For Glazer, as for Bell and other New York Intellectuals who came to be known as neoconservatives—not to be confused with the neoconservatives of the 2000s—the students’ anarchic desires for revolutionary change posed a threat to the fragile institutions of liberal democracy. Glazer remarked that in 1964, there was uncertainty as to whether the radicals threatened liberalism since their ends had merit and they were not communist-aligned. By 1969, citing “four and a half years of increasing escalation” and persistent threats to “free speech, free research and free teaching,” Glazer felt that his band of skeptics had been vindicated. He criticized the tepid response of liberals within the university to the antics of the radicals. Instead of standing up for bourgeois liberal democracy, they caved in to authoritarian demands to control the curriculum.

The challenge to free speech, liberal institutions, and reason affected Glazer and Bell deeply. But they also realized this was not just a question of liberty but of tradition: No one had thought about how to define and defend what the radicals were trying to overthrow. Instead of simply championing freedom and reason, the neoconservatives developed a countervailing appreciation of Western tradition and hierarchies of excellence.

What began as concern for the Western Enlightenment and classical inheritance expanded into an appreciation, for Bell, of Jewish tradition and religion more generally. This is not to say Bell was a believer. What he valued, in a Durkheimian sense, was the meaning that intragenerational solidarity and sense of continuity religious tradition provided. Thus he could criticize both detraditionalized Christian fundamentalism and secular hedonism. Bell came to formulate his position as a “socialist in economics, a liberal in politics, and a conservative in culture.” “Socialist” referred to Bell’s willingness to use evidence-based social policy to address problems of deprivation and inequality. This social democratic approach was married to political liberalism—hostility to communist authoritarianism and anarchist mob tyranny—and a cultural outlook which valued religious and ethnic tradition alongside intergenerational communities of meaning.

The neoconservatives were alarmed at what they saw as the counterculture’s colonization of the American upper middle class. “Violence is extolled in the New York Review of Books, which began with only literary ambitions,” wrote Glazer. “Tom Hayden, who urges his audiences to kill policemen, is treated as a hero by Esquire; Eldridge Cleaver merits an adulatory Playboy interview.” Meanwhile, the older elite conservatism of National Review had little to say, having become deeply unfashionable and moribund.

Bell located the sources of the “adversary culture” in the antinomian modernism that began in the arts in the late 19th century. Modernism, for Bell, was a cultural sensibility, a repudiation of tradition. In the early 20th century, Christian, classical, and national motifs were replaced by the shock of the new: abstraction, surrealism, and Dada. This outlook was typically the preserve of small groups of bohemian intellectuals like the Greenwich Village “Young Intellectuals” of 1912-17 or early New York Intellectuals, who championed modern art against the neotraditionalism of American Scene Regionalists like Thomas Hart Benton. This “lyrical left” tended to deride bourgeois morality and ethnic majority traditions as stifling and uninteresting. In 1916, Randolph Bourne dubbed his own ethnic group—Anglo-Protestant Americans—narrow and provincial, urging them to embrace cosmopolitanism. In the 1920s, H.L. Mencken referred to Anglo-Americans as second-rate, unexpressive ignoramuses whose religion resembled voodoo. #Cancelwhitepeople was born from these Protestant anti-WASP loins.

Bell saw that the fight against fascism had discredited the right in Europe and America. Conservative intellectuals like the Southern Agrarians or Ezra Pound fell out of favor while intellectual life in the 1950s came to consist of an internecine struggle between the Marxist left and the modernist left. After McCarthyism, it was the latter that emerged the winner and rode a wave of structural change to victory.

In the 1960s, the GI Bill paid many ex-servicemen to attend college The share of 18- to 24-year-olds at university jumped from 15% in 1950 to 33% in 1970, as university sinecures opened up for many formerly impecunious bohemians. Meanwhile television, which only reached 9% of American households in 1950, spread to 93% by 1965, allowing for the swift diffusion of the modernist sensibility from nodes in Washington, New York, and Hollywood. As Bell remarked in the Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism (1976), “The life-style once practiced by a small cénacle … is now copied by many … [and] this change of scale gave the culture of the 1960s its special surge, coupled with the fact that a bohemian lifestyle once limited to a tiny elite is now acted out on the giant screen of the mass media.”

