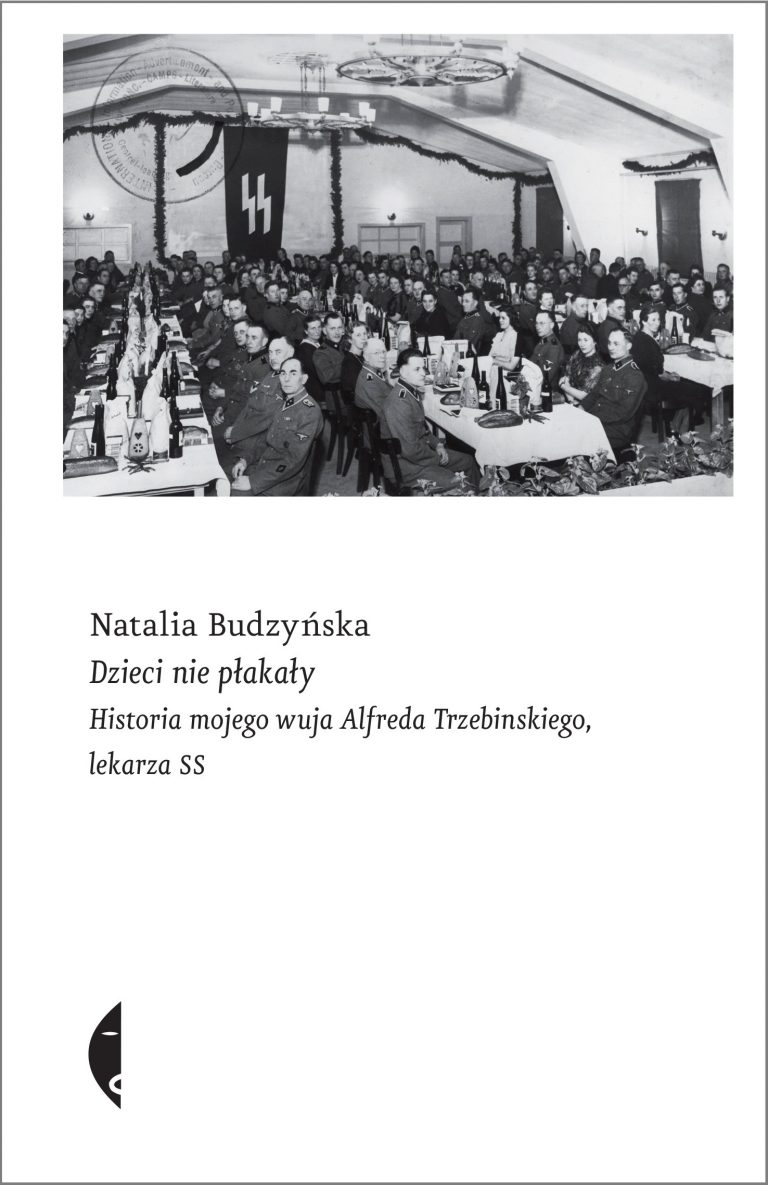

Mój wujek zbrodniarz. Recenzja reportażu „Dzieci nie płakały” Natalii Budzyńskiej

Mój wujek zbrodniarz. Recenzja reportażu „Dzieci nie płakały” Natalii Budzyńskiej

Lech M. Nijakowski

Częściej zdarza nam się czytać książki potomków ofiar niż oprawców. Reportaż Natalii Budzyńskiej należy do tych ostatnich. To nakreślony bez retuszy portret wuja Alfreda Trzebinskiego, lekarza SS skazanego za zamordowanie dzieci w obozie koncentracyjnym. W jego biografii przegląda się wielka historia o najbardziej szpetnym obliczu.

„Dziadek z Wehrmachtu” wszedł już do języka polskiego jako fraza oznaczająca rodzinne tajemnice, jakoby kompromitujące aktywnych w sferze publicznej wnuków. Ale II wojna światowa pozostawiła w spadku także gorsze rodzinne karty – zbrodniarzy-krewniaków i skoligaconych oprawców. Mało kto w „narodzie ofiar” ma odwagę mierzyć się z tą przeszłością. Nie pasuje ona do heroicznych narracji, pozwalających stawiać się w długiej linii odważnych patriotów. Już z tego punktu widzenia książka Natalii Budzyńskiej zasługuje na uznanie, gdyż opisuje biografię wuja z SS.

