was so … God saw it was good … And there was evening and morning.” I imagine a children’s Bible in which each day of creation appears as an increasingly wider flap: Narrow for the light and darkness, a bit wider for the firmament, wider for the creepy-crawly things, still wider for the sun and moon, nearly a whole page for all the animals. Each day, God creates more and more, but the world is still incomplete. The caterpillar is still hungry.

On the sixth day of the caterpillar’s life, his appetite peaks. Over the course of a full-color, two-page spread, the caterpillar eats every kind of food imaginable: cake, ice cream, cheese, salami, candy, pie. This explosion of bounty has its parallel on the sixth day of creation, when God makes “every kind of living creature, cattle, creeping things, and wild beasts of every kind,” as well as man, created in God’s image. God charges the man and woman to be fertile and multiply and to fill the earth. But the tiny caterpillar in the bottom right-hand corner of the page is full already. He has a stomachache, and can’t possibly eat another bite.

Then comes a period of waiting, of dormancy, of sitting still and holding tight. God sees all that He has made, and finds it very good. And the heaven and earth are completed, in all their array. What is left for the seventh day? The caterpillar builds his cocoon and remains inside for two weeks. It seems as if nothing is happening. The cocoon is large and brown and it fills the whole page—for the first time, we don’t see the caterpillar anymore, with his wide smile and big green eyes. This is a period of resting, of desisting from labor, of not doing anything at all. This is Shabbat, the day of rest, when we are supposed to imitate God and desist from the work of creation.

It seems on Shabbat like nothing is happening. If we stop creating, how could something new emerge? What could possibly come of resting and staying put, holed up in the cocoons of our homes? Quite a lot, apparently. At the end of the book, when the caterpillar emerges, he is a beautiful butterfly, his dazzling multicolored wings spread across two facing pages. All that time he was in that cocoon, new cells were forming rapidly, increasing and multiplying so that the butterfly might spread its wings and fill the earth. All that time it seemed nothing was happening, a transformation was underway.

On Rosh Hashanah we focus on who we are and who we can be. We think about the ways we have changed, and the ways we still hope to change. Often it seems like we are in the very same place as we were last year, and the year before that. If we move forward, it is ever so slowly, like a caterpillar creeping along from page to page. When will the butterfly emerge?

Sometimes when I read Yitzvi The Very Hungry Caterpillar over and over, I feel like I’m sitting in shul for a long and repetitive service. I know the book by heart and Yitzvi can complete every line, so we recite the text responsively. I chant the words in a tune that has become familiar to us both, pausing each time in the same places: “By the light of the—.” I pause, and Yitzvi bobs his head excitedly: “Moon!” I go on: “A little egg lay on a—.” Again, I pause, and Yitzvi immediately chimes in: “Leaf!” The book unfolds between us as a call-and-response, as if I am the prayer leader and he is the congregation’s most vocal member.

One day I come into Yitzvi’s room, where he has been napping all afternoon. I find him sitting up in his crib with The Very Hungry Caterpillar, reciting the book to himself. He misses a few words here and there, but he is clearly not paraphrasing; he knows the rhythm of each page, and when he doesn’t know a particular word, he replaces it with a similar sound: “By a light on ah moon, a li’l egg, on on on leaf!” It is as if the words of the book have a certain sanctity, and he knows he must remain faithful. He turns the page. He is so absorbed in the book that he doesn’t notice that I have entered, and I think of the ancient rabbis’ image of a person so immersed in prayer that he doesn’t stop even when a snake curls around his ankle. I come over to his crib and tousle his hair, and he thrusts the book at me, tugging at my sleeve: “Read it! Read it!”

The more I read the book to Yitzvi, the better I come to understand my own struggles with prayer. The traditional Jewish liturgy is largely fixed and unvarying, with the same prayers recited every day of the week, and additional prayers for the Sabbath, holidays, and High Holidays. The challenge of prayer is to find meaning in reciting the same words day after day. Our prayers are not supposed to be rote; we are supposed to pray to God from the fullness of our hearts, bringing our fears and hopes to bear. How is this possible when each day we open to the same page and begin with the very same words thanking God for the gift of waking up in the morning: “I am grateful to You, O living and sustaining King, for restoring my soul to my body.”

Often it seems like we are in the very same place as we were last year, and the year before that. If we move forward, it is ever so slowly, like a caterpillar creeping along from page to page. When will the butterfly emerge?

Sometimes I try to pay attention to how the words speak to me differently today, in this time, in this place. Why am I especially grateful to have woken up today of all days? Was there reason to think I might not have woken up on this particular morning? Ideally the liturgy becomes a script we act out, each time infusing the words with new resonance, new significance, a new emotional valence. “Lord, guard my lips from evil and my tongue from lies. Help me ignore those who slander me.” What are the evil lies I am concerned about speaking on this particular morning? Who might wish to slander me, and why? The liturgy prompts the same questions in me day after day, but my responses are rarely the same.

And yet the purpose of prayer is not to arrive at answers to these questions. Prayer is not an intellectual exercise, but an act of devotion. I don’t understand every word in the prayer book, but the liturgy nonetheless has a comfortable familiarity. When I pray, my focus is less on the meaning of the words than on the experience of reciting them over and over again.

