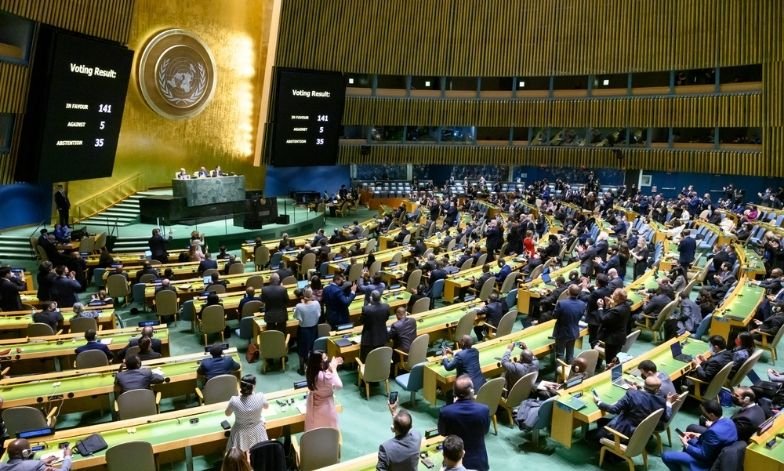

Zgromadzenie Ogólne ONZ. Źródło: Zdjęcie ONZ/Loey Felipe.

Zgromadzenie Ogólne ONZ. Źródło: Zdjęcie ONZ/Loey Felipe.

Czy uchodźcy żydowscy i arabscy są równi?

Czy uchodźcy żydowscy i arabscy są równi?

Lyn Julius

Tłumaczenie: Małgorzata Koraszewska

Mimo prawie miliona żydowskich uchodźców z krajów arabskich, Organizacja Narodów Zjednoczonych nadal ma obsesję wyłącznie na punkcie potomków uchodźców arabskich.

Co ciekawe, nie jest powszechnie wiadomo, że UNRWA faktycznie została powołana, aby pomagać uchodźcom po obu stronach konfliktu – zarówno arabskim, jak i żydowskim. Początkowo UNRWA definiowała osoby, za które była odpowiedzialna, jako „osobę potrzebującą, która w wyniku wojny w Palestynie straciła dom i środki do życia”.

Definicja ta obejmowała około 17 tysięcy Żydów, którzy mieszkali na obszarach ówczesnej Palestyny podbitych przez siły arabskie podczas wojny w 1948 r., oraz około 50 tysięcy Arabów mieszkających w granicach Izraela objętych zawieszeniem broni. Izrael wziął odpowiedzialność za tych ludzi i do 1950 r. usunięto ich z list UNRWA. To pozostawiło około 550 tysięcy Arabów palestyńskich – według szacunków New York Timesa z grudnia 1948 r. – pod opieką UNRWA.

W tamtym czasie nie istniała międzynarodowo uznana definicja tego, co stanowi uchodźcę. W 1951 r. Konwencja ONZ dotycząca uchodźców przyjęła następującą definicję:

osoba, która na skutek uzasadnionej obawy przed prześladowaniem z powodu swojej rasy, religii, narodowości, przynależności do określonej grupy społecznej lub z powodu przekonań politycznych przebywa poza granicami państwa, którego jest obywatelem, i nie może lub nie chce z powodu tych obaw korzystać z ochrony tego państwa, albo która nie ma żadnego obywatelstwa i znajdując się na skutek podobnych zdarzeń, poza państwem swojego dawnego stałego zamieszkania nie może lub nie chce z powodu tych obaw powrócić do tego państwa.

Definicja ta z pewnością odnosi się do 850 tysięcy żydowskich uchodźców, którzy uciekli przed prześladowaniami z krajów arabskich po 1948 roku i w większości przedostali się do Izraela. Powrót do tych krajów narażałby i nadal naraża ich życie.

Ciężar rehabilitacji i przesiedlenia 650 tysięcy uchodźców, którzy przybyli do Izraela, wzięli na siebie Agencja Żydowska i amerykańskie żydowskie organizacje humanitarne, takie jak American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee. Razem z ocalałymi z Holokaustu z Europy Wschodniej zostali przewiezieni do obozów przejściowych zwanych ma’abarot, gdzie warunki były bardzo złe.

W tamtym czasie amerykańska pomoc przeznaczona dla uchodźców z Bliskiego Wschodu miała zostać rozdzielona równo pomiędzy Izrael i państwa arabskie, a każda ze stron miała otrzymać po 50 milionów dolarów. Pieniądze na przyjęcie arabskich uchodźców przekazano UNRWA, zaś Stany Zjednoczone przekazały krajom arabskim kolejne 53 miliony dolarów na „współpracę techniczną”. W efekcie narody arabskie otrzymały podwójną kwotę pieniędzy przekazaną Izraelowi, mimo że Izrael przyjął więcej uchodźców, z których duża liczba została wypędzona z krajów arabskich.