A ściślej mówiąc: Alfred był synem Stefana, brata pradziadka autorki. Pokrewieństwo nie jest zatem aż tak bliskie, jak sugeruje tytuł, ale nazistowski zbrodniarz konsekwentnie nazywany jest w książce „wujem”. Pochodził on z arystokratycznej wielkopolskiej rodziny Trzebińskich (dlatego zapewne zachował nazwisko, choć bez „kompromitującego” polskiego ogonka), legitymującej się herbem Szeliga, co utwierdzało go w przekonaniu o własnej wyjątkowości. Za młodu wybrał niemieckość, jak część jego krewniaków, a potem utożsamił się z ruchem narodowosocjalistycznym, ukrywając swoje związki z polskością.

W książce poznajemy nie tylko zrekonstruowaną biografię Alfreda, lecz także stopniowe odkrywanie rodzinnej tajemnicy przez autorkę. Opisuje ona wydarzenia i przeczucia, które po latach interpretuje jako oznaki trupa w szafie. W opisie tym brak sentymentalizmu i tanich literackich chwytów. Budzyńska nie cofa się też przed brutalną rodzinną wiwisekcją. Zastanawiając się, jakie relacje łączyły Alfreda z jej dziadkiem Jerzym, pisze: „Więc spotykali się: Alfred zapatrzony w wielkie Niemcy, Jerzy zapatrzony w wielką Polskę. Łączyło ich jedno: antysemityzm” [s. 33]. I dodaje: „Nie tylko to. Także fakt, że obaj nie doczekali starości oraz rodzaj nagłej, nienaturalnej, tragicznej śmierci: umarli przez powieszenie. Mój dziadek powiesił się sam, jego żona była w ciąży i dokładnie miesiąc później urodził się mój ojciec. Alfred został powieszony przez brytyjskiego kata, słynnego Pierrepointa, po ogłoszeniu wyroku w procesie załogi KL Neuengamme” [s. 34]. Przyglądając się studiom pradziadka nad genealogią rodziny, podejrzewa, że wynikały one z potrzeb jego bratanka, który musiał przygotować dokładne drzewo genealogiczne dla SS. Ojciec Alfreda umarł zaś zwolniony z obozu radzieckiego, gdzie przebywał jako volksdeutsch. „No tak, o tym też się w rodzinie nie mówiło” [s. 288] – notuje.

Wujek – lekarz obozowy

Budzyńska, dziennikarka i absolwentka kulturoznawstwa na Uniwersytecie im. Adama Mickiewicza w Poznaniu, wykonuje sumiennie pracę historyczki, tropiąc informacje o biografii wuja w archiwach polskich i niemieckich. Ma także bezcenny atut – pamiętnik Trzebinskiego, w którym oprócz faktów z życia zapisywał swoje ogólne refleksje. To kluczowe źródło towarzyszy nam w całej książce.

Wuj cztery lata po rozpoczęciu praktyki lekarskiej (studia zaczął we Wrocławiu, a skończył w Greifswaldzie, później praktykował w Mühlbergu nad Łabą) wstępuje we wrześniu 1932 roku do SS, otrzymując numer 133 574. Jego fascynacja nazizmem jest szczera, a wynika po części z wyznawania rasistowskiej eugeniki. W ostatni dzień 1936 roku Trzebinski oficjalnie występuje z Kościoła katolickiego, podążając za wskazaniami Himmlera.

Poznajemy kolejne rozdziały biografii Trzebinskiego. Karierę zaczyna w Auschwitz-Birkenau. Autorka szeroko opisuje obozy, w których pracował jej wuj, przybliżając zwłaszcza zasady funkcjonowania obozowych medyków oraz ich zbrodnicze zadania. Specjalista nie dowie się z tych fragmentów niczego nowego, ale są one niezbędne dla rekonstrukcji działań i postawy Trzebinskiego. Budzyńska zwraca przede wszystkim uwagę na niekompetencję i bezduszność obozowych lekarzy, punktowaną często przez lekarzy w pasiakach. W Auschwitz Trzebinski zetknął się z programem „eugenicznym” T4, a ściślej 14f13, polegającym na gazowaniu więźniów. Eskortował transport więźniów z obozu do Sonnenstein. Tam „być może po raz pierwszy miał okazję zobaczyć, jak wygląda taki proces masowego unicestwienia” [s. 111].

Następnie, późną jesienią 1941 roku, Trzebinskiego przeniesiono do obozu KL Lublin (Majdanek), gdzie został Lagerarztem. Obóz dopiero był rozbudowywany, dlatego początkowo pracy miał niewiele. Autorka stara się przybliżyć działania wuja, zrozumieć, na ile zbrodnicza obozowa rutyna była pochodną systemowych reguł, a na ile starań samego Trzebinskiego. Relacjonuje także wspomnienia więźniów, którzy mówili, że miał on „zupełnie poprawny stosunek” do polskich lekarzy, co przypisywali polskiemu pochodzeniu Trzebinskiego, które było im znane. „A jednak był renegatem” – dodawał jeden z nich.

