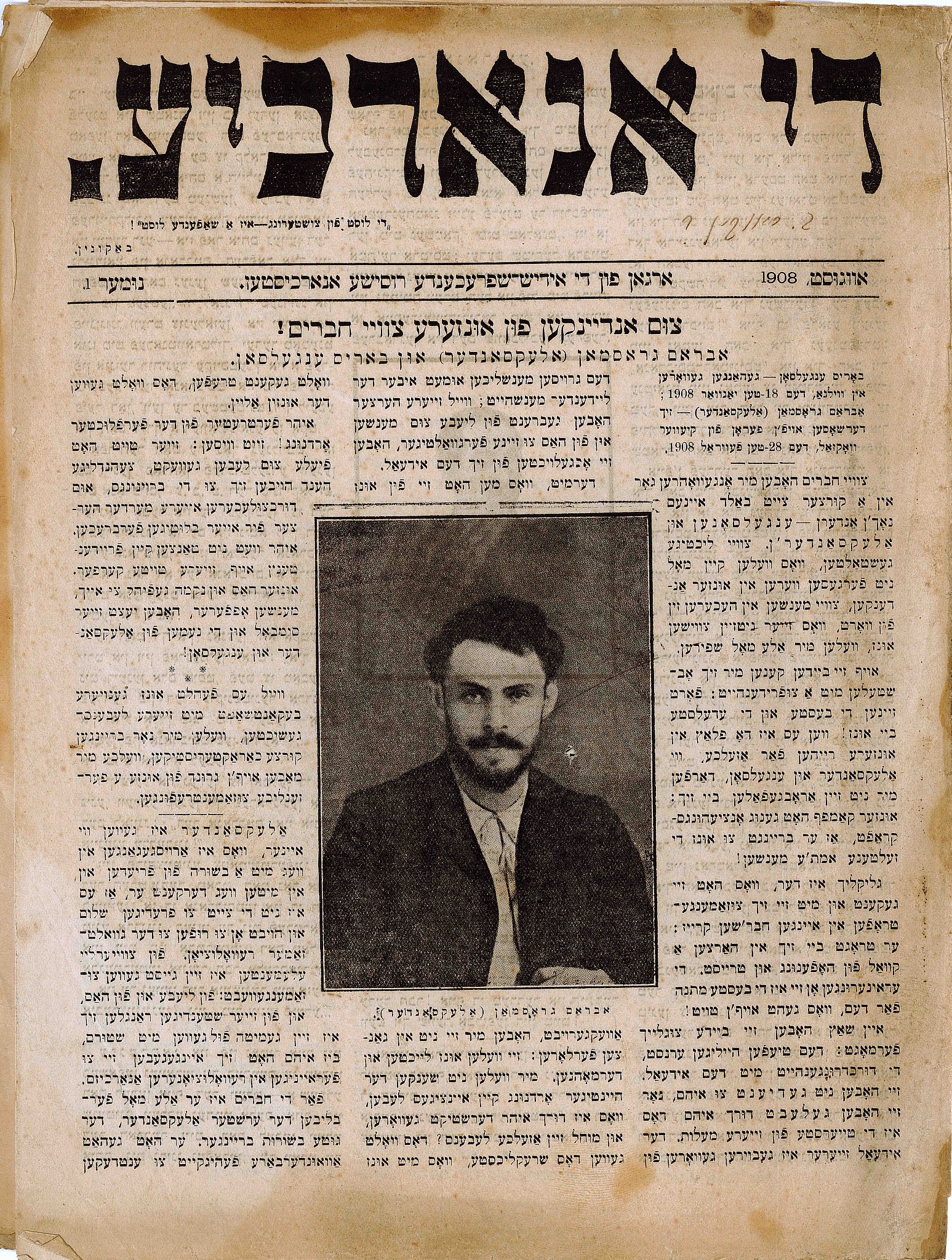

A forgotten chapter: When Jewish America spoke Yiddish — and was anarchist

A forgotten chapter: When Jewish America spoke Yiddish — and was anarchist

GIDEON GRUDO

A January 20 conference hosted by the YIVO Institute covers a seldom-recognized piece of US Jewry’s immigrant experience — and one that may serve a marginalized sector today