The culture-quake of the 1960s was less a qualitative change of ideas than a quantitative takeoff in the reach of the adversary culture. The decade was not entirely bereft of ideological innovation though: The cross-fertilization of the Frankfurt School’s Marxist cultural criticism with new Third Worldist and black liberationist currents transposed the Marxist framework from class to identity. This new identity politics left merged with the older bohemian left to produce what I term “left-modernism”—the dominant ideology of our time. Shorn of overt Marxism, it served as the cultural sensibility of the rising knowledge class in large corporations, media, and government that the neoconservatives dubbed the New Class.

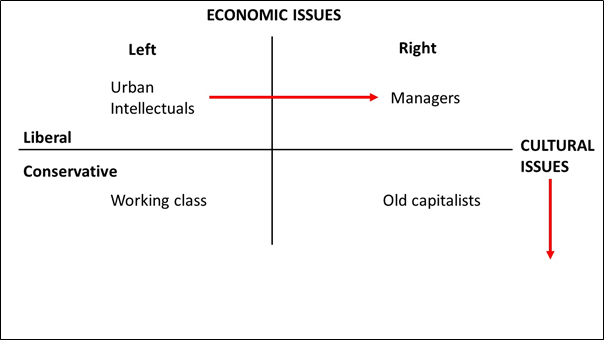

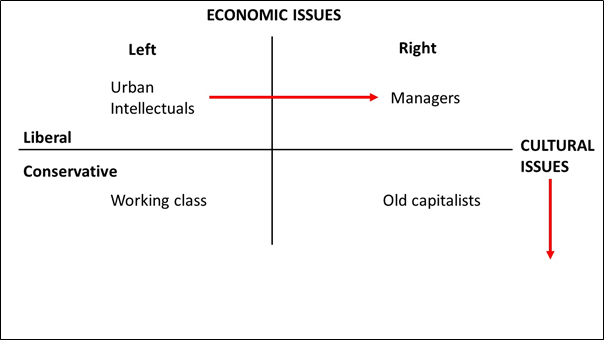

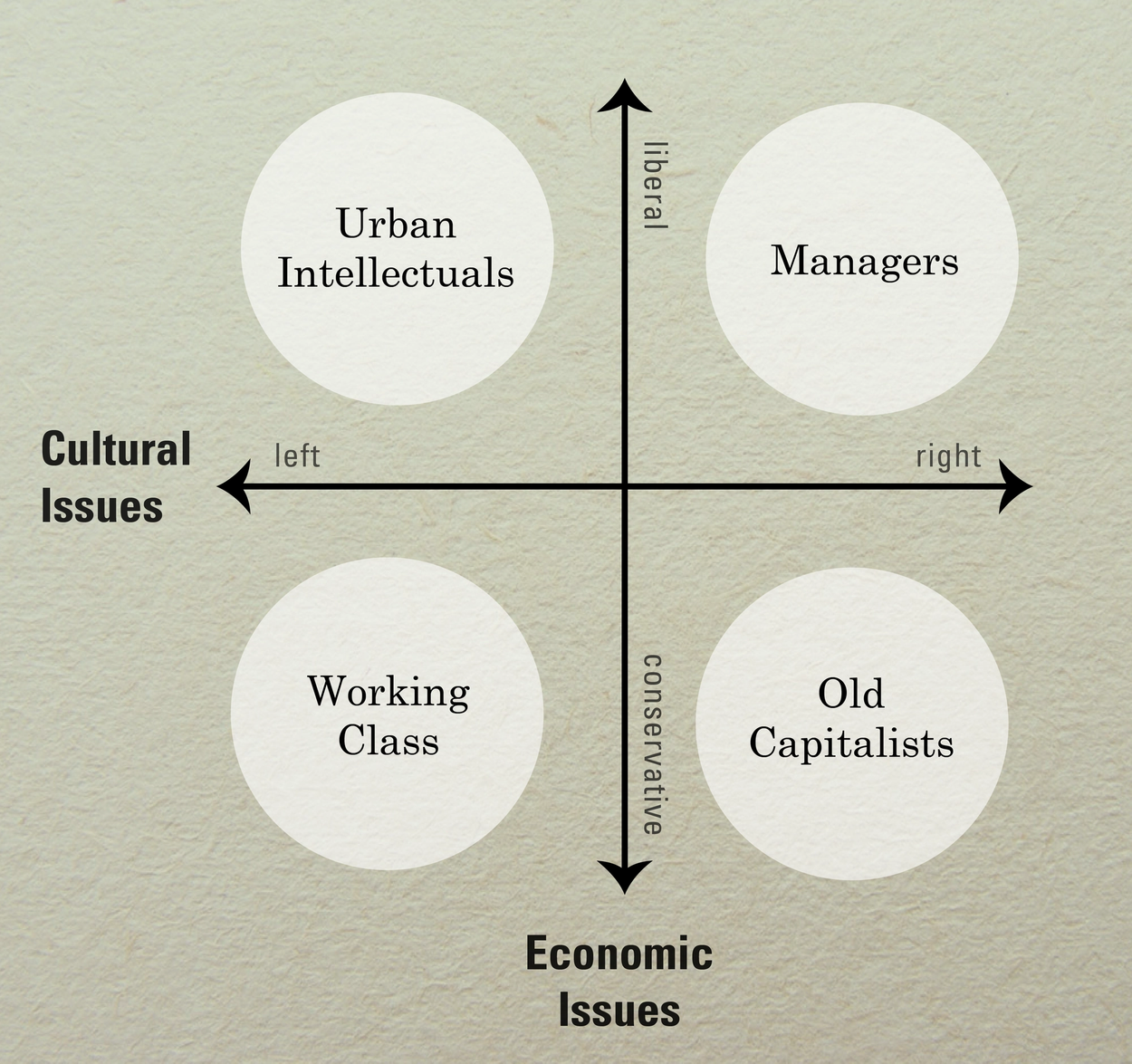

As early as 1965, New York Intellectual Lionel Trilling had marveled at the way the adversary culture “captivated” the middle class. In 1979, Bell produced the diagram in figure 1, showing how a new liberal-conservative cultural line bisected the old left-right economic divide. Where once the workers and urban intellectuals shared a common leftist cause against the free market managers and “old capitalist” small businessmen, things were now changing. Modernist intellectuals transmitted their adversary culture to the knowledge class of managers—as shown by the horizontal arrow—drawing these two groups closer together while alienating the traditional working class, who now found themselves having more in common with small businesspeople. Meanwhile, rising education and the growth of the tertiary sector in major metro areas reduced the clout of traditional America, as shown by the down arrow indicating an expansion of the liberal demographic.

Figure 1DANIEL BELL, ‘THE WINDING

Since the 1980s, Alan Abramowitz shows that conservative voters have increasingly voted Republican while liberals align with the Democrats. Suburban whites with degrees are moving Democratic while noncollege whites, often from exurban or rural areas, vote for Donald Trump. In Britain, there is currently no class difference between left and right parties, but a massive, Brexit-driven divide in cultural outlook rooted in immigration attitudes. Attitudes to race, gender, and sexuality now underpin the partisan hatreds that are intensifying polarization in America and fueling populism in western Europe.

