The Lost Synagogue of Aleppo

The Lost Synagogue of Aleppo

MATTI FRIEDMAN

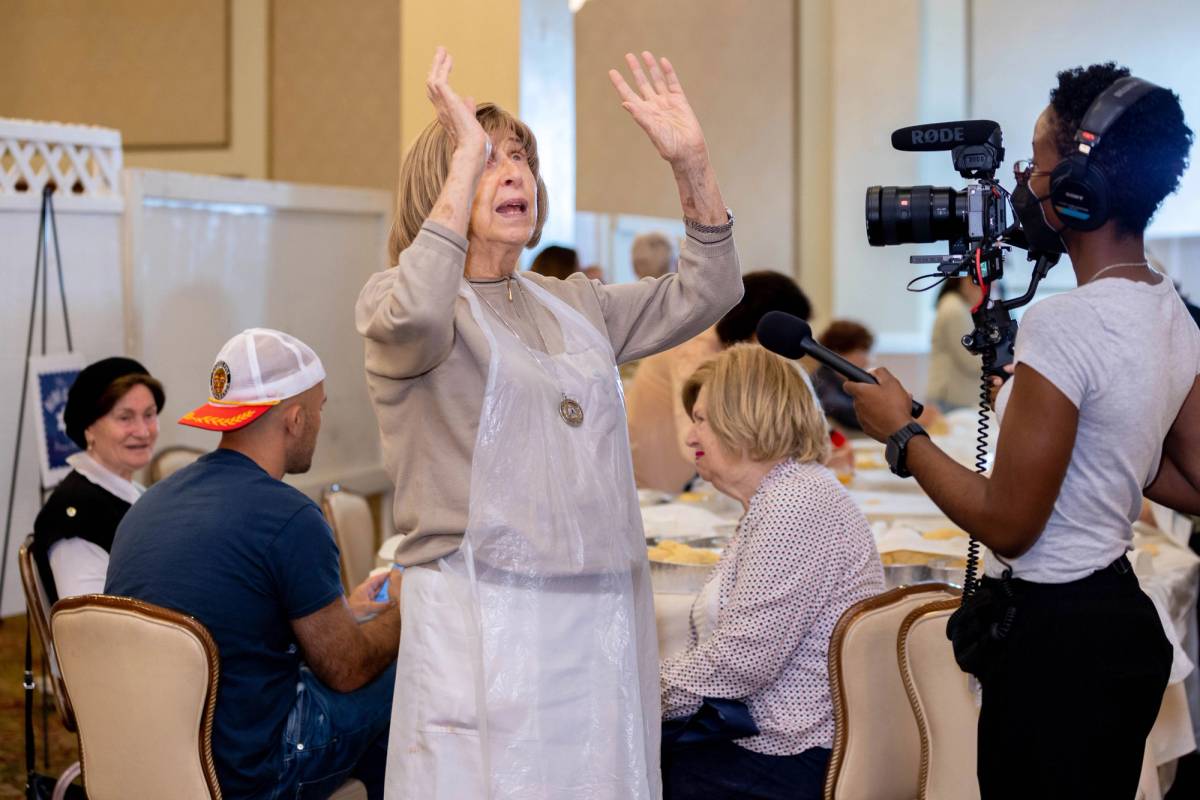

Visitors at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem experience the Great Synagogue of Aleppo in virtual realityZOHAR SHEMESH

Visitors at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem experience the Great Synagogue of Aleppo in virtual realityZOHAR SHEMESH

.

A new virtual reality exhibit at the Israel Museum brings to life the Great Synagogue, and the great collapse of multinational Jewish life.

.

One day in 2016 the end came, again, for the Great Synagogue of Aleppo. Fighting between the Assad government and rebels had ripped the ancient city apart and hundreds of thousands of people were already dead across Syria, so it doesn’t seem right to dwell on the loss of a building—but this was, perhaps, the greatest building in the Jewish world. Prayers began at the site, scholars believe, around the fifth century CE, maybe earlier, and continued until the 1990s, when the last Jews left the city. There were breaks only for events like the Mongol invasion that leveled much of Aleppo in the 13th century, for the occasional devastating earthquake, and for the Arab riots and arson that accompanied the United Nations vote on Israel’s creation in 1947. No other synagogue on earth embodied 15 continuous centuries of Jewish life and memory.

