Novelist Boualem Sansal Is Being Murdered by the Algerian Government

Novelist Boualem Sansal Is Being Murdered by the Algerian Government

Liel Leibovitz

Ask yourself why you’re not hearing about this story

.

© Iberfoto / Bridgeman Images

© Iberfoto / Bridgeman Images

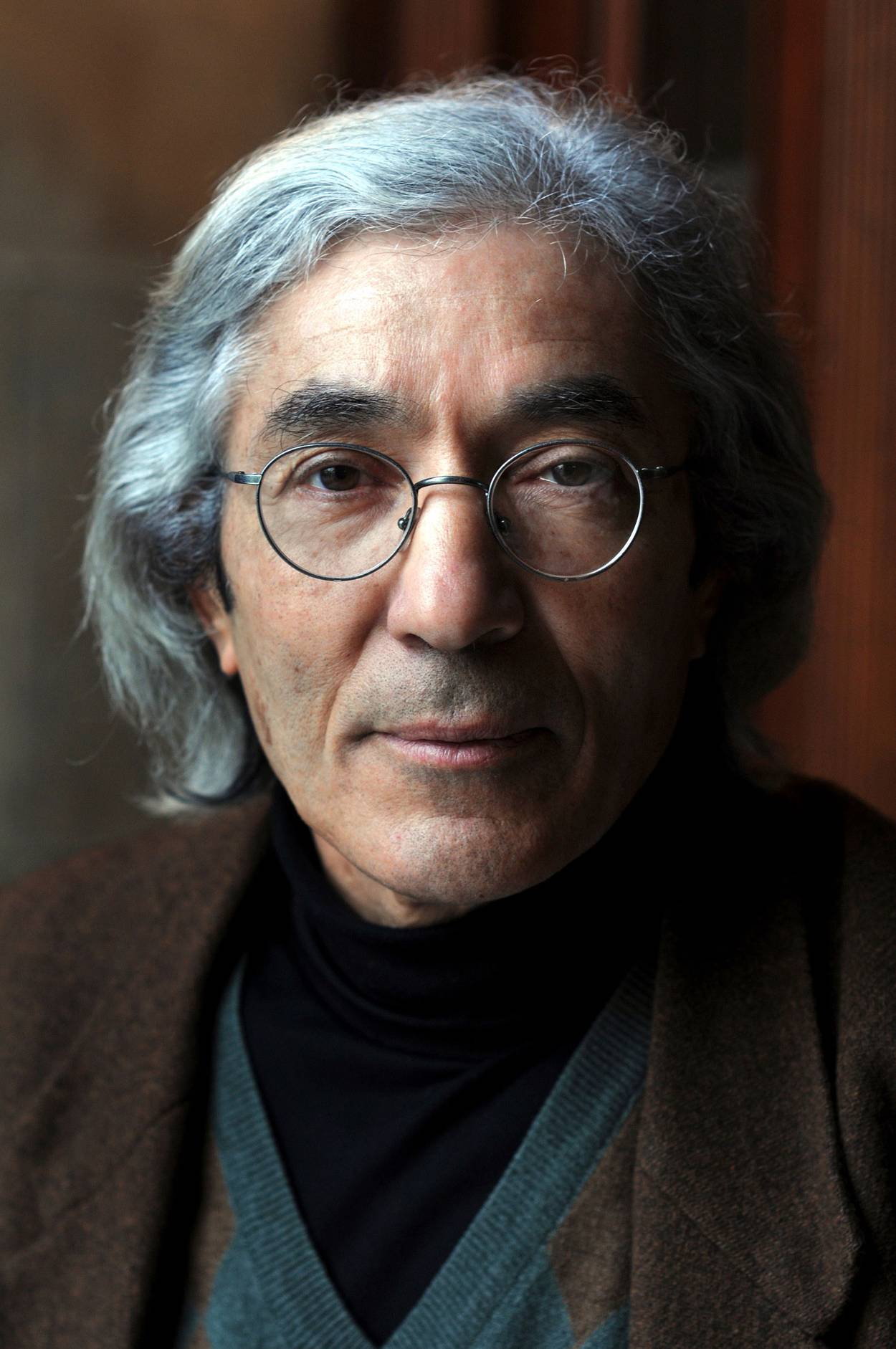

Boualem Sansal, one of France’s most acclaimed authors, disappeared on Nov. 16. For more than a week, his whereabouts were unknown. Finally, and under mounting pressure, the Algerian government admitted that it had seized Sansal and was holding him on charges of “endangering the nation.”

Sansal was born in Tissemsilt, in Algeria, and trained as an engineer. He also completed a Ph.D. in economics, and went to work for the Algerian government. He was a content and richly rewarded bureaucrat, working for the Algerian Ministry of Industry, but his homeland, he realized, was changing, falling under the sway of Islamism. And so, Sansal, by then a 50-year-old man with no previous literary experience, began to write.