Działalność Trzebinskiego przerwał tyfus. Wysłano go na urlop zdrowotny i rehabilitację do szpitala wojskowego położonego na przedmieściach Drezna. Przeżył tam załamanie psychiczne, które jednak nie zawróciło go z drogi zbrodni. Po przymusowej przerwie trafił do obozu Neuengamme. Awansowano go także na SS-Hauptsturmführera (odpowiednika kapitana). Kontynuując tam obowiązki lekarza obozowego, przyjmował nawet kobiety do obozowego puffu (domu publicznego). Budzyńska stara się wydobyć prawdę ze sprzecznych źródeł, w tym powojennych zeznań wuja, wedle których najczęściej nic nie wiedział o popełnianych w obozie zbrodniach (na przykład o egzekucji na sześćdziesięciu chorych Holendrach).

Wujek – morderca dzieci

Kulminacją opowieści jest opis zbrodni na dwudziestu dzieciach z obozu Neuengamme. Sprowadzono je do obozu późną jesienią 1944 roku na życzenie lekarza, Kurta Heissmeyera, który prowadził doświadczenia z prątkami gruźlicy. Pod koniec wojny, chcąc ukryć zbrodnie, wydano rozkaz zamordowania dzieci. Odwieziono je do Hamburga do podobozu Bullenhuser Damm, gdzie w piwnicy nieczynnej szkoły zostały uśpione i powieszone. Heissmeyer był nieudacznikiem, a jego badania były pozbawione naukowego znaczenia, ale miał mocne koneksje i marzył o profesurze. Trzebinski nie prowadził zbrodniczych badań na więźniach, ale jako lekarz obozowy pomagał na różne sposoby ustosunkowanemu doktorowi. Towarzyszył na przykład w sekcjach zamordowanych ofiar eksperymentów.

Dzieci były ukoronowaniem badań, miały posłużyć jako dowód skuteczności surowicy. Wybrano dzieci żydowskie, bo – według Heissmeyera – „nie było jakiejś szczególnej różnicy między zwierzętami doświadczalnymi a żydowskimi dziećmi” [s. 200]. Autorka prezentuje tyle informacji o najmłodszych ofiarach, ile udało się jej zebrać. W książce zreprodukowano także fotografie [s. 209–218], które wydobyto ze skrzynki zakopanej przez Heissmeyera. Na zdjęciach obnażone dzieci podnoszą ręce, pokazując powiększone węzły chłonne pod pachami i zaczerwienienie skóry w miejscach wtarcia prątków gruźlicy.

Powstaje tutaj wątpliwość, czy fotografie tego typu powinny być reprodukowane w nowo publikowanych książkach. Oczywiście, w sieci można znaleźć wiele zdjęć więźniów obozów i ofiar doświadczeń medycznych. Ale czy rozpowszechnianie tych fotografii nie jest formą ponawianego poniżenia osób, których ciała stały się przedmiotem eksperymentów i dowodami w bezdusznych sprawozdaniach medycznych? Niestety, Budzyńska w ogóle nie poddaje tej kwestii dyskusji. A przecież, jak podkreśla Susan Sontag w książce „Widok cudzego cierpienia”, nie wszystkie reakcje na takie obrazy „kontroluje rozum i sumienie”. Sontag stwierdza bezceremonialnie: „Większość obrazów umęczonych, okaleczonych ciał pobudza lubieżne zaciekawienie” [1]. Dlatego opisy wystarczyłyby, moim zdaniem, w zupełności, zwłaszcza w reportażu historycznym.

Budzyńska szczegółowo opisuje ostatnie chwile dzieci. Trzebinski podał im roztwór morfiny, aby oszczędzić im cierpienia – jak twierdził na późniejszym procesie. Następnie inny strażnik powiesił je. Jak później zeznawał (w opozycji do Trzebinskiego), część dzieci zmarła w wyniku zastrzyków, a część na skutek powieszenia. Sprawa ta była wnikliwie analizowana w trakcie procesu.

Pomijając wszystkie mniejsze i większe zbrodnie Trzebinskiego, był to jego ostateczny upadek. Cokolwiek mówił i pisał, brał udział w morderstwie najmłodszych ofiar eksperymentów medycznych. I jego wina jest bezsporna. Jak słusznie zauważyła autorka: „Ostatecznie jednak to zupełnie nie jest ważne, kto wydał rozkaz. Dzieci umarły, bo nikt nie miał odwagi się temu przeciwstawić” [s. 264]. W tym jej wujek.