Since the community’s final departure, the building had been empty but intact, guarded by the regime, upkeep covered discreetly by members of the Aleppo Jewish diaspora. But photos after the 2016 fighting showed pulverized stonework, a courtyard full of rubble, twisted iron railings, and Hebrew engravings blasted off the walls. The Great Synagogue was gone.

And yet last week I walked past the high bimah, 20 steps off the ground, illuminated by Syrian sunlight pouring through the colonnades. I saw a leaky pump in the courtyard surrounded by gleaming puddles, and took in the paint peeling on the columns and the deep medieval windows. There was no damage. It was all so vivid I put out a hand to touch a wall, forgetting that it wasn’t real. I paused by the famous “sealed ark,” one of the synagogue’s seven repositories for Torah scrolls, which was sealed at a time and for a reason that no one remembers. The ark was home, according to local legend, to a magical snake that appeared on occasion to save the community from its enemies. I read the plaque honoring a donor named Eli Bar Natan, inscribed sometime before the ninth century. I peeked into the Cave of Elijah, a nook that housed the Aleppo Codex, the most perfect copy of the Hebrew Bible, for 600 years.

It was while writing a book about the codex that I heard many hours of recollections of the Great Synagogue from elderly Aleppo Jews, and spent many more hours imagining the place. Many of the memories had nothing to do with ritual: One elderly woman remembered the eerie whispering sounds she heard in the building’s corners as a little girl, and one spot where you could stand to feel a strange breath of air. The synagogue had seen so many human generations, had heard the name of God pronounced and the story of creation repeated so many times that at some point it seemed to have come alive itself.

I crossed from the old part of the building used by the original Arabic-speaking community, the musta’arabin, into the brighter “new” wing built for refugees from Spain after the expulsion of 1492—and then the simulation crashed. A Windows screen popped up and an apologetic technician took my headset; the exhibit wasn’t open to the public yet, and there were still a few glitches in the software. It took a few moments to remember where I was, and that the synagogue was still gone.

