The Warsaw Ghetto Revolt was initially dubbed ‘fake news’ by some US Jews

The Warsaw Ghetto Revolt was initially dubbed ‘fake news’ by some US Jews

MATT LEBOVIC

New book ‘The Jewish Heroes of Warsaw’ traces the immediate aftermath of Holocaust’s most famous revolt, including the ‘gendering’ of resistance and politicization of its narrative

Jews marched out of the ghetto during Warsaw Ghetto Revolt in April and May, 1943 (public domain)

Jews marched out of the ghetto during Warsaw Ghetto Revolt in April and May, 1943 (public domain)

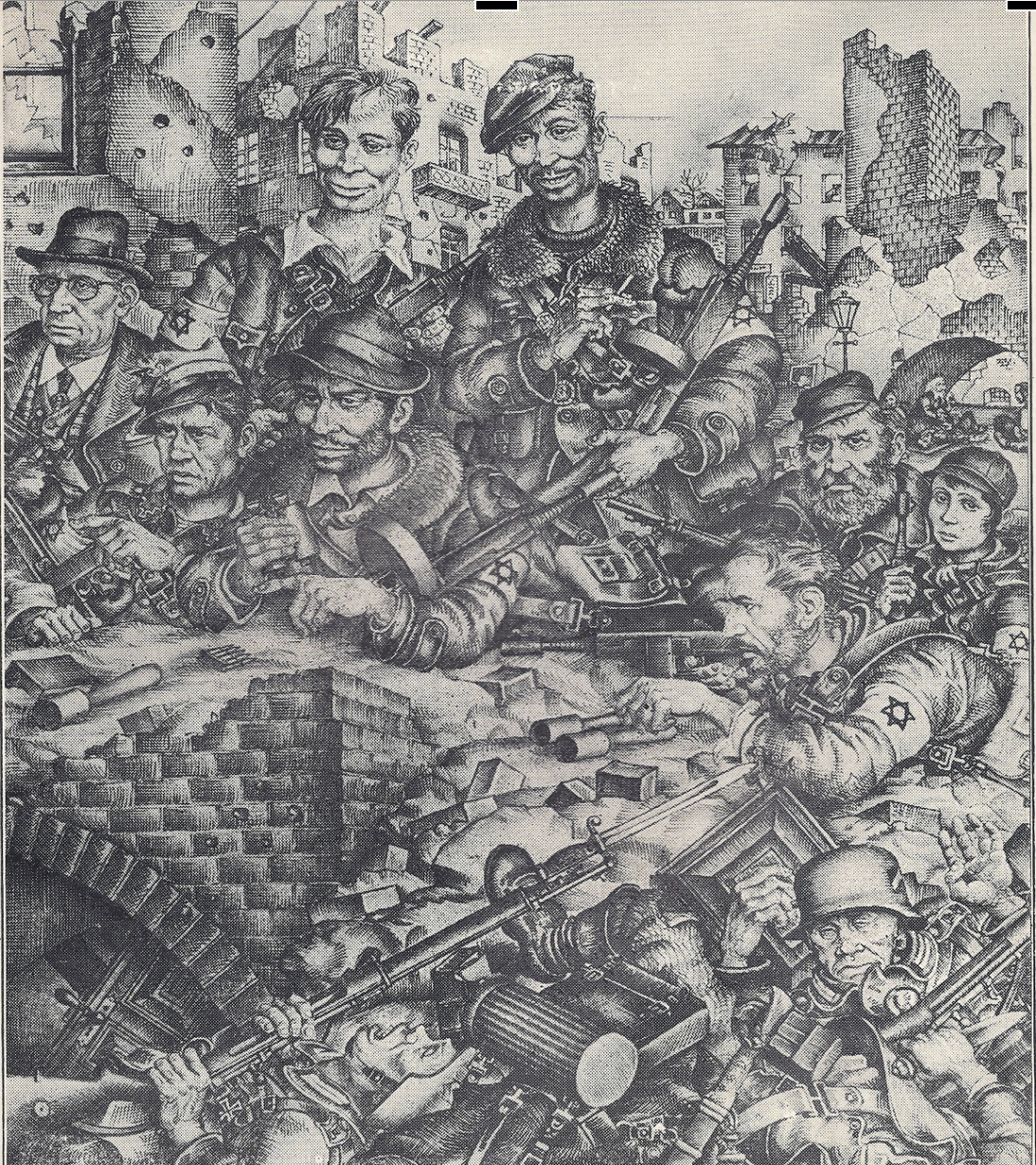

When American political cartoonist Arthur Szyk decided to commemorate the one-year anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Revolt, he crafted a montage dedicated to “the heroic battle of our brothers in the war against the Nazi barbarians,” as the caption read.

The image showed a cross-section of Warsaw Jews fighting against a Nazi war machine intent on burning the ghetto to the ground. Most of the ghetto’s 400,000 Jews had already been deported to the death camp Treblinka in 1942, and about 800 people — most of them young adults — participated in armed resistance the following year.

Although Szyk knew that women were involved in the revolt, no woman appeared in his widely circulated image. There were boys with side-curls and men in workers’ caps, as well as resisters with symbols nodding to socialism, Zionism, and Polish nationalism — just no women.

“The memory of the revolt and memory of resistance does end up being very gendered,” said historian Avinoam Patt, whose book — “The Jewish Heroes of Warsaw: The Afterlife of the Revolt” — will be published on May 4.