A group of anarchists in Warsaw mourn during the 1926 funeral of activist ‘White Morits,’ who had previously been imprisoned for anarchist activities. (Courtesy YIVO Institute for Jewish Research)

A group of anarchists in Warsaw mourn during the 1926 funeral of activist ‘White Morits,’ who had previously been imprisoned for anarchist activities. (Courtesy YIVO Institute for Jewish Research)

NEW YORK — Spencer Sunshine describes himself as an “extraparliamentary radical leftist” and/or a “libertarian socialist.” Having “known and worked on political projects with anarchists for many decades,” he explained that when it comes to anarchism, there is no one size fits all.

Sunshine, who doesn’t speak Yiddish, is the co-organizer of a January 20 conference, “Yiddish Anarchism: New Scholarship on a Forgotten Tradition” at New York’s YIVO Institute for Jewish Research.

Every speaker, scholar and source at Sunday’s conference, Sunshine said, thinks a little differently and interprets their anarchism uniquely — like adherents of any other political theory or philosophy. But at its core, Yiddish anarchist history provides a counternarrative.

The all-day conference is broken into three themed panels: foundations of Yiddish anarchism; Russian revolutions and Yiddish anarchism; and language, identity, and culture.

For a Jewish American in 2019, a counternarrative to the previous century could be captivating.

“Zionism doesn’t have the allure that it once had for older generations,” said Sunshine. “Younger Jews are looking for ways to conceptualize a Jewish identity.”

He wasn’t talking about PhD student Diana Clarke specifically, though the candidate fits the bill.

“Yiddish is very sexy to young leftists,” Clarke told The Times of Israel. “That said, plenty of people in the world are not young leftists.”

On January 20, Clarke will be onstage in Manhattan, covering the role that post-vernacular Yiddish — that is, Yiddish not used in everyday life — plays in anarchism today. Clarke’s lecture is one of 10 on the program at Sunday’s Yiddish anarchism conference.

Clarke is pursuing a PhD at the University of Pittsburgh, studying the intersection of American Ashkenazi Jews and whiteness. The scholar also manages In Geveb, a Yiddish scholarly journal, while working on translating Yiddish poetry and writing a book.

Clarke’s path to Yiddish scholarship supports the narrative of a reconnection to Jewish heritage through 19th century Jewish anarchy. At Columbia, where Clarke earned an undergraduate degree, campus protests frequently pitted Students for Justice in Palestine against the Hillel Center as a result of Israel’s continued presence in the West Bank. During these demonstrations, coupled with the very visible Harlem gentrification surrounding and sometimes spurred by Columbia University itself, Clarke was reminded of sour memories of a Jewish upbringing in Massachusetts.

“As an Ashkenazi Jew growing up more or less in a conservative environment in the late ’90s,” Clarke recalled, “I was told Israel should matter a lot to me… Going to Israel was something for people whose families had money. Mine did not.”

Clarke was searching for something. Walking New York City’s streets — just as Clarke’s father always said was the best way to get to know a community — during four years of undergraduate study, Clarke came across the city’s Yiddish history.

“All of that experientially came together as I learned the history of the city among Yiddish speakers. I was so excited to find in my own history people living the life I wanted to live,” Clarke said, adding how those years of wandering resulted in an epiphany: “These are my people.”

New scholarship on a forgotten tradition

An introduction to what he calls the “lost world of Yiddish anarchism” was set to be delivered by co-organizer and Yiddish historian and scholar Kenyon Zimmer at the opening of the first panel.