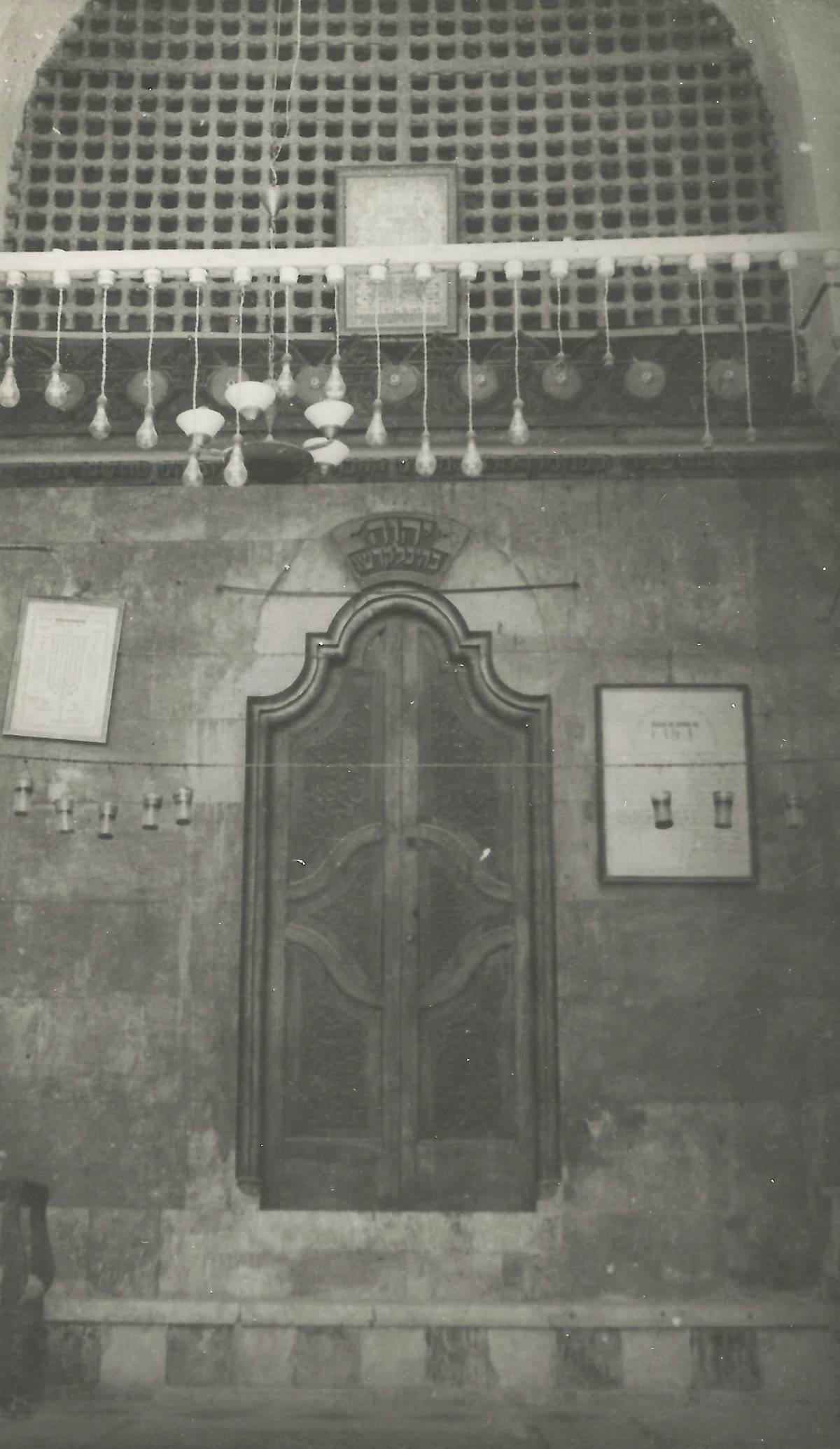

This gallery at the Israel Museum, the one called Jewish Art and Life, has several recreated synagogues, like the beautiful one from Vittorio Veneto circa 1700, and one from Suriname with a remarkable sand floor. But the new exhibit, which opened this month, marks the first time the museum has used virtual reality. The “exhibit” is little more than four chairs and four headsets. The curators, who hail from an earlier generation, seem a bit defensive about the technology, aware that it might be deemed frivolous. They make sure to explain that this simulation isn’t a fictional recreation, but is based entirely on a remarkable series of 51 photographs shot in November 1947 by an Armenian photographer working for a Jewish woman, Sarah Shammah, whose family preserved the historical treasure in their Jerusalem home. This is not, in other words, hi-tech entertainment, but a display of photographic documentation using new means. “Sarah’s photos are the original artifacts,” said Rachel Zarfaty, one of the curators. “All we did was change the platform.”

Photos taken in November 1947 by an Armenian photographer working for Sarah Shammah, whose family preserved the images in their Jerusalem homeCOURTESY ORA AND AVRAHAM HAVER

Photos taken in November 1947 by an Armenian photographer working for Sarah Shammah, whose family preserved the images in their Jerusalem homeCOURTESY ORA AND AVRAHAM HAVER

One day that month in 1947, just weeks before the outbreak of Israel’s Independence War, Shammah had the ancient building recorded in its entirety by the photographer, whose name has been lost. She seems to have had a premonition. Only days later, on Nov. 29, the United Nations voted to partition the British Mandate territory of Palestine into Arab and Jewish states, upon which a mob in Aleppo rioted and torched Jewish homes, shops, and synagogues, including much of the Great Synagogue. Similar riots in other cities spelled the end for Jewish life in Arab countries. Most of Aleppo’s Jews escaped immediately afterwards, though a remnant limped on for a few more decades under the boot of Syria’s military dictatorship, praying in part of the building. After the 1947 riot, Shammah made it to Jerusalem via Beirut with the negatives. The borders were cut a few months later, and she never saw her city again.