W 1951 r. projekt ustawy przedstawiony Kongresowi był pierwszym i ostatnim przypadkiem, w którym stworzono jakikolwiek mechanizm zapewniający pomoc tym żydowskim uchodźcom. Całkowita kwota, jaką Kongres przyznał żydowskim i arabskim uchodźcom z Bliskiego Wschodu, odpowiadała dzisiejszej równowartości 1,5 miliarda dolarów.

Na wczesnym etapie konfliktu arabsko-izraelskiego ONZ została przejęta przez potężny blok wyborczy arabsko-muzułmański. Blok ten zaprojektował przejście od równego traktowania uchodźców do obsesji na punkcie tylko jednej grupy uchodźców – Palestyńczyków. Podczas gdy UNRWA opiekuje się wyłącznie uchodźcami palestyńskimi, wszystkimi pozostałymi uchodźcami na świecie zajmuje się Wysoki Komisarz ONZ ds. Uchodźców (UNHCR). W rzeczywistości istnieje 10 agencji ONZ zajmujących się wyłącznie uchodźcami palestyńskimi, z których większość nie jest uchodźcami, ale raczej potomkami uchodźców. Agencje te definiują status uchodźcy jako zależny jedynie od „dwuletniego pobytu” w „Palestynie” przed rokiem 1948. W definicji nie ma wzmianki o „strachu przed prześladowaniami” lub przesiedleniem.

Co najbardziej wymowne, spośród 65 milionów uznanych uchodźców na całym świecie, uchodźcy palestyńscy są jedynymi, którym pozwolono przekazywać swój status uchodźcy następnym pokoleniom. W rezultacie szacuje się, że obecna populacja palestyńskich „uchodźców” wynosi ponad pięć milionów, z czego tylko ułamek to uchodźcy zgodnie z jakąkolwiek rozsądną definicją.

Co więcej, jako jedyni wśród uchodźców na świecie uchodźcy palestyńscy mają przywilej żądania „repatriacji” zamiast przesiedlenia. Izrael z oczywistych powodów uważa to za rzecz niemożliwą do zaakceptowania.

Niemniej narody arabskie utrzymały te podwójne standardy zarówno jako broń przeciwko Izraelowi, jak i w celu uniknięcia znacznych kosztów osiedlenia samych uchodźców. W 1959 roku Liga Arabska przyjęła uchwałę nr 1457, która stanowiła, że z wyjątkiem Jordanii kraje arabskie nie przyznają obywatelstwa wnioskodawcom pochodzenia palestyńskiego. Ta dyskryminacja trwa do dziś.

W przeciwieństwie do miliardów dolarów, które społeczność międzynarodowa przeznaczyła na uchodźców palestyńskich, nie przeznaczono żadnej takiej pomocy dla uchodźców żydowskich. Wyjątkiem była dotacja w wysokości 30 tysięcy dolarów przyznana w 1957 r., której ONZ w obawie przed protestami ze strony swoich muzułmańskich członków nie chciała upubliczniać. Dotacja została ostatecznie zamieniona na pożyczkę, którą spłacił American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee.

Tylko dwukrotnie ONZ przyznała, że Żydzi uciekający z kraju Bliskiego Wschodu lub Afryki Północnej byli rzeczywistymi uchodźcami. W 1957 roku Wysoki Komisarz ONZ ds. Uchodźców August Lindt oświadczył, że Żydzi w Egipcie, którzy „nie mogą lub nie chcą skorzystać z ochrony rządu swojego kraju”, podlegają jego kompetencjom. W lipcu 1967 r. UNHCR uznała Żydów uciekających z Libii za uchodźców objętych mandatem UNHCR.

Nie trzeba dodawać, że żaden z tych Żydów nie uważa się już za uchodźcę. Mimo przeżycia ogromnych trudności są teraz pełnoprawnymi obywatelami Izraela lub innych krajów.

Czy to zbyt wiele, jeśli prosimy o podobne humanitarne rozwiązanie trudnej sytuacji uchodźców palestyńskich?

Lyn Julius – Dziennikarka, współzałożycielka brytyjskiego stowarzyszenia HARIF, Żydów pochodzących z Północnej Afryki i krajów Bliskiego Wschodu; stowarzyszenia informującego o liczącej trzy tysiące lat historii Żydów na Bliskim Wschodzie i o losie tej mniejszości wyznaniowej i religijnej w XX wieku. Rodzina Lyn Julius pochodzi z Iraku.

Zawartość publikowanych artykułów i materiałów nie reprezentuje poglądów ani opinii Reunion’68,

ani też webmastera Blogu Reunion’68, chyba ze jest to wyraźnie zaznaczone.

Twoje uwagi, linki, własne artykuły lub wiadomości prześlij na adres:

webmaster@reunion68.com