The Other History of the Holocaust

The Other History of the Holocaust

Alex Zeldin

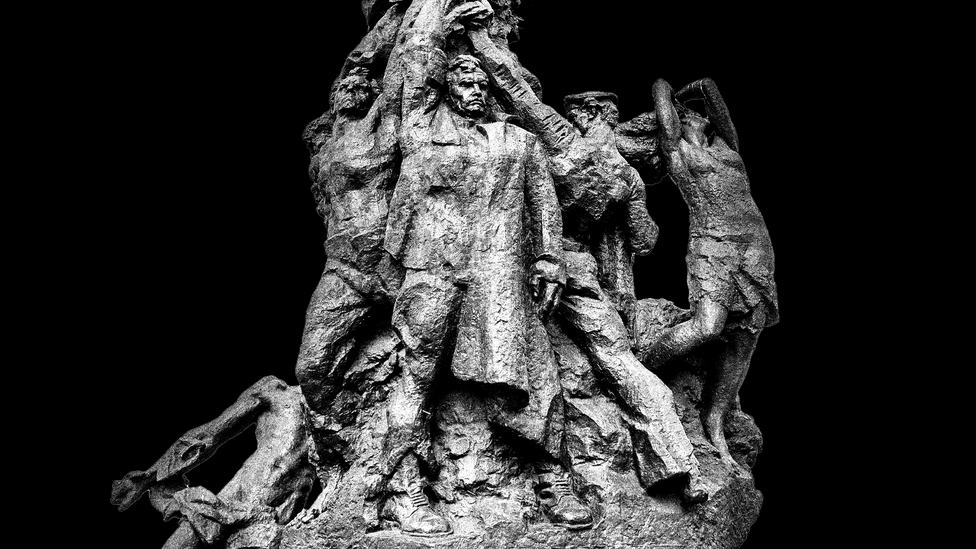

A monument to people killed by Nazis in Babyn Yar, Kyiv, Ukraine (Getty; The Atlantic)

A monument to people killed by Nazis in Babyn Yar, Kyiv, Ukraine (Getty; The Atlantic)

Picture a long table covered end to end in crystal bowls filled with cured fish, pickled foods, and salads with an alarming amount of mayonnaise. There’s vodka and black bread on the table too. A man stands up and shouts “Anecdote!”—a common Russian way of announcing a forthcoming joke—and, with a shot of vodka in hand, begins to tell of a conversation in the Soviet Union.

“Comrade Rabinovich, why are you applying for an exit visa to Israel?” asks the Soviet official. “We have built an amazing worker’s paradise!”

“Well, comrade, there are two reasons,” says Rabinovich. “The first is that every night my neighbor comes to my door, drunk and filled with salo, banging and screaming that after they get rid of the Communists, they’re coming for the Jews.”

“But they will never get rid of the Communists,” declares the Soviet official.

“You’re right! Of course you’re right,” says Rabinovich. “That’s the second reason!”

I know this joke, and countless others like it, because like many other Jewish refugees from the Soviet Union, I heard them told repeatedly over the years in the great hall of Russian-speaking Jewish learning: the dinner table. Meals with family and trusted friends were where I learned comedy. These meals with their elaborate vodka toasts, zakuski, and subversive jokes were where I learned about the conquests of Peter the Great, where I saw my friends recite Pushkin poems from memory and be applauded by the beaming adults. I learned about great-power politics, and, more subtly, the difference between vlast i narod—the government and the people. At those meals I learned about the Great Patriotic War and all of our family members who were not sitting there with us because they had died during it. These meals were where I was taught how my parents and our community understood the world and an oral history of what our family had experienced.

I knew when the lessons were serious, because my mother would deliver them in a hushed tone. One time while she was preparing a meal, she quietly told me the importance of knowing which of my neighbors to trust on the basis of how they felt about Jews. I learned this in New Jersey in the ’90s. That understanding of Eastern European history and the attitudes that formed with it have been, surprisingly, showing up in international headlines quite a bit recently; Russian President Vladimir Putin has declared that “de-Nazification” is the objective of his country’s “special operation” in Ukraine, and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky has invoked the Holocaust in his appeals to Western audiences, particularly the Israeli government, for support in Ukraine’s struggle.