Does Yitzvi know what a cocoon is? A stomachache? He would never stop to ask me what a word means, because for him, meaning is largely irrelevant to the ritualized experience of reading. He wants to hear the story not to find out what happens, but to be transported by its rhythms, to lose himself in the phrases that have become intimately familiar even if they elude comprehension. By the end of the book, he will be in a different place, just as we are ideally in a different place after each time we pray. We may think, in the beginning, that we cannot bear to read the book another time. And yet each time we finish and emerge from the cocoon of our prayer shawls, we are transformed. Our prayers today are different from the day before; our prayers this new year are different from the year that passed. Perhaps The Very Hungry Caterpillar is a shul book after all.

Ideally our prayer is not just an occasion for transformation, but also a means of connection. The rabbis of the Talmud credit the forefathers in the book of Genesis—Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob—with the establishment of the daily prayer services. Abraham instituted the morning prayer when he prayed on behalf of Sodom; Isaac instituted the afternoon prayer when he went out to the field in the late afternoon; and Jacob instituted the evening prayer when he dreamt of a ladder of angels. None of these individuals was reciting a fixed liturgy; they were talking to God. In its most fundamental sense, prayer was, and is, a means of communication. The point is not the words spoken or the text recited, but the connection forged.

When I reread the same book to Yitzvi countless times, I challenge myself to view the fixed, unvarying text as a springboard for connection. I look into my son’s animated eyes as we come to his favorite page, on which the caterpillar eats the cake and the ice cream and the pickle, and each time, unfailingly, “He was still hungry.” Yitzvi never gets bored of the refrain. He is delighted each time anew. The phrase “His graciousness endures forever” repeats 26 times in Psalm 136, which is recited every morning. I marvel to think that God’s patience could be as enduring as God’s graciousness. Does God never tire of our prayers? Is God still hungry for more?

The Talmudic rabbis note a subtle inconsistency in the Bible’s description of the creation of the world. Although grass was created on the third day of creation, it did not emerge from the earth until the sixth day, when we are told, at least initially, that “no shrub of the field was yet on the earth” (2:5). The rabbis explain that for three days, the grass stood poised beneath the surface of the earth, waiting to grow until Adam came and prayed for it to emerge. According to the Talmud, “God desires the prayers of the righteous,” and thus aspects of the creation of the world were contingent upon human prayer. God created an imperfect world so that human beings would have reason to call out to God.

In some ways praying is easier with little children to distract me. I no longer read to distract myself in shul, but instead seek out every opportunity to focus on the prayer book. But my concentration wavers nonetheless. If only I could recite my prayers with the same eagerness and devotion with which God receives them. If only I could read to my child with the same excitement the words seem to awaken within him. “Again, again!” Yitzvi insists when we turn the final page. He wants me to keep rereading, even if we’re in shul, and even if it’s Rosh Hashanah morning. Today the world was created. No sooner has the caterpillar become a beautiful butterfly than Yitzvi wants to turn back time, starting all over with the egg on the leaf. I summon my patience and return to the first page, to the beginning, creating the world anew.

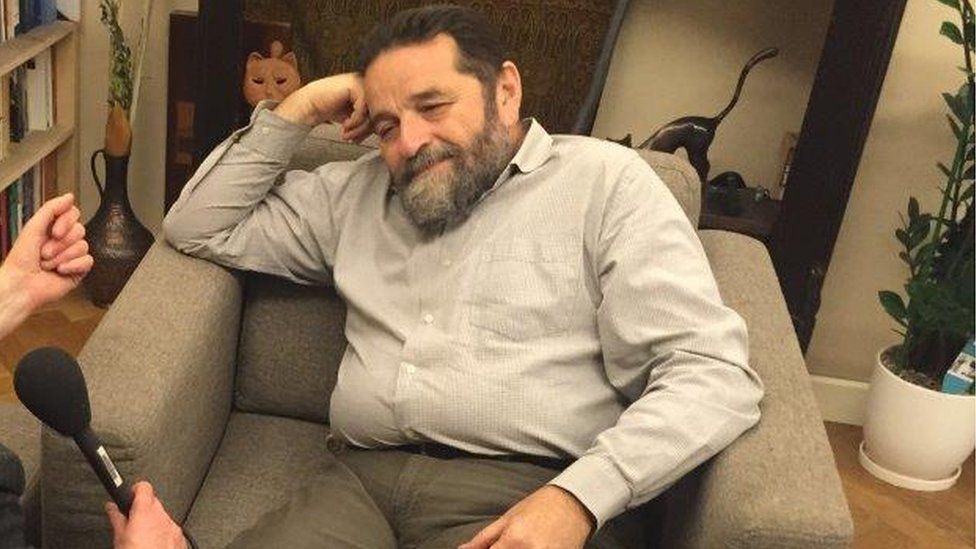

Ilana Kurshan is the author of If All the Seas Were Ink.

Zawartość publikowanych artykułów i materiałów nie reprezentuje poglądów ani opinii Reunion’68,

ani też webmastera Blogu Reunion’68, chyba ze jest to wyraźnie zaznaczone.

Twoje uwagi, linki, własne artykuły lub wiadomości prześlij na adres:

webmaster@reunion68.com

foto: BBC

foto: BBC