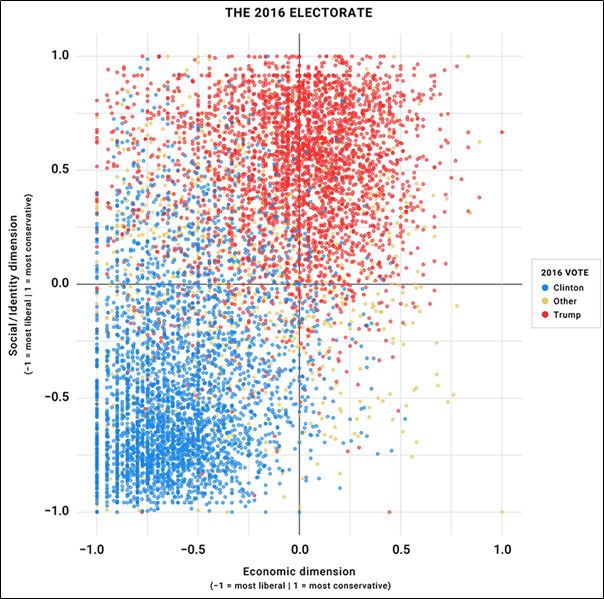

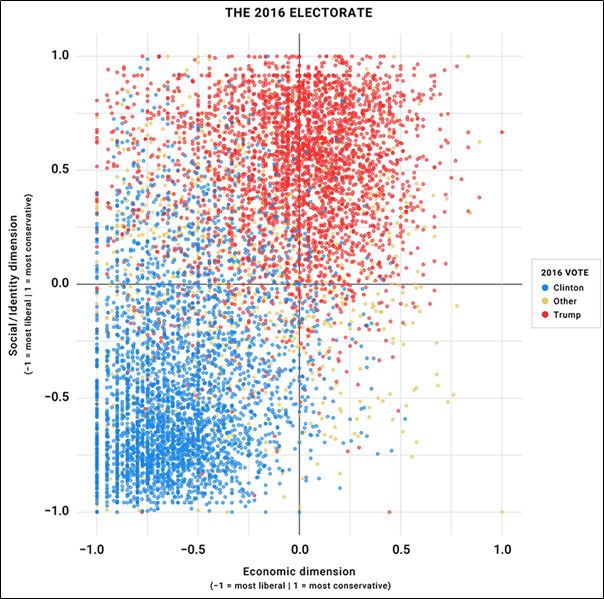

Figure 2LEE DRUTMAN, ‘POLITICAL DIVISIONS IN 2016 AND BEYOND,’ VOTER STUDY GROUP, JUNE 2017

Figure 2LEE DRUTMAN, ‘POLITICAL DIVISIONS IN 2016 AND BEYOND,’ VOTER STUDY GROUP, JUNE 2017

This new terrain renders the pro-market “country club” think tank establishment increasingly irrelevant. For, as figure 2 shows, few of Trump’s voters are liberal on both cultural and economic questions. They’re conservative on culture, clustering toward the top, but are centrist on economics, with most in the top-middle rather than top-right quadrant. Democrats are more clustered in the bottom-left quadrant, where they are left on both economics and culture.

The adversary culture poses two broad threats to the communal solidarity that left-conservatives hold dear. First, it erodes the bonds of family and religious morality, or what Harvard political scientist Robert Putnam calls “bonding social capital”—the bonds within communities. Second, the radical egalitarianism and expressive individualism of the adversary culture eviscerates collective tradition, memory and nationhood, thus undercutting what Putnam calls “bridging social capital”—the bonds uniting communities into a commonweal. Bonding problems are evident in the rising rate of white working-class illegitimacy and opioid addiction documented in Charles Murray’s Coming Apart. These issues engage religious and pro-family conservatives. Bridging problems bulk larger for national conservatives, who decry the influence of mass immigration, multiculturalism and attempts to deconstruct national histories and demonize white majorities.

Bell’s critique of hedonism laments its impact on bonding capital. In the 1970s and ’80s, Bell was accompanied by writers in the Protestant Populist-Progressive tradition like James Lincoln Collier and Wilson Carey McWilliams, as well as by Christopher Lasch and his coruscating attacks on American’s narcissistic individualism. These Protestant writers lionized the American Victorian-Protestant tradition of family, religion, and restraint over expressive individualism. They also rejected consumerism and economic inequality, embodying the same left-conservative mix as their Populist-Progressive forbears.

While their religious conservatism proved influential in the Republican Party from the 1980s, the leftist elements of their thought were jettisoned in favor of tax cuts and monetarism. Kevin Phillips is an important figure here. A middle-class New York WASP, he admired the New Deal and identified with “Idaho loggers, Carolina farmers, and ethnic steelworkers” against elite Northeastern liberals. He initially poured his energies into organizing the religious right, but, as John Judis notes, was repelled by its fundamentalism and pro-market creed. Phillips’ sense of tradition was as much national as religious, decrying elite detachment from the working class. Likewise, in his last book, The Revolt of the Elites (1994), Lasch castigated America’s elites for their post-national detachment from popular national identity, a theme echoed in Samuel Huntington’s final book, Who Are We (2004).

The American mainstream right chose to prioritize religious conservatism between the ’80s and 2000s, in part because talk of immigration and nationhood would challenge the modernist left’s most sacred value of race and would therefore be painted as racist. Very few left-conservative writers were willing to directly address bridging capital problems, especially if this involved questioning the rapid immigration and associated ethnic changes associated with amnesties, lax border enforcement, and bipartisan support for low-cost immigrant labor. In 1992 and 1996, Pat Buchanan’s Republican primary bid revealed the potency of these neglected issues.