Among ways in which the revolt was “edited” for American audiences, said Patt, was a “specific type of heroic image that privileged masculine fighters as leaders of the resistance while presenting women as symbols of martyrdom and sacrifice,” he told The Times of Israel in an interview.

In his book, Patt explores the revolt’s immediate afterlife, when Jewish communities began to “process” what took place and shape narratives that still endure. For example, Patt demonstrates how the revolt was memorialized in Israel to enforce Zionist ideology, while American Jews generally framed the revolt as part of Allied war efforts.

“The book looks at the interplay of history and memory,” said Patt, director of the Center for Judaic Studies at the University of Connecticut.

Arthur Szyk’s commemorative montage of the Warsaw Ghetto Revolt (public domain)

Arthur Szyk’s commemorative montage of the Warsaw Ghetto Revolt (public domain)

When the Warsaw Ghetto Revolt broke out on April 19, 1943, Jews around the world were sitting down for the Passover seder. By this point in the war, it was widely known that millions of Jews were being murdered across Europe. However, in the United States, American Jewish leaders had been unable to catalyze large-scale rescue actions.

News of the revolt hit just as people were shifting from “active rescue efforts” to “memorial mode,” said Patt, and not everyone in the US believed a revolt had taken place.

Historian Avinoam Patt (courtesy)

For example, New York’s influential “Der Tog” would not confirm an uprising took place until May 12. In an editorial, the Yiddish newspaper said the revolt was likely a German “pretext” to conduct a massacre, and that unarmed Jews were not able to hold off an army that devoured Poland in four weeks.

Apart from the stance of “Der Tog,” however, the American Jewish press generally picked up the story. For example, “The Forward” printed a front-page story about the revolt on April 23, just four days after the outbreak of fighting.

In both the US and Israel, media outlets erroneously reported that “Polish commandos” had infiltrated the ghetto to help lead fighting. In fact, no such commandos participated, and the ghetto’s Jewish Fighting Organization managed to obtain only a few weapons from Polish resistance leaders.

‘A revolution in Jewish history’

As Jews slowly learned the identities of Warsaw Ghetto Revolt fighters, fictionalized accounts began to appear. In the Yiddish play, “The Battle of the Warsaw Ghetto,” the heroes were fictionalized to meet the needs of a dramatic NBC radio production, for example.

“In the American context, the identities of the heroes seemed less important,” said Patt. “For Zionist leaders in the Yishuv, the names matter greatly, as they did for Bundists in New York and elsewhere,” he said.

For American Jews, the revolt was most important as a symbol of Jews’ contribution to the Allied war effort, said Patt. The fictionalization of the revolt endured for decades, including the seminal 1961 book, “Mila 18,” by Leon Uris.

Warsaw Ghetto footbridge connecting cut-off parts of the ghetto from Aryan Warsaw under Nazi occupation (public domain)

Warsaw Ghetto footbridge connecting cut-off parts of the ghetto from Aryan Warsaw under Nazi occupation (public domain)

“The revolt was interpreted differently by different groups of Jews,” said Patt. “Current social and political agendas shape how history is recorded,” he said.

During the months following the revolt, a public relations battle was waged behind the scenes. Specifically, Zionist leaders were alarmed that Bundist leaders were claiming credit for what took place in Warsaw.

In May 1944, several Zionist leaders hiding in Aryan Warsaw compiled accounts of the revolt from all fighting sectors of the ghetto. The document trove was sent to London, and the name Mordechai Anielewicz — the revolt’s 24-year old leader — entered into Zionist and Jewish history.

Zivia Lubetkin (public domain)

Zivia Lubetkin (public domain)

When Zionist leaders compiled their 120-pages of testimony, they made sure to elevate the movement’s role in unifying resistance movements across the ghettos. The narrative that only Jews can protect themselves contrasted — for example — with the Bundists’ emphasis on Jewish-Polish cooperation.

In Israel, the revolt came to be seen as “a revolution in Jewish history.” The uprising’s first day became an “anchor” for Yom HaShoah and the creation of Yad Vashem, as well as the resistance-oriented nature of Israeli Holocaust memory in general.

One of the “Jewish heroes of Warsaw” featured in Patt’s book is Zivia Lubetkin, whose eight-hour speech about the revolt sent shockwaves through pre-state Israel in June 1946. Along with other former resisters, Lubetkin founded the Ghetto Fighters’ Kibbutz in 1949 to commemorate that chapter of Jewish history.

Still, Patt notes, while certain names of Jewish heroes would be recorded by history, others would fade from collective memory, along with the experiences of the Jewish masses who constituted the bulk of the population in the ghetto.

Baking matzah in the Warsaw Ghetto, Nazi-occupied Poland (Courtesy: Yad Vashem Photo Archives 24DO6)

Baking matzah in the Warsaw Ghetto, Nazi-occupied Poland (Courtesy: Yad Vashem Photo Archives 24DO6)

“The symbolic spirit that animated the fighters would be more important than the identities of the actual fighters themselves, just as political interpretations that reinforced the existing worldviews of Jews in Israel and America would matter more than the complexities of wartime behavior that led to the revolt,” said Patt.

“Historians would seek to record the names of heroes in the ghetto; memory only demanded that the Jewish people remember that those heroes had fought for Jewish honor and dignity,” added the historian.

Zawartość publikowanych artykułów i materiałów nie reprezentuje poglądów ani opinii Reunion’68,

ani też webmastera Blogu Reunion’68, chyba ze jest to wyraźnie zaznaczone.

Twoje uwagi, linki, własne artykuły lub wiadomości prześlij na adres:

webmaster@reunion68.com