I have not put the worldview my parents taught me to much use in the United States in the decades since. It did, however, teach me that I had a different understanding of things than those around me, even other Jewish communities. American films about the Holocaust and World War II felt like a portal into a different dimension’s history. Nobody in my family who survived the war had numbers tattooed on their arm. Nobody in my family, as far as I was told, died in a labor or death camp. The stories were always about young men who bravely fought and died in the Red Army, and about women, children, and the elderly who, after being evacuated from their homes, came back to rubble and the reality of never seeing their loved ones again. What happened to the people who were not in the army and did not evacuate? I was vaguely told that they had died during the course of the war, with dark hints that Nazi collaborators among their neighbors had helped make that happen. The Nazis were not understood by postwar generations of Soviets to be motivated by hatred of Jews; they were understood to be anti-Soviet and specifically anti-Russian. The vocabulary of Holocaust and genocide to describe what happened to Jews specifically would come later for me, with exposure to Western media and ideas.

When I talked with American Jews whose parents or grandparents had survived the Holocaust, or with survivors themselves, what they described was similar, yet different. They would call it a genocide. They would describe Jews specifically being targeted for destruction. They would talk about camps and the strategies that the Jews in them used to get an extra ration of food to survive. They would tell the stories of their loved ones who died in horrific ways in these labor and death camps. Until I studied it in an academic environment, I did not understand that my family members perished in the same Holocaust as theirs. The Soviet Jews in my family who survived the Holocaust never once referred to themselves as Holocaust survivors—when we were exposed to Western films about this in the ’90s, my family would say the Holocaust was something that the Jews who went through the camps survived.

How could our understandings be so different? An estimated 2 million of the 6 million Jews murdered in the Holocaust were Soviet Jews. I was able to reconcile the two narratives only when I learned of what Western scholars refer to as the Holocaust by bullets—the version of the Holocaust that played out in the Soviet Union (which includes present-day Ukraine), where mass shootings, not death camps, were the predominant means of extermination. I also studied how the Soviet Union memorialized the war in the years and decades after—downplaying in formal education and the media the reasons Jews had been murdered. The truth was not just that Jews happened to have been killed by Nazis and Jew-hating collaborators; what they experienced was a deliberate and state-sponsored form of genocide. The 33,771 human beings who were massacred over two days at a ravine outside Kyiv were not simply “victims of fascism,” as the Soviet government taught its people to think of civilians who died during the war; they were murdered because they were Jews, in the same campaign of extermination that spanned the entire continent. Though years would pass before it became doctrine, the Soviet policy of obscuring the fact that the Nazis were targeting Jews began before the war was even over.

Soviet Jews who survived the war knew that their loved ones had been murdered because of their Jewish ethnicity. They knew that some of their neighbors were Nazi collaborators. The Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee (JAC), partly composed of Soviet Jews who had traveled abroad to raise huge sums of money for the Soviet war effort, went to great lengths to document Nazi atrocities in the Soviet Union in the Black Book.

As the war ended and Joseph Stalin’s government shifted its domestic and foreign policy, a campaign against “Jewish nationalism” and “cosmopolitanism” and “Zionism” began to be waged against Soviet Jews, reaching its climax with the Doctor’s Plot, a conspiracy theory promoted by Stalin’s government claiming that “Zionists” and people with Jewish surnames were attempting to assassinate Soviet officials. The Black Book was suppressed in the Soviet Union in 1947, and many members of the JAC were executed by Stalin’s regime during the height of his anti-Jewish panic. The facts that the committee had methodically documented, including widespread Nazi collaboration by ethnic Ukrainians, Latvians, and others, undermined Soviet propaganda, which claimed uniform support for the Stalinist regime from all Soviet citizens. Jews attempting to put up memorials for their loved ones were punished, their actions characterized as “Jewish particularism”; their recollection of the war didn’t serve the Soviet regime’s interests. The interests of the vlast were not the same as those of the narod, at least the Jewish one.

As a result, the children and grandchildren of Soviet citizens who survived the war did not know that Jews experienced a distinct policy of extermination under Nazi occupation. This was an effective form of Holocaust denial, because it contained a great many truths that lived experience validated: What family in Eastern Europe came out of the war without having lost loved ones? Estimates vary, but approximately 8 million Soviet soldiers, including more than 120,000 Jews, died in the war, and 20 million civilians, including those 2 million Soviet Jewish civilians, died under Nazi occupation.