Wujek – powieszony nazista

Ostatnia część książki poświęcona jest ucieczce Trzebinskiego z rodziną, próbom ułożenia sobie życia, aresztowaniu, procesowi i wykonaniu kary śmierci przez powieszenie. Autorka bez zmiłowania ukazuje moralną małość i bufonadę swego krewnego, który ciągle liczył na uniewinnienie i narzekał na ciężkie warunki aresztu. Porażające są zwłaszcza zapiski w pamiętniku, który przedstawia – jak stwierdza Budzyńska – „obraz człowieka, który nie ma sobie nic do zarzucenia, którego nie stać ani na moralną, ani na historyczną refleksję, na spojrzenie w głąb siebie, własnej duszy” [s. 283]. W innym miejscu autorka pisze: „Uspokoił się przekonaniem, że gdyby nie on, byłoby gorzej, dzieci umierałyby w męczarniach. Przewrotność biegu jego myśli poraża mnie” [s. 317].

Mimo jednoznacznego potępienia na kartach książki, Budzyńska przyznaje się do wątpliwości. Stara się zrozumieć, jak normalny człowiek, a nawet lekarz, który potrafił być troskliwy i bezinteresowny przed wojną, stał się nazistowskim mordercą. Sięga po naukowe wyjaśnienia Alberta Bandury, Roberta J. Liftona, Daniela Jonaha Goldhagena i Hannah Arendt. Poszukuje mechanizmów adaptacyjnych, które pozwalają wytłumaczyć „zawieszenie” moralności w obozach (takich jak „podwojenie” – doubling – Liftona). Tymczasem jej analiza biografii Trzebinskiego pokazuje siłę tych wyjaśnień, które zakładają, że nazistowscy zbrodniarze kierowali się swoiście rozumianą moralnością. Harald Welzer zauważył: „Relacja między masową zbrodnią a moralnością nie jest kontradyktoryjna, lecz ma charakter wzajemnego uwarunkowania. Bez moralności nie można byłoby dokonać masowej zbrodni” [2]. I właśnie kształtowanie moralności narodowosocjalistycznej dokumentuje autorka, pokazując system odniesienia w III Rzeszy, który podzielało wielu niewinnych we własnych oczach zbrodniarzy [3].

Trzebinski do końca nie wyszedł z roli. W notatkach dla córki udzielał jej porad, między innymi takich, że jako przedstawicielka „dobrej krwi” nie może dopuścić do siebie i swoich dzieci „złej krwi”. List ozdobił swastykami i runami. Miał też czelność w ostatnich słowach powiedzieć: „Panie, wybacz im, bo nie wiedzą, co czynią” [s. 356].

W książce znajdujemy wiele uwag na temat polityki pamięci, poświęcony jest jej także epilog. Szkoła, w której zamordowano dzieci, działała po wojnie normalnie, a z miejsca zbrodni zrobiono graciarnię (cóż za trafna metafora niemieckiej niepamięci!). Dopiero w 1963 roku umieszczono tablicę, a dziś znajduje się tam miejsce pamięci. Odwiedziła je także autorka: „Po raz pierwszy wystąpiłam nie w charakterze potomków ofiar, tylko potomka oprawcy” [s. 367].

Książka Natalii Budzyńskiej jest nie tylko świetnie napisanym reportażem historycznym, ale także pokazuje, jak długi jest cień II wojny światowej. Choć odchodzą ostatni świadkowie, to nie jest to karta zamknięta, ale historia żywa, która zmusza do ciągłych rachunków sumienia i rozpatrywania moralnych dylematów. Autorka nie tylko miała odwagę zajrzeć do rodzinnej szafy i wyciągnąć z niej trupa, lecz także przybliżyła nam wszystkim upiorną wielką historię, która od tamtego czasu skandalicznie często się powtarzała.

Przypisy:

[1] S. Sontag, „Widok cudzego cierpienia”, przeł. S. Magala, Wydawnictwo Karakter, Kraków 2010, s. 114.

[2] H. Welzer, „Sprawcy. Dlaczego zwykli ludzie dokonują masowych mordów”, współpraca Michael Christ, przeł. M. Kurkowska, Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar, Warszawa 2010, s. 42.

[3] S. Neitzel, H. Welzer, „Żołnierze. Protokoły walk, zabijania i umierania”, przekł. V. Grotowicz, Wydawnictwo Krytyki Politycznej, Warszawa 2014.

Książka:

Natalia Budzyńska, „Dzieci nie płakały. Historia mojego wuja Alfreda Trzebinskiego, lekarza SS”, wyd. Czarne, Wołowiec 2019.

Zawartość publikowanych artykułów i materiałów nie reprezentuje poglądów ani opinii Reunion’68,

ani też webmastera Blogu Reunion’68, chyba ze jest to wyraźnie zaznaczone.

Twoje uwagi, linki, własne artykuły lub wiadomości prześlij na adres:

webmaster@reunion68.com