His first novel, 1999’s Le Serment des barbares, was a hit, though it made some people uncomfortable. The book tells the story of an aged detective who investigates two murders and learns more than he bargained for about the corruption of Algerian society during the nation’s “Black Decade,” the bloody civil war that claimed as many as 150,000 lives between 1992 and 2002. It won a host of awards, and it made Sansal, who grew up right down the block from Albert Camus’ house, a celebrated French writer.

Which soon proved a problem. In 2003, after narrowly surviving the devastating earthquake that shattered Algeria, he published Dis-moi le paradis, a novel about a man who travels in postcolonial Algeria and witnesses the chaos, incompetence, and corruption of its first years as an independent nation. The tone was too candid for the government’s taste, and Sansal was forced to leave his position in the ministry.

Like all writers worth a damn, Sansal refused to cower and chose, instead, to fight.

Most authors would take the hint, and pursue more subtle stuff. Sansal went the other way. In 2008, for example, he published Le village de l’Allemand, translated into English as The German Mujahid. It tells the story—based on a real-life account—of a Nazi officer who flees to Algeria, helps the National Liberation Army violently kick out the French, and retires to a small village. When his children discover his secret identity, they have to wrestle not only with their lurid family lore but also with the question, virtually undiscussed before or since in the Arab world, of the affinity between Arab leaders and the Nazi party and ideology.

The work, advocating moral responsibility over tribal prejudice, infuriated many in his native country, but by then Sansal didn’t care. He was, he frequently said, a man exiled in his own homeland, committed first and foremost to telling the truth. So when an invitation came, in 2012, to attend Jerusalem’s Writers Festival, Sansal gladly accepted.

As a writer, he told the Israeli press at the time, he was sensitive to words and how they were used, and couldn’t stomach the thought that most Arab countries frowned upon people speaking freely about “Israel” or “the Jews,” a form of censorship, he added, that poisons minds and hearts.

“As soon as there is freedom of speech,” he said, “it will be possible to disagree with Israel if one wishes to do so—only without the hate. This is the reason I traveled to Israel and this is the reason I will return. We can argue about a certain Israeli policy, but the most important thing is to be friends.”

The same year, Sansal won a Editions Gallimard Arabic Novel prize, but the award’s sponsors, France’s Arab Ambassadors Council, revoked the 15,000 euros promised to the winner, arguing it could not reward anyone who had visited, and had nice things to say about, the Jewish state. The council’s decision, the director of France Culture radio later revealed, was influenced in large part by Hamas, which successfully lobbied the council’s members to punish Sansal.

“I wouldn’t wish Hamas upon my worst enemy,” Sansal said in response. “It is a terrorist movement of the worst kind. Hamas has taken Gazans hostage. It has taken Islam hostage.” And the Arabs, he added, had “shut themselves in a prison of intolerance.”

Some French intellectuals stood up for Sansal. Many others marked him as reactionary, someone who foolishly defied the “red-green alliance” that brought together radical Marxists on the one hand and fervent Islamists on the other under one trendy banner. When his next book, 2084, was published in 2016, it received mixed reviews. A riff on George Orwell’s famous dystopian novel, the book tells the tale of a postapocalyptic civilization governed by a fundamentalist cult that bears more than a passing resemblance to Salafism. And to many on the chic left, it was just another example of benighted boobs hating on the religion of peace.

“In twenty years, when the Islamophobic waters of France have ebbed, we will wonder how we could have gotten so excited about such a slow thriller,” wrote the editor at the time of the magazine Paris Match, adding that “fear is an excellent appeal” and that Sansal was merely exaggerating the threat Islam posed to the Western world.

Earlier this year, Sansal, feeling that his own safety in Algeria could no longer be guaranteed, became a French citizen. President Macron attended the ceremony. And yet, the writer refused calls to stay away from his native land. Like all writers worth a damn, he refused to cower and chose, instead, to fight.

And now he’s in custody, held by an authoritarian regime and accused of imaginary crimes. And while some of the literary world’s braver souls are standing up and demanding his release—a tip of the hat, as always, to the brave Salman Rushdie—most of our bien-pensants are silent. The same mediocrities who collected awards while squawking about the fictitious genocide in Gaza are once again siding with the marauders, betraying a far greater writer seized for the sin of adhering to humanism’s core commitments.

Every reader must demand the immediate release of Boualem Sansal, or, at least, the complete ostracization of the Algerian government until he is freed. And until Sansal is back home with his loved ones, the least we could do is show our respect to his courage and his values, the values of Western civilization, by spending the days he languishes behind bars reading his books and praying for his safe return.

Zawartość publikowanych artykułów i materiałów nie reprezentuje poglądów ani opinii Reunion’68,

ani też webmastera Blogu Reunion’68, chyba ze jest to wyraźnie zaznaczone.

Twoje uwagi, linki, własne artykuły lub wiadomości prześlij na adres:

webmaster@reunion68.com