The idea of a virtual-reality resurrection of the synagogue originated not with the museum but with a group of four creative partners, two in Israel and two in Berlin, with backgrounds in film, history, and tech. One of them is Avi Dabach, 50, an Israeli director whose great-grandfather Ezra Dabach was the sexton of the Great Synagogue. Avi’s grandfather grew up in an adjacent apartment and used to tell him stories about the building: “He’d say, I can’t describe how beautiful it is, and when Israel and Syria make peace I’ll take you there on the first plane,” he remembered. The first plane has yet to take off, but five years ago, Shammah’s son Avraham, now 89, showed Avi his mother’s photographs. The partners spent years turning them into a virtual reality simulation. When you put on the headset at the Israel Museum, you’re visiting the synagogue on a specific day in November 1947, the last moment that the community was whole. One scenario allows you to take a tour with a ghostly simulation of Asher Baghdadi, the sexton who took over from Avi’s great-grandfather in 1928. A second scenario is a dramatization of the events around Shammah’s visit to the synagogue as the Middle East imploded around her.

Sarah ShammahCOURTESY ORA AND AVRAHAM HAVER

The precise details of what happened to the real building remain unclear, but it happened as Assad’s army fought to regain control of Aleppo from rebel forces in 2016. The slightly younger Jobar Synagogue in Damascus had already been destroyed two years earlier. There’s a blurry photo showing armed fighters in the Aleppo synagogue, and then there are other photos that show walls riddled with bullet holes and others reduced to rubble. Two years later, two 360-degree images on Google Street View (here and here) show signs of a cleanup, but the building’s a shell.

The recreated synagogues of the Israel Museum, including this one, are beautiful and memorable and deeply sad. The curatorial energy and creativity can’t obscure what all of this tells us, which is that the Jewish world is contracting. The fact is that in the lifetime of our parents and grandparents, Jews were eradicated in much of the Christian world and erased from the world of Islam. It’s not just the Great Synagogue of Aleppo—it’s the houses of worship in Tataouine or Oran, the synagogues of Galicia and Romania, the ones in grand Italian towns and obscure Polish hamlets. And what about Cochin, or Kaifeng, or, for that matter, Knoxville, the Carolinas, and the Caribbean? Much of the tenuous, beautiful, and strange variety of Jewish life that existed a century ago is gone. The vast majority of what remains plays out in the state of Israel and a few big cities in North America.

The new simulation had the effect of bringing the Aleppo synagogue to life for a moment. The impression of being in that building, even if it was only virtual, was so potent for me that it still hasn’t quite worn off. Everyone who can visit the simulation at the Israel Museum should go. But tech has a way of showing us something and leaving us hollow. When the headset came off, I was left with the same feeling I’ve had when reconnecting online with a friend from the past—the knowledge of what existed not long ago, and how truly gone it is.

Matti Friedman is a Tablet columnist and the author, most recently, of Who by Fire: Leonard Cohen in the Sinai.

Zawartość publikowanych artykułów i materiałów nie reprezentuje poglądów ani opinii Reunion’68,

ani też webmastera Blogu Reunion’68, chyba ze jest to wyraźnie zaznaczone.

Twoje uwagi, linki, własne artykuły lub wiadomości prześlij na adres:

webmaster@reunion68.com

%20(49).jpg)

%20(13).jpg)

%20(24).jpg)

%20(36).jpg)

%20(22).jpg)

%20(43).jpg)

%20(44).jpg)

%20(35).jpg)

%20(50).jpg)

%20(52).jpg)

%20(55).jpg)

%20(57).jpg)

![MKiDN_kolor_od_11.2021.png [64.32 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2021/11/30/4f9c59b58e2fbf630436ae51e82faaad/png/jhi/preview/MKiDN_kolor_od_11.2021.png)