At this time, Michael Lind and John Judis addressed questions of social cohesion from a left-conservative standpoint. Both blended influences from the Jewish neoconservative circles in which they operated with the Protestant Populist traditions they cherished. Lind’s landmark Next American Nation (1995) decried the effects of mass immigration on the American worker’s income and national attachments. In a hard-hitting piece, “For a New Nationalism,” in the New Republic that year, Lind and Judis rejected “the conception of the United States as a multinational democracy, epitomized by the multiculturalist movement.” They opposed affirmative action, endorsing the idea of the United States as “a nation-state with a common culture.” For them, “the backlash against escalating levels of Third World immigration reflects not just racism but genuine concerns about the displacement of the native-born working poor.” While others, such as Francis Fukuyama or Arthur Schlesinger, were willing to criticize multiculturalism, Judis and Lind’s critique of immigration and embrace of state redistribution set them apart.

This new atmosphere rendered Nathan Glazer’s concerns more relevant than Bell’s. Indeed, Bell related to me a few years before his death that he didn’t relate to “national identity” but rather to his ethnic tradition. Glazer’s conservatism had always been more national than Bell’s. Though mindful of the immigrant experience and nativism, he was concerned with the fraying of the country’s bridging social capital. With regard to immigration, he wrote in 1995 that: “I think one of the great yearnings of Americans today is for more stability. One thing that immigration inevitably brings is a lack of stability.”

Long a critic of affirmative action and multiculturalism, in 1998, Glazer wrote in the National Interest that the epic of westward European settlement and freedom that defined the country had been challenged. While sympathetic to the need to include those who felt excluded from this national tradition, he remarked that the national epic had become fragmented and doubted whether the “improving of group relations can replace the conquest of a continent as a subject of an epic.” Glazer examined my doctoral dissertation at the London School of Economics (LSE) that year, relating that he thought American national identity had historically always blended civic and ethnic elements.

Up to that point, I had not realized that Glazer and my supervisor, Anthony D. Smith, knew each other. This was also brought home to me by a note from Glazer to Smith in a copy of Glazer’s Affirmative Discrimination (1975) in Smith’s office. Smith, whom I first encountered by accident during my time at LSE, was an apolitical scholar, but his work is a vital piece in the story of national conservatism. As an observant English Jew, Smith had a very different view of Zionism and Jewish tradition than his co-ethnics: LSE supervisor Ernest Gellner or neo-Marxist historian of nationalism Eric Hobsbawm. Where Gellner and Hobsbawm viewed nations as the functional or instrumental inventions of state elites, Smith took the deeply unfashionable position, also taken by Orwell, that they represented cultural traditions which were reproduced by romantic intellectuals and the mass public, who were emotionally attached to them. Artificial nations like many postcolonial states or Yugoslavia, as with modern technocratic constructs like the European Union, did not succeed because they failed to “resonate” with existing popular myths and symbols.

Smith defended the cultural value of national traditions, and his work influenced fellow academic Steven Grosby, who was a regular at LSE conferences on nationalism, engaging in a heated exchange with Hobsbawm on one memorable occasion. Grosby in turn influenced Yoram Hazony, the godfather of national conservatism and author of The Virtue of Nationalism, and Rich Lowry of National Review, whose The Case for Nationalism also draws on Smith’s insights.

Why is left-conservatism rising now? First, there is the exhaustion of neoconservatism, as distinct from the small-n neoconservatism of Glazer and Bell. The neocons propounded a right-wing form of liberal universalism that sought to make peace with the modernist left by pursuing issues that avoided confronting the left’s sacrilization of race. It sounded a pro-immigration note, and soft-pedaled resistance to affirmative action and multicultural education in favor of tax cuts and a muscular foreign policy. But the Cold War ended in 1989 while the bloody Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts ran into the sand, consuming ideological capital.

Meanwhile the 2007-08 financial crisis and rising inequality shook people’s faith in the doctrine of free market globalization. On the left, degree-holding metropolitan liberals became more dominant in the Democratic Party, and cast aspersions on white working-class traditions. All the while, what Thomas Piketty calls the “Brahmin Left” captured and staffed unions and left-wing parties as their mass memberships dwindled. This allowed them to complete the “cultural turn” away from class towards race, gender, and sexual identity politics. In the process, many blue-collar whites fell away.