Every Soviet citizen who grew up in the shadow of the Great Patriotic War was taught in school and by the media how much the entire nation suffered, and nearly every Eastern European Soviet family had personal stories of unimaginable loss to accompany that formal education. Soviet estimates are that Russians suffered the most losses in absolute terms of any part of the Soviet Union under Nazi rule. It was also important for the Soviet regime, particularly under Stalin, an ethnic Georgian, to cultivate the support of Russians in order to maintain its legitimacy. Chauvinistic pandering to ethnic Russians, their language, and their sensibilities manifested in many ways throughout the Soviet period.

This Soviet understanding of the war and of Holocaust memory is receiving new attention amid the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Many Western observers looked on incredulously as Putin attempted to justify his invasion of Ukraine on the grounds of “de-Nazification.” De-Nazify a country with a Jewish leader? To Russians, given their understanding of the Great Patriotic War, de-Nazifying a country led by a Jew does not sound so ridiculous. However, the Russians are not alone in retaining this incomplete understanding of what happened on Soviet territory during the Second World War. Recently, Zelensky, a Jew whose Soviet ancestors died in the Holocaust or while serving in the Red Army, revealed a similar view during a speech to Israel’s Parliament, the Knesset.

Zelensky appealed to the ties between Ukraine and the Jewish people, quoting former Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir, who was born in Ukraine, to describe his country’s existential struggle with Russia. He reminded Israelis of the hundreds of Ukrainians who were honored by Yad Vashem, Israel’s national Holocaust memorial and research center, for saving Jews during the Holocaust. Zelensky painted this not as a pained and complex history (omitting, for example, why Golda Meir left Ukraine), but as one of consistent mutual solidarity. This is not an understanding shared by Jews outside the Soviet Union, and especially not in Israel, many of whose founders fled the ethnic violence of Central and Eastern Europe to establish a country where they could be included as full citizens. Zelensky’s speech to the Knesset was received, as one colleague who covers Israeli politics put it to me, “like a fart in church.” Many Israeli politicians were not happy, feeling that the Ukrainian leader had downplayed Ukrainian collaboration with the Nazis.

Soon after, Zelensky gave an interview to Fareed Zakaria on CNN. Among other topics discussed, Zakaria asked Zelensky for his thoughts, given his status as a Jew, on Russia’s stated need to de-Nazify Ukraine. Zelensky in his reply opted to focus on Putin’s access to accurate information and the Russian president’s mental well-being.

Zakaria pressed on and asked Zelensky to talk about his grandfather who survived the Holocaust and the war, and what lessons Zelensky had learned from that family history. Zelensky described his family story in a way that was immediately familiar to every Jew from the former Soviet Union: His grandfather and his four brothers served in the Red Army. His grandfather was the only one to survive the war. His grandfather’s parents were killed by the Nazis, who set their village ablaze, an experience that was familiar to Jews and non-Jews alike in occupied Ukraine. “When Russians are telling about neo-Nazis and they turn to me, I just reply that I have lost my entire family in the war, because all of them were exterminated in World War II.” He went on to talk about the Nazi occupation of Ukraine and its parallels to what the Russians are subjecting Ukrainians to today.

In the interview, Zelensky never said the words Holocaust or Jew. Yet, like many other former Soviet Jews, Zelensky no doubt knows that the civilians in his family were murdered because they were Jewish. But his framing is different, thanks to the multiple generations of Soviet propaganda that he and every other former Soviet have been subjected to.

The intellectual framework surrounding the Second World War that the Soviet regime forced upon its citizens, Jewish and non-Jewish alike, did not account for why the Nazis targeted the Jews in particular. Far from being a Holocaust denier who downplays Ukrainian Nazi collaboration, Zelensky is, like the rest of the 2 million Jews who survived Soviet rule, making political appeals using what he knows—or, put more pointedly, what he has been allowed to know.

About the author: Alex Zeldin is a contributing columnist for The Forward. He has written for Tablet Magazine and The Washington Post.

Zawartość publikowanych artykułów i materiałów nie reprezentuje poglądów ani opinii Reunion’68,

ani też webmastera Blogu Reunion’68, chyba ze jest to wyraźnie zaznaczone.

Twoje uwagi, linki, własne artykuły lub wiadomości prześlij na adres:

webmaster@reunion68.com