Living on a Prayer

Living on a Prayer

LIEL LEIBOVITZ

Why praying is the only New Year’s resolution you need

.

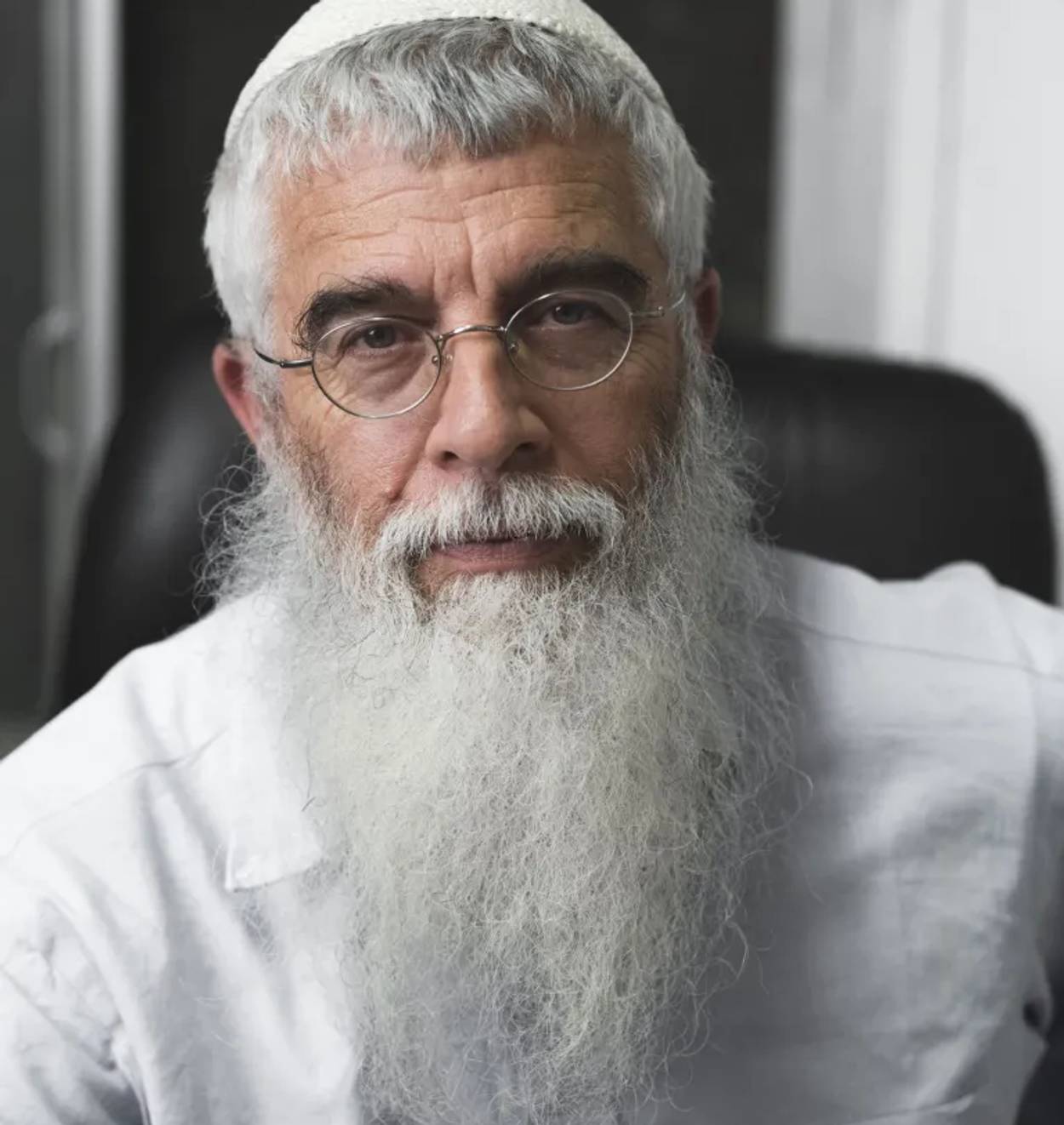

COURTESY OF DOV SINGER

COURTESY OF DOV SINGER

Men, went my grandmother’s favorite saying, make plans while God laughs.

These days, it sure seems like the Almighty is in the mood for a good side-splitter, more Monty Python than a knock-knock joke. Deadly viruses and deadly storms, political chaos and economic insecurity, and no fewer than 41 Hallmark Christmas movies—the signs of some merry apocalypse are upon us, so ornate and bizarre that they defy rational human explanation. What to do? How to bear the pain? What to resolve as 2021 gives way to 2022, when the very idea of resolutions—predicated, as it is, on a faint belief in human agency, in our own ability to shape reality—seems, in light of all the cosmic chaos, absurd?

The answer is simple: pray.

For most of my adult life, the word itself was slightly offensive. Pray, I thought, is what you did when you gave up hope, when you no longer believed in personal responsibility, when you resigned yourself to luck or fate or whatever force you believed really ran the show. Only the weak prayed, whereas the strong did. Besides, the very idea—talking to God—struck me as so preposterous as to almost defy comprehension. What do you say to a Being that has everything? And if He hast indeed, as Psalm 139 daintily assures us, searched me, and known me, and art acquainted with all my ways, why chat? Even if I could find the words, doesn’t HaShem know them already? Isn’t he the one putting them in my mouth? Why this act of celestial ventriloquism?