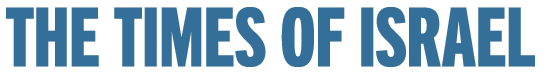

Buzhe,’ a young activist, poses along with her cohort of anarchists in Warsaw for this studio portrait taken around 1900. (Courtesy YIVO Institute for Jewish Research)

“Anarchism and anarchists really played an outsized role in the history of the Jewish labor movement and Jewish culture in the US and England,” Zimmer told The Times of Israel. “A lot of that has been forgotten or sort of lost piece by piece over time as scholars and others have written about the Jewish immigrant experience.”

Some of this history was lost in translation, said Zimmer, an associate professor of history at the University of Texas at Arlington. But there was arguably some intention in Yiddish anarchism’s centennial fade from mainstream knowledge.

“Anarchists get reduced to this brief, naive phase,” Zimmer explained, noting the more prevalent Jewish American story by which immigrants arrived, assimilated, experienced upward social and economic mobility, and steadily earned the American dream.

Anarchism doesn’t jive with the idea of “an irrepressible national Jewish identity,” he said. And of course there’s the force of Zionism, which summarily rejects anarchist tenets.

Asked why even to bother holding a conference about this Yiddish history if various agents so aptly erased it, Zimmer had a retort at the ready.

“[Yiddish anarchists] stand as an example of a substantial number of Jews in the Diaspora who rejected both assimilation into the cultural and political norms of their host, and rejected Jewish nationalism, whether by Zionism or another form,” Zimmer said. “It may resonate with certain currents of Jewish politics today that tend to question the actions of the State of Israel or the project being problematic as a whole.”

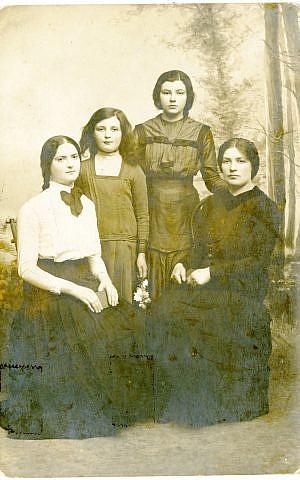

An advertisement for a Yom Kippur dance and buffet from anarchist periodical Di varhayt (The Truth), New York, September, 1889. (Courtesy YIVO)

An advertisement for a Yom Kippur dance and buffet from anarchist periodical Di varhayt (The Truth), New York, September, 1889. (Courtesy YIVO)

Jewish anarchism: Remember the anarchists

Conference host YIVO has been around since 1925 and miraculously survived the Holocaust.

“Most of its staff got killed,” director of public programs Alex Weiser told The Times of Israel. “It moved from Poland to New York City,” he said, recalling a smuggling operation that allowed it to be one of the only organizations to escape the Holocaust.

About 40 people staff YIVO today, mainly in New York. The organization also has an office in London and partnerships in Chicago and Buenos Aires. And it’s really very important, argued Weiser.

“Yiddish is the language of a history with which we have a discontinuity,” Weiser said. “Learning Yiddish can lead people to find alternatives to ‘being Jewish’ that aren’t prevalent in contemporary culture.”

YIVO aims to continuously enable global Yiddish learning, with, for example, a conference on Yiddish anarchism.

Social justice crusader Emma Goldman addresses a crowd in 1916, several years before her deportation to Russia by the United States government (public domain)

Social justice crusader Emma Goldman addresses a crowd in 1916, several years before her deportation to Russia by the United States government (public domain)

Many famous anarchists were linked to the Yiddish anarchist movement, such as Johann Most and Emma Goldman. Famous organizations include the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU) and the Yiddish anarchist newspaper the Fraye Arbeter Shtime (the Free Voice of Labor), “the largest and longest-lasting US anarchist publication,” according to YIVO.

“In the 1930s, the second generation of bilingual Jewish anarchists emerged, including Sam and Esther Dolgoff, and Audrey Goodfriend, whose influence is still felt in today’s anarchist movement,” the YIVO program description said.