Soon after, in Europe, there was a significant increase in immigration and unprecedented levels of foreign-born population. This produced a populist upsurge which began with the 2014 European Union elections, continued through the rise of populist right parties in Western Europe in 2015, and culminated in Brexit. Trump’s victory in 2016 was followed, in 2019, by the rise of the anti-immigration Salvini in Italy and Vox in Spain.

recomended by: Leon Rozenbaum

The populist moment, coming after the exhaustion of neoconservatism, upended the world of ideas on the right. Theresa May in Britain, Mark Rutte in the Netherlands, Sebastian Kurz in Austria, and even Emmanuel Macron in France sought to stanch losses to populist parties by adopting tougher positions on immigration and integration. In the United States, Trump’s success influenced Marco Rubio and Josh Hawley, who now speak the language of economic protectionism rather than tax cuts.

Left-conservatism foregrounds nationalism more than religion. Where the religious right was evangelical and universalist, thus dovetailing nicely with neoconservatism’s missionary liberalism, national conservatism is traditionalist, particularist, and isolationist. National conservatives endorse left-wing policies such as protectionism, infrastructure spending, and support for welfare programs like Social Security alongside conservative ideas such as immigration restriction and nationalism. In Europe, the mix is similar, albeit with a stronger focus on taxing the rich.

In the mid-2010s, British “post-liberalism” has come to coalesce around the online magazine Unherd. One of its leading avatars is David Goodhart, who founded the center-left periodical Prospect in 1995. Influenced by Lind, Goodhart wrote a controversial article in Prospect in 2004 titled “Is Britain Too Diverse” arguing that diversity and solidarity existing in tension, and that high levels of the former were incompatible with the desire to protect the welfare state. His Road to Somewhere (2017) juxtaposed socially mobile “Anywheres” who attach primarily to credentials rather than the nation with rooted “Somewheres” who lack degrees, live near their place of birth and cherish national traditions. The new Social Democratic Party (SDP) of William Clouston, fireman-intellectual Paul Embery, and the patriotic Blue Labour wing of the Labour Party share similar beliefs and positioning.

Perhaps the essence of left-conservatism is its plea for social cohesion and a concomitant rejection of post-national elites with their one-two punch of economic liberalism and the adversary culture. At root, the New Class/Anywhere elite is attached to a transnational status culture, much like Europe’s aristocracy prior to the age of nations. Michael Lind captures this milieu well in The New Class War (2020), contrasting those who “derive their personal status from their prestigious occupations, not their local or national communities; abandon their low-status class or ethnic or regional accents in order to succeed in metropolitan careers; and jettison ancestral traditions in favor of ever-changing transnational elite fashions.” After decades in the wilderness under both left- and right-wing governments in the West, left-conservatives are attaining new levels of political power and cultural visibility in the face of a new radicalism that eerily recalls the 1960s.

Eric Kaufmann is Professor of Politics at Birkbeck, University of London. His latest book is Whiteshift: Populism, Immigration and the Future of White Majorities.

Czymże jest nazwa? Pochodzenie Judei, Filistii, Palestyny i Izraela

Czymże jest nazwa? Pochodzenie Judei, Filistii, Palestyny i Izraela

Starożytne królestwa Izrael, Judea i Filistia

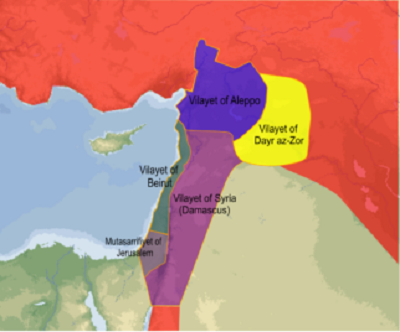

Starożytne królestwa Izrael, Judea i Filistia Prowincja osmańskiej Syrii

Prowincja osmańskiej Syrii Dynastia Hasmoneuszy (Machabeuszy)

Dynastia Hasmoneuszy (Machabeuszy) Brytyjska Palestyna Mandatowa

Brytyjska Palestyna Mandatowa

A blend of left-wing policies—like support for Social Security and infrastructure spending—with favored conservative ideas, like nationalism and immigration reform, is finding its voice

A blend of left-wing policies—like support for Social Security and infrastructure spending—with favored conservative ideas, like nationalism and immigration reform, is finding its voice