Judaism, in its infinite wisdom, knows that there are no good answers to these questions, because the immense and life-changing comfort that prayer provides is open only to those who do, not to those who theorize. Like skydiving, say, or sex, prayer is a participatory experience; to try and capture its pleasures from without is silly. Six years into davening thrice daily, I can report that nothing injects your day with meaning quite like beginning it with an intimate conversation with your Creator, giving thanks for another shot at trying and failing at life, but failing a little bit better. Nothing breaks up the workday like replacing that early afternoon shot of espresso with mincha, the midday prayer, checking in with the Boss up above for a lovely little boost. And nothing caps the evening like a quick, final check-in, asking God for good counsel, protection, and all the mercy we could possibly need.

If this all strikes you as flowery, a middle-age man grasping at a dab of comfort as the world around him spins out of control, it’s because any one man’s individual experience with prayer is intimate, subjective, elusive, and, ultimately, indescribable.

And that, argues Rabbi Dov Singer, is precisely the point: We aren’t, he writes in his brilliant new book, Prepare My Prayer, Homo sapiens, or Man who Knows, at all; we’re Homo mitpalelot, the latter word being Hebrew—Man who Prays. “There is a constant call,” he writes, “a longing inside people, that whispers to them in waves of ebb and flow. Pleas, desires, requests, words of gratitude. Many times in a person’s life, consciously or not, we stand before. Asking for our lives, yearning, desiring.” Prayer, in other words, isn’t some awkward practice, or a stricture, or a tradition, or a pastime: It’s the very essence of human nature.

The head of Makor Chaim Yeshiva in Gush Etzion, Israel, Singer is one of the most thrilling, original, and moving thinkers and teachers working today. Himself a student of rabbinic eminences like the late Adin Steinsaltz, Singer is deeply committed to his masters’ Hasidic revival, a religious project that is focused on cultivating a more personal relationship with God, and on understanding that this relationship, wildly uneven and intricate and mysterious as it is, must by definition comprise hesitations and revelations, long bouts of doubt followed by short bursts of joy, and, above all, questions, reams of questions we can never answer but are never permitted to stop asking.

Naturally, then, it is to prayer that Rav Singer directed his attention, leading anything from group prayer circles—watch one, and you’ll soon see strangers deprived of spiritual uplift embracing each other and weeping openly in relief—to an online prayer tutorial, available here.

If you’re looking for some practice to embrace in the new year, some succor amid the turmoil, some connection to an urge that thrums softly inside you, eager for attention but unable to find the words to express itself, you may want to give Singer’s approach to prayer a shot. Too much description, again, does it an injustice, but here he is in one of the tutorial’s first videos, musing on the very first words every Jew is commanded to say as soon as he or she wakes up: Modeh Ani (or, for women, Modah Ani).

What do they mean? One simple translation would be simply this: I give thanks. It is, Singer explains, a twinkle in his eye, a moment of childlike wonder: Wow! Look at all this stuff before me, the entire world and everything in it, and it’s all mine to explore. But dive a bit deeper—prayer is an invitation to do nothing but—and you’ll find another layer. Modeh (or Modah) also means “I confess,” or “I admit.” Prayer, Singer reminds us, cannot begin before you come to terms with reality itself, particularly those parts of it that have to do with you, especially those parts of you that are far from perfect and that you wish to amend or improve. It’s not about asking Papa in the heavens for magic; it’s about taking a good look within first, understanding precisely what must be corrected, and realizing that while God is there as a partner, most of the work has to be done by us.

Singer, thankfully, is a superb foreman. He reminds us that while the prayers are fixed and unchangeable—prayer isn’t a therapy session or a slam poetry jam, and involves words unchanged for millennia and containing immense structural and mystical wisdom—it’s incumbent upon us to make them new, make them our own. The point, he reminds us in one of the book’s short aphorisms, is

To bring the ancient words inside,

To say them again—alive, fresh, renewed.

To speak to God with an open heart, with warmth,

With wonder and emotion,

To reveal the movement from which the words were born,

Before they were expressed,

Before they were written.

It’s easier said than done, which is why Singer insists that you do it, writing your own version of Judaism’s prayers, not a substitute but a meditation, a sublimation, and, eventually, a transformation. Once the ancient words become your own, once you understand the brilliant interplay in prayer—first gratitude, then pleas, a dynamic anyone who has ever asked for a raise or a day off grasps all too well—it becomes much less baffling and much more rewarding.

So once you’ve sipped on that bubbly and Auld Lang Syned, feel free to skip those promises about losing 10 pounds or spending more time at the gym. It’s closed anyway, but your heart isn’t. Your heart still yearns for something better, because that is what hearts were designed to do. No matter who or what you believe did the designing, prayer is the exercise you need. As a wise rabbinic dictum put it long ago, just do it.

Liel Leibovitz is a senior writer for Tablet Magazine and a host of the Unorthodox podcast.

Zawartość publikowanych artykułów i materiałów nie reprezentuje poglądów ani opinii Reunion’68,

ani też webmastera Blogu Reunion’68, chyba ze jest to wyraźnie zaznaczone.

Twoje uwagi, linki, własne artykuły lub wiadomości prześlij na adres:

webmaster